Web exclusive

The Immigrant (2013)

For fun and to risk a certain degree of humiliation the first part of this post is written in ignorance of which films have won the Cannes prizes. Part two will comment of the jury’s actual choices.

If you ask me now what will win the Palme d’Or I will answer that I haven’t the faintest idea, for there’s no single standout that fits the frame. A lot of optimists think they saw it with Abdellatif Kechiche’s history of a lesbian passion Blue is the Warmest Colour. Some gossips report that the jury was devastated by Asghar Farhadi’s marriage breakup switcheroo The Past. One sharp cynic gave Mahamat-Saleh Haroun’s portrait of a desperate man Grigris the best chance on the cynical presumption that jury president Steven Spielberg might be enthused to have found there is such a thing as African cinema; others assume that because Kore-eda’s Like Father, Like Son is so family-oriented and sentimental a saga it will win.

But if I use the word ‘favourites’ here I will be referring to the films that most impressed me, rather than likely to have impressed the jury, and that’s a hostage to the very good fortune that this year’s Cannes has enjoyed in its choices. Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty, the Coens’ Inside Llewyn Davis and the Kechiche are the three that I rate most highly, but I have no confidence in any of them actually winning. I can’t see Spielberg giving the Palme to an American film – it would look like he didn’t even try – but if he does it will more likely be James Gray’s evocation of 1914 New York The Immigrant than the Coens. Sorrentino’s film exults in and condemns luxury with a brashness that doesn’t tend to win prizes, and I can’t see this jury wanting to hail a film that has as much sex in it as Blue has.

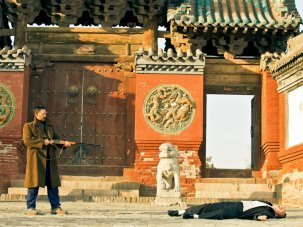

Does that mean, then, that Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin, his compendium of eruptions of violence from people marginalised by China’s hectic economic gold rush, now becomes favourite? As you can see, no one film feels right.

Manuscripts Don’t Burn

Intermission

The closer one got to the ends of both the Competition and Un Certain Regard programmes this year, the more one tripped over ever-more interesting films, so my first conclusion is that this has been one of the most consciously back-loaded Cannes of recent times. Even as I sat in Nice airport waiting for my plane I read glowing reports from those who’d seen the one major film I had to miss – Roman Polanski’s Venus in Fur.

My last day had included Manuscripts Don’t Burn, Mohammad Rasoulof’s chilling insightful portrait of dissident writers and the state-sponsored death squads who threaten them, Gray’s flawed but exquisitely made period drama The Immigrant and Jim Jarmusch’s drop-dead cool if patchy vampires-as-junkies comedy Only Lovers Left Alive. You don’t get many days more variously pleasurable than that.

Another thing I noticed is that we may have come to the end of the ‘slow cinema’ era. I saw only one film that matches that description, Lav Diaz’s magnificent, Dostoyevskian saga Norte, End of History, in which the actions of a philosophically minded law student activist prove tragic on the grand scale. Hard to know, though, if the reason for their absence is programmers becoming dissatisfied with that kind of cinema, filmmakers finding such films harder to finance or simple coincidence.

That absence may be one reason why the Un Certain Regard section has seemed much more exciting and revelatory than usual. Any of the films by Diaz, Rasoulof and Rithy Panh, or Hany Abu-assad’s magnificent political thriller Omar or could have been in Competition here, as indeed, according to other S&S writers, could Alan Guiraudie’s Stranger by the Lake.

Of course the Competition works in mysterious ways, is always political and there was even a sense that it was constructed to work for this particular jury, although having said that, it only contained three major disappointments: Arnaud des Pallières’ tedious Michael Kohlhass, Miike Takashi’s inept thriller Shield of Straw and, infamously, Nicolas Winding Refn’s Only God Forgives. The latter is a film so delicious to write about that I feel sure there will a torrent of critiques in its defence to match that of the Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw, who gave it a five-star review and suffered much abuse for it. I’m agin’ it myself, but you’ll have to wait for our next issue to see what I have to say about it.

-

Cannes Film Festival 2013 – all our coverage

See our previews, first-look reviews, festival roundups and awards reactions.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.