Sydney Pollack with Nicole Kidman on set of The Interpreter

The armature of The Interpreter

Anthony Minghella: Thanks all of you. It’s a great honour to be here as the chairman of the BFI, but also this is my day job colliding with my night job. It’s a real privilege that we have here tonight my partner, my friend and a great director, Sydney Pollack. [applause]

Sydney Pollack: Thank you.

AM: It’s quite hard to do this and pretend that I don’t know anything about this film, which I’ve seen about 150 times. But it’s really interesting to watch it with an audience in London and it makes you think because you know you’re going to have to ask some questions at the end of it. And so I spent the film thinking about Sydney, and thinking about the way he makes films and the number of films he’s made and the career he’s had. And this film has so many of the elements of the movies that you’ve made over the years, in very specific ways.

And we once had this kind of conversation at BAFTA — a really wonderful evening where you were on sparkling form — and I remember something that emerged from that, which I’ve never forgotten, where you talked about how in a film what you look for is an armature, some kind of piece of wire that’s in the centre of the film that holds everything together. And I was thinking during the watching of this movie what you would describe as the armature of The Interpreter.

SP: Well, first of all it’s an armature that you helped me find. So you probably know it better than I do. I think it developed as we went along. I get a little lost if I don’t have it. It’s not ever something that I think should be blatantly visible but it’s the thing that helps me work on a film, that is if I can say to myself this is a film that says, or is about, or is preoccupied with, and I can answer that question in a phrase that I can turn into behaviour or sequences then it’s an enormous help to me.

It doesn’t ever help if it remains intellectual – and it always starts intellectually – so I guess the first statement of it was it’s a film about diplomacy versus violence. But that’s not dramatisable, as far as I know, as an idea until it moves beyond that to something else that I can start to stage in some way. So then I kept on playing with that and that became… it’s called The Interpreter so we know it has to have something to do with words. And words are a great instrument of diplomacy in a way. So then it became a question in my mind… if words are a primary instrument of diplomacy and diplomacy is a primary alternative to violence, then do words have to have the same power as bullets do? Or knives or something like that? And can they?

I did a lot of rereading of the real thing… of Tom Stoppard’s play. And I got very hung up on the section where the playwright does a kind of lecture about the cricket bat, about words and about how, when they’re used properly, how powerful they can be. And he says he’s not defending writers but he is defending words — the playwright says. And so when I worked with the writers, I kept thinking about this particular speech. And I kept trying to figure out whether words in some way… and that really ultimately is what led to the final dedication of the book that she forces him to read about himself.

There were a lot of steps along the way as Anthony… Anthony was holding my hand through all this and also writing through all this… there are lots of his lines in this movie. But a lot of this was in steps and we arrived at this idea that somehow this was a guy who started as a good man and has to face what he once was as a good man and the way that we finally ended up doing it was for him to face the words he chose to write — which was about words, and about how powerful they can be even as the whisper against the sound of guns if they do tell the truth. And that kept on evolving in some way, and Anthony and I had lots of talks about this.

I think he might not buy what I’m going to say now — we’ll see — but it sort of evolved into – for me – a film about a healing, about forgiveness… about healing because you can’t get over grief and you can’t get over the wish for revenge without some kind of wound getting healed. And so the question is: what do you have? You have first aid, you have alcohol, you have this, you have that, or you have getting even. That’s what people try. And all that does is continue to prolong the injustice chain so to speak. So this became a question of — for me — of how do you get past all of this?

I’m making this all much too much complicated because he asked me this complicated question. It’s really a thriller, you know, you’re just supposed to have fun. [laughter] So don’t get as hung up as I’m getting on all these explanations. But that’s the process for me as I have to think like this in order to do the bus sequence which is just about… are they going to get on the bus or are they going to get off the bus… that’s really finally what the movie’s about. But you still spend all of this time thinking all these pretentious things and then trying to hide the pretentiousness of it, basically.

But it became about healing in the sense that it started with somebody saying ‘we don’t say the names of the dead.’ And my wanting very much, just in terms of my feeling about form, to end the picture with her saying ‘what was your wife’s name?’ And then I had a hell of a bad time trying to get there. And Anthony helped me by just beating me up over the inconsistency of the thought, well, you’re not supposed to say the names of the dead, how the hell can you get to this point where she, the heroine, says ‘what was her name?’

So I turned myself into a pretzel and the picture into a pretzel in a way trying to justify this as a first step in healing. Trying to say ‘you move on.’ She says you have a choice with the drowning man: you can have your sense of revenge… it’s not going to get rid of your grief. What it will do is give you a sense of justice but no sense of the relief of grief. So anyway, I got hung up in all that stuff.

Sean Penn in The Interpreter (2005)

Language and writers

AM: You can see how the process of making the film went really. And one of the things I wish that — as Sydney is talking — I wish that I could have played back some of the conversations that we’ve had over the last year and a half or two years. Most of them at about three o’clock in the morning my time in London because unfortunately Los Angeles rules OK and so…

And what’s interesting, I think… two things, I think, one of them is that all I thought about during this film was words. Because more than any other filmmaker, I think, working… and it’s odd because you always say ‘I’m not a writer, I’m not a writer, I’m not a writer,’ but language and words pop through this film. You hear every line and you have to think about every line and you enjoy language as a director, and your actors enjoy language in a way that I think almost no other director feels comfortable allowing so much air and love around individual lines… these sort of ethno-grammatic lines. And so you actually start to think about language, you test us, you make us remember language… ‘dead, not gone, gone not dead.’ You make the audience start to have their ears cleaned out all the way through the film.

But one of the things that interests me is that because I’m a writer, and so when I go to work I write a script and then I direct it. I mean obviously it goes through your fine mesh of criticism and assault, but basically I make the film that I write. What’s fantastic and fascinating and extraordinary is seeing Sydney working with writers because the director, finally, is the author of the film, I think. I think that’s very clear. But if you’re not somebody who has ink in their pen or trusts the ink in their pen then you have to somehow channel your idea of this film through other writers.

And one of the most extraordinary things for me was sitting in New York in Sydney’s apartment or in Los Angeles in his office, working with writers and seeing this person trying… it’s almost like somebody who’s not a dancer trying to make a ballerina move. Because I was one of those writers trying hard to write a scene that you might like one word of. [laughter] And this nose sniffing out a half decent line and throwing pages… and lots of actually fairly good writers at work… Steve Zaillian, an amazing writer… a lot of great writers involved… Scott Frank… all of them become the genuflecting acolytes around you, trying to make one line or two lines that suit you. It’s a very interesting process to see how you have this steely grip on the way that the film evolves, don’t you?

SP: Well, I don’t… I’m not a writer myself so I’m forced to try to get what’s a sort of an odour or a colour or something I feel in my head from a writer and that’s a… I don’t have a recipe for that process. I don’t know what it is… it’s different every time. So it’s a sort of a tortuous process, I’m sure it’s much more tortuous for the writers. But it’s somehow trying to get something that I can sense from somebody else and it’s a little… It’s like sculpting in a way… you get half of it, or a piece of it, you get almost there and then you just keep going and keep going… and I know it drives writers crazy… I mean it just literally drives them crazy.

AM: What’s interesting in the film is actually as you said the end when Zuwanie’s preface… I’m trying to think of what other director working now would, at the end of a thriller, have the central character read a preface of a book… or the fact that in a key emotional moment, Nicole is reading words from the notebooks of her brother… that language plays such a key part in the way that this film has evolved. And it always has. I mean when you talk about the films that you make, you always remember… there’s a wonderful uncredited writer always who works with Sydney called David Rayfiel who… seeing the two of them together because they go back how many years?

SP: 40.

AM: 40 years of writing where in a way it’s like a marriage, isn’t it?

SP: Yes, very much so. Very much so.

AM: So poor David, who’s a wonderful guy who writes a line and hands it over to Sydney and Sydney says ‘what is that, David? What is that?’ Then occasionally some beautiful like… when Sean says to Nicole ‘what do you think about Zuwanie?’ and she says ‘I’m disappointed.’ And he says ‘that’s a lover’s word.’ That… Sydney called me and said ‘listen to this, listen to this, listen to this. It’s a David scene, it doesn’t work. Listen to this line, do you love that?’ And it’s like this thing of trying out the lines until there’s one that sticks… and you could run your thumb across this film and there are so many of these moments which for actors are wonderful things to play as well.

SP: Yes, but oddly enough — and it’s true, David’s been writing with me… we’ve been writing together since the early 60s really — in television, we started in television. And he’s written on every film I’ve ever done except, I think, one. Yes, one. I can only think of one film that he didn’t…

AM: That’s 155 films.

SP [laughter]: That’s right. But only one that he didn’t write on. He’s a sort of an amazing guy who has this poetic ear, as you know. And it’s a process he loves and I love too. We’ve been doing it forever and ever and ever and ever. He has a way of getting under the reality and making some kind of oddball connection with things. We have… there’s a line in the… it’s not nearly as interesting as ‘that’s a lover’s word,’ but Sean says to her ‘you think not getting caught in a lie is the same thing as telling the truth.’ And that’s the fourth movie that that’s been in. [laughter]

I’m terribly embarrassed. And I get caught all the time. Some journalist will come and say, ‘now I count three movies, is that right or is that…’ It was in the first movie I ever did, which was the first time he wrote it, in 1965; it was in a movie… Redford said it to Natalie Wood in This Property Is Condemned in 1966; Redford said it to Cliff Robertson in 1975 in Three Days of the Condor; and Sean says it to her here.

And somebody told me… a journalist told me ‘I knew that the Los Angeles museum of arts called LACMA — or whatever — has done a film series the last two weeks called Paranoia Films of the ’70s . And they showed The Parallax View [Alan J. Pakula, 1974] and All the President’s Men [Alan J. Pakula, 1976] and all these 70s films and they showed Three Days of the Condor. I wasn’t there but it was a good new print or something. And they said, when Redford turned to the CIA guy and said ‘you think that not getting caught in a lie is the same thing as telling the truth’ that the audience applauded. [laughter] I think it has to do with the political climate in the States right now — really. But to them it read like a brand new line, apropos of today — and this is 197…, it’s 30 years ago. But he’s that kind of a writer. He does write these memorable things.

Nicole Kidman in The Interpreter (2005)

A man and a woman

AM: One thing that’s really interesting is that that soliloquy you gave at the beginning of this, when I was talking to you about armature and you spoke so eloquently about it, I think also goes towards the heart of the kind of films that you make. Because you said jokily about two thirds of the way through, actually it’s just about a bus sequence. And I think that’s one of the tensions that’s running through this film and almost every film you make is that one part of you is this super creator… choreographer of action. It’s so effortless.

If you’re a filmmaker and you look at this film, it’s so annoying how effortlessly the bus sequence is shot and edited and put together and how experienced you are at knowing how much you have to measure out, how long you stay in a sequence, the end sequence. It’s just so efficiently, beautifully produced and achieved. And yet, I know that for you, you talked about if we were measuring what we spoke about that was probably about a hundredth of our time and energy in the preparation with worrying about how to shoot the bus sequence which keeps the whole audience on the edge of itself.

And all you seem to worry and worry and worry and worry over is what a man says to a woman and what a woman says to a man. And if you were to break this film down into music, it has these very electrifying, sizzling sequences of action. And then these extremely legato connections between a man and a woman. And that conversation between that man and a woman has been a conversation that a man and a woman has been having for 25, 30 years in your films. What is that conversation?

SP: Trying to figure out how to make it work, I think. I mean I think there are only two things in the world that — really — that we have made no progress in whatsoever. One of them is men and women and the other is violence — honestly. We progress by leaps and bounds technologically, medically — we can live longer, we can… but you know, in the year 1230, they knew as much as we know now about the human heart.

80-year-old men today will scratch their head and say ‘I tried it a couple of times, it didn’t work. I don’t know what the hell happened or whatever. I can’t figure out women.’ Whatever anybody will say, we… it hasn’t gotten to where we’ve said ‘we’ve got it figured out now. Here’s what it is. Here’s where it’s been going wrong. Here’s why there’s all this frustration. Here’s why it seems to work and then it doesn’t seem to work. Here’s why there’s so much yearning. Here’s why people are lonely. Here’s what it is – they got it wrong.’

We thought it was… you know… vitamin C, but it’s not, it’s vitamin E, we figured this out in everything except we’re exactly the same in terms of destroying each other and we’re exactly the same in terms of our wish to achieve something that seems so elusive in terms of two people. Not that it doesn’t ever work, I don’t say that for one moment. But that it seems so rare that is works and seems so often sought after. So… I’d get bored if I… if I had to do a movie and there was no love story in it I would just be bored. I mean I would do it but it would be kind of boring.

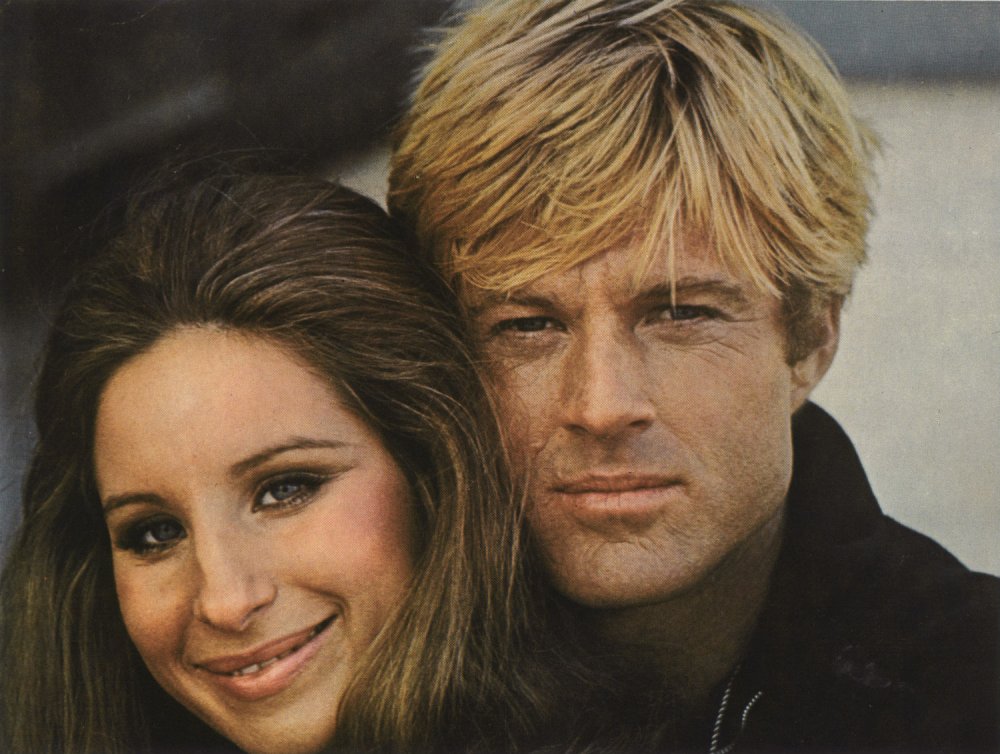

AM: But your love stories… I mean you must know… all of you who have watched The Way We Were [1973] or Three Days of the Condor, Out of Africa [1985], all those movies… you then start talking about these two… this man and this woman who are… who never quite connect. I mean that scene at the end… we’ve talked about this, how many times in one of your films… I mean in a way you wrote the model of that scene at the end of The Way We Were with Barbra Streisand and Redford as Hubbell and Katie… that’s sort of in everybody’s… I think everybody who’s ever written a film fights that last scene, fights having to write that scene… but there’s a very… they could walk from film to film, that man and that woman in some way…

SP: Yes.

AM: And they are… it’s interesting that you say that ‘disappointment, that’s a lover’s word’ because they are disappointed, aren’t they?

AP: Yes, yes they are. Constantly disappointed. It’s like… I always think of somebody I read early, when I was a kid… that Giacometti, the sculptor Giacometti said ‘I sculpt because I’m curious to know why it is that I fail.’ So he kept on working for that reason. And there’s a certain amount of that mentality… I think that I… that’s in me in some way about everything in a way. That you just keep wondering what is the reason that it doesn’t work better… men and women or human beings… those questions are what make the film interesting to me.

I always love the idea of the discipline of a Western or a thriller or a comedy or whatever… that’s the filmmaking part… that’s the kind of… and that always… I love it when I get to that because that has an answer. That’s finite. I figure if I work long enough, I can do the bus scene. I can figure it out. But it’s not rocket science. It’s just mathematics. The other part isn’t.

The other part scares me to death because I don’t know the answer to the other part. So that’s the part I love to wander into. It’s like the unknown territory. Except I keep going back over the same stuff again. But that’s the heart of the filmmaking for me. I love… I have great fun with… and the irony, of course, is the only thing the audience really cares about is the bus sequence… Well, you know what I mean, that’s what makes the film work or not work on a massive… on a large scale level, not on a small level. And that’s the part that I feel pretty comfortable with… I don’t always but… whereas I get really hung up on the other part.

As you said we spent… like you said one is a hundred and one is five. How much talk did we do on the bus sequence? Almost nothing. I mean the trick, believe it or not – if you want to talk about technical problems – is that the first time the bus sequence got written, nobody was on the bus. Nobody we cared about was on the bus. Nicole wasn’t on the bus. And Sean wasn’t on the bus. Nobody was on the bus.

So we were doing this great bus sequence and so I drove… I said to Scott Frank who wrote the bus sequence, he came, I said ‘what is this?’ ‘Well, you know, we got this bomber, why… we got to use… if he’s going to… we got a bomber, he might as well do a bomb, you know.’ I said ‘yeah, but there’s nobody in the movie on the bus. You can’t do this.’ ‘Well, how are we going to put… how the hell are we going to get somebody on the bus.’ ‘I don’t know but that’s the job.’

So we spent four months trying to figure out how the hell to get her on the bus. Never mind why she’s on the bus. How the hell does she know where the bus is? Or what time the bus is? Or what is she… a psychic? She just shows up there on the corner. It was hilarious. Trying to just figure out this one problem… she reads a newspaper and it says the bus takes off at 10.30. That’s pretty obvious. What, let her open a newspaper and it says the guy takes a bus every morning at 10.30 from the corner of Nostrand and Bergen . And that was the answer to that but it was three months ‘til we came up with it, you know. [laughter]

Barbra Streisand and Robert Redford in The Way We Were (1973)

The actor as director

AM: The interesting thing is, I think, as a partnership, I’m so much somebody who wants to be an optimist about everything. But somebody once said the definition of an optimist is somebody who lives with a pessimist. And working with Sydney… everyday I’d call him and say ‘how’s the movie going?’ ‘Terrible. Terrible. What’s the point? There’s not one line, nothing works, there’s no scene in this movie, why am I doing this movie? I hate this movie. I hate myself. I’ve always hated my… I hate directing. I hate making films. I hate going to work. I hate everything. Have you read this new scene? Nothing works. There’s not one moment…’ And it’s the sort of process of such attrition, but also this sense, too, that everything is technical, that everything does yield, finally, to working at it. And I think there’s a real sense of working your way to a result in a film, isn’t there for you?

SP: Well I do believe… you and I have talked about this a lot that everything is, finally, disappointingly, it is technical. Every time I work with someone – I’m not talking about working with a writer – but I’m talking about people that are trying to help… they’ll read a script and they’ll say things like ‘well, that scene has to be more proactive.’ [laughter] Or ‘that scene has to be deeper.’ I want to get a weapon and do really hard physical damage to those people. Or ‘that scene needs deepening and needs more complexity.’ And they think they’re helping. And it’s just that you have to find a precise technical way to achieve everything that you’re doing, as you know better than anybody. And it’s so hard to do that when you’re constructing… it’s hard to do it when you’re shooting, too, but particularly hard in the construction of a script. And I would like to tell you that he’s exaggerating a bit with me… I’m not quite that depressed… and I don’t think of myself…

AM: You’d be lying though…

SP: Yeah well… I do spend a lot of time looking for what the problem is rather than looking at what’s accomplished… I keep looking at what isn’t accomplished… it’s my way of goading myself into working. Anthony’s flown with me a lot… I fly an aeroplane and I think a lot about how much I do not want ever to run into an optimistic air traffic controller. I just don’t. I want a guy down there who’s just waiting for the worst crash possible and petrified that it’s going to happen on his watch. And then I feel safe flying into his territory.

And directing a picture, to me, is every bit as risky as flying an aeroplane – riskier. And so I attack it in the same way. I keep saying ‘okay, I’m going to fly over the ocean now, with nowhere to land. I’ve gotta make sure the engines are running perfect, that I’ve got enough fuel, that I know the route, that I’ve got all the charts and if this goes wrong I’ve got another chart I can get here and if I do loose an engine I can get to Iceland or I can get to here, I can get somewhere… it’s just a way of work for me. Partially because I don’t write, partially because I can’t take care of myself in that way that you can where you can write it and direct it.

AM: I think that everybody who saw the movie in here tonight will be aware of just going back to a look of New York which we haven’t seen for such a long… the film looks so beautiful and the UN — I think you’ve talked in many places about that, but one thing I think would be worth, before we open ourselves up to some questions from the audience, is to talk a little bit about the fact that you’re an actor, you’re an actor in this film and that’s always such a pleasure to see you as an actor, but it also makes me think constantly about how that sense of your own skill as an actor conveys itself and is useful to you as a director of actors. How does that work exactly?

SP: Well, most of the best directors that I know are not actors so I don’t think it’s in any way a requisite. For me, it’s the only thing I had when I started. Because I didn’t begin thinking about directing ever… I mean I never even imagined what it would be like to be a director. As far as I went was to say could I make a living as an actor or something.

The thing that I brought in to the directing in the beginning, or the only thing I had when I started directing was whatever technique I had learned in a way of attacking a role. And that’s where the armature came from. I was always saying in the role, ‘what’s this scene about? What’s the play about? Who am I? What do I want? Why do I want it? What’s my specific relationship to the other actor?’ Whatever… those actor’s questions became the foundation of directing for me and in some way I direct everything like an actor. I try to do that as much as I can, even with the cinematography, if you will, in a way. Certainly with the characters talking to the actors, the clothes, the sets and all of that, how much can I tell you about a character by the room that they live in or the clothes that they wear, or what’s hanging on the walls or what’s in the drawers or things like that.

That grew into a directing technique for me but it started and began with the acting. And I always think of… every time I get into an intellectual situation where I’m discussing with the studio head or someone… the producer, let’s say – I very rarely work with another producer other than myself or Anthony because I produced most of my own pictures early on – but occasionally I have another producer and will talk, or the studio will sit and have notes and whenever they talk I remember old acting classes with my acting teacher where he would say ‘what is this scene about?’ to the actor and the actor would say ‘well this scene is about the fact that I need money to go to see my dying mother’ and then Meisner would say ‘well let me see you act that you need money to go. Let me see you act that.’ And they didn’t know what to do. Because you can’t act it. So he’d keep asking until you got the point that you can’t act… that’s an intellectual… that doesn’t have anything to do with behaviour. And he would slowly show you that until you say something that’s behavioural you haven’t helped yourself in any way. And that’s, for me, the basis of the directing technique that I use. So that it all comes from that.

AM: And the writing technique.

SP: Yes. And the writing technique. I mean everything came from the lessons I learned as an actor… until he pushed them into saying something that was immediately do-able in terms of behaviour. He used to say my aunt Alice can tell you that the scene is about getting money to go to see your dying father. It’s got nothing to do with acting. That has nothing to do with the scene. That’s just facts. What is the scene about? And he would keep on until you got to a point where you said… ‘this is a scene where I have to do the thing that I hate most in the world. I’ve got to confront… it embarrasses me so badly to ask this guy for this money that I need to go see… because… I hate… I can’t stand what I have to do…’ or something where you can… where it’s behaviour right away. And then it becomes that. And that’s sort of what the writing process is for me and also what the directing process is.

AM: Well, my worry is that one day the couple in your films will say ‘you know what, we love each other, we’re happy together, let’s just go off together’ and you might figure that you’d stop making movies… I hope you never do.

Sydney Pollack on set of The Interpreter (2005)

Questions from the audience

AM: And I think it would be fun just to take a few questions now from the audience. Are we going to have microphones or are we going to bellow at each other?

SP: Just bellow.

AM: Yes, bellow. Bellowing’s good I think.

Audience member: [inaudible…]

SP: Well that’s not bellowing.

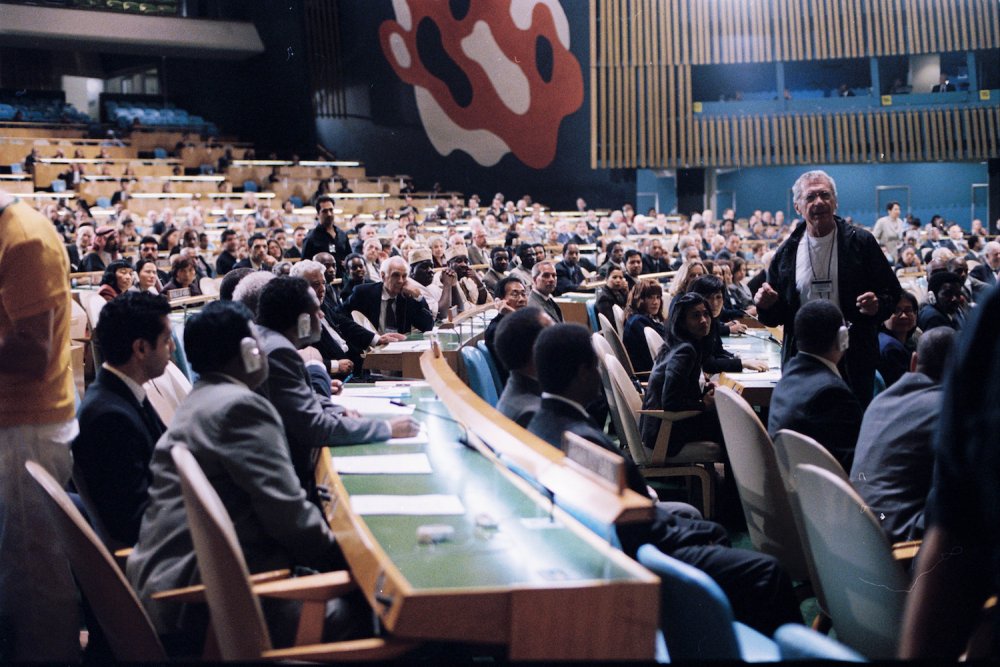

Audience member: How long did it take to get permission from the UN to film in the UN headquarters?

SP: How long did it take to get permission? It was really not a question so much of that as much as it was a question of getting to Kofi Annan. That was harder than getting permission. The problem was how to get to the boss. You know, the standard bureaucratic answer was ‘no’ and that’s what we got several times. But because we… because nobody had bothered to go up the ladder we just accepted the ‘no’ and I accepted it too like a dummy and we did all this preparation in Toronto for what they call CGI or computer graphics work and finally it just got so depressing, the whole idea of trying to pretend that you’re in the UN when you’re in a corner of Toronto or something silly. [laughter]

So I went back to New York and started making phone calls to see if there was anybody in the world I could find who could get me to Kofi Annan. And I have a very good friend who’s an investment banker. He knew of my plight and he called one day and said ‘I’ve got Bob Kerry here in the office.’ Bob Kerry is an ex-senator United States who was a part of the 9/11 Commission. He’s a great guy – he’s the head of the new school right now in New York, new school for social resources – and anyway, he said ‘I’ve got Bob Kerry here, he could get you an appointment with Kofi Annan.’ And Bob Kerry got on the phone and said ‘I’ll get you an appointment with Kofi Annan.’ That was the big hurdle. Then I went to see Kofi Annan and he took a few weeks to think and we finally got permission.

AM: Yes.

Audience member: Thank you very much for a very well-done movie and [inaudible…] And I got thinking, why does the senior… the main character always have to be a white woman and it’s a movie about Africa? [laughter]

SP: Well, because it was from a book that we bought that was written by a real woman who was white. She was Danish, her name was Isak Dinesen. Karen Blixen – actually a famous woman – and it’s a famous book… I couldn’t really change her to a black woman. She wasn’t a black woman, she was a white woman who went to Africa, who did all of what you see in the picture, what was in that picture.

And it’s a project that floated around… actually she wrote it in the 30s and it was around Hollywood from the 30s on and everybody wanted to make the picture. It was a lovely, lovely memoir of this white woman’s time in Africa… that was the whole point of the book. It was about a white woman who didn’t belong there who went there from this white snowy country of Scandinavia and the problem that other directors had was that the book was very poetic and didn’t have much story in it.

I knew about the book for 20 years and the advantage I had was that a wonderful woman named Judith Thurman happened to write the biography of this woman Isak Dinesen — it won the National Book Award — right at the time when I was trying to make it, and her book told all of the facts that became the story. About the syphilis and about her marrying the wrong brother and about her husband’s infidelities and her real love for Denys Finchatten . And Finchatten ‘s death. These were all… every one of these characters was real. They all lived. And there are books about all of them. There’s a book about Denys Finchatten called Silence Will Speak, a very famous book. There’s a book called West with the Night which was about the young girl that was in the picture called Felicity. They’re all true, everybody’s true.

Audience member: So when are we going to see one who’s African, the main character’s African… they’re out there.

AM: We’re doing… Mirage, our company, is going to make a series of films based on The Number One Ladies’ Detective Agencywhich has an entirely black cast.

SP: We’re doing that now. We’re trying to do that now.

Audience member: I was just wondering how… what is your process that your actors… [inaudible…]

SP: It’s different in every picture and it’s different with every actor and it depends on whether there’s a completed script and we have time to read it and prepare it in that way or whether we don’t. In general, the short answer would be that I tend, probably, to be less of a rehearser and more of somebody who likes to shoot before everybody’s too settled in and too prepared. But I do like to talk a lot with the actors and talk about the part. I don’t like to rehearse a lot. For me, just for me… I don’t mean that this is right or wrong because I see great movies where there’s a lot of rehearsal.

I think rehearsal for me is a theatre process and I don’t particularly like it a lot in movies. Because there’s never performance in a movie, because there’s never anything but rehearsal in a movie. There is no equivalent to a curtain going up in a movie. It doesn’t exist. It can’t. Because you can always say ‘let’s do it again.’ That being the case, there is no… you’re never doing anything in a movie except rehearsing. And you make the film in the editing room then.

So I don’t… for me it would be an anathema to set and lock the way you would a play and then record what you’ve set and locked. Now I’ve seen great movies made that way but I couldn’t possibly do that. It just doesn’t work for me because it’s such a weird process. A movie is just a weird thing since there’s never a performance. Never. It’s never the real time… okay tonight, good luck everybody… five minutes, half hour, let’s go. There’s no such thing. It never comes.

AM: Well you also said something to me once about that which is that you only need, as a director, to have an actor achieve something once. Whereas an actor in a play has to try and organise a performance so that they can repeat it every night and phrase it over the whole evening. Directors are very… actually they’re criminals aren’t they because they just steal good bits of everything and so…

SP: Exactly.

AM: …in a performance you just can… and sometimes the stealing goes on from the wrong scene, with the wrong lights, with the wrong continuity because it’s a moment that you need in the scene. And that’s just the fact of the matter isn’t it?

SP: That’s right. That’s right.

AM: We should have one more question I think from the gentleman at the back here, with the white shirt.

Audience member: As an accomplished director, how do you find your experience acting for Stanley Kubrick in Eyes Wide Shut [1999]?

SP: Well, one of the reasons I enjoy working occasionally as an actor is not my great love for acting anymore – I’ve given that up a long time ago – it’s more to spy on directors. I mean, you know directors are terrifically territorial. They go and pee on the corners of the stage so that nobody will intrude on their territory. And directors don’t let other directors on the set, they don’t… actors get this advantage of seeing other actors and other directors.

So the opportunity to watch Stanley Kubrick work was irresistible to me. Or watching Woody Allen… it’s part of the reason that I do it. I don’t know how to describe him. He was a really unique, one-of-a-kind guy. In my experience, the word ‘perfectionist’ has always in my business been a euphemism for ‘pain in the ass’. Anybody that makes enough trouble gets labelled a perfectionist. Always. Actor, director, whatever.

The only real perfectionist I ever met in my life was Kubrick, where there was no limit, literally no limit to the lengths he went until he was satisfied. With no sense of anything other than the ability to continue until he’d got what he wanted. And he would always say… whenever the poor woman who was the production lady would say ‘Stanley, how long… much longer do you think this will take?’ after we were two weeks over and five weeks over and two months over and three months over, he would say ‘it takes as long it takes.’ That’s all he would say. It’ll take as long as it’ll take. And he believed that and he didn’t budge. He was literally intransigent. You couldn’t budge him.

Now I personally found it unbearable. I couldn’t stand it. I mean I wanted to escape. I wanted to run away. On take 80 or 90 I was going crazy. But I was fascinated. He just kept going. Now he didn’t — in all fairness — he didn’t do it on my angles because he knew better. I couldn’t do any more. I’m not a professional actor. I just said ‘come on Stanley, nothing’s going to happen… you keep doing this.’ So he said ‘okay’.

But with Tom Cruise – and I had to be in the scenes with him – by take 100 I was punchy and so was Tom. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing anymore. Stanley would go ‘mmm… mmm… Come here.’ He would sit down and he would play the scene and he would say… and he would freeze the scene. He would say ‘now see when you reach there, you see how you hesitated with the glass? Don’t hesitate. Just do that. Okay? One more please.’ And this would go on for weeks — weeks! I mean you thought you were in a nightmare. You thought you’d taken some kind of drug. I’m hallucinating that I’m making a movie with Stanley Kubrick.

But he was a genius. He was a brilliant, brilliant man to talk with. He was the most generous guy in the world. He loved to get on the telephone and talk about your problems. You know I got hung up on… I was making films and I would talk to him. I knew him for a long time. I didn’t meet him personally but I used to talk to him on the phone a lot and I used to get into these long conversations about my problems, you know. ‘Wow, I’ve got this third act problem…’ and he would get really genuinely interested. ‘Well, did you try this?’ ‘No, I didn’t try…’ ‘Well, did you try… well what about… why don’t you call so-and-so and ask him to…’ You know he’d really get interested in it. Then he would call two days later and say ‘did you figure that out? Did you figure the problem out?’

He was a great guy. I miss him from that point of view. I never hung up from a phone call… there were lots… he loved to talk and there were… sometimes you’d be on the phone for two hours with him. I never hung up with him, honestly, where I didn’t feel better than when I started talking with him. He was one of those guys. Really interesting man.

AM: Well I can safely say I’ve never hung up from Sydney not feeling better than when I started. [laughter] And also what a shame it is there’s only been one comedy in this run of films because you can see what an entertainer you are and I hope we find another one for you to do.

SP: Me too.

AM: And thanks very much indeed for coming.

SP: Thanks for being here.

[applause]

Interview © BFI 2005