It’s unlikely that Károly Makk consciously established himself as the yang to Miklós Jancsó’s yin, but their careers had striking parallels. From the early 1950s to the early 2010s, each turned out dozens of films (many unknown outside their native Hungary) that typically revolved around a probing investigation into an aspect of the country’s complex political history. But where Jancsó was a flamboyant ringmaster, Makk favoured subtlety, introspection and a spare, unflowery style.

Born in Berettyóújfalu, eastern Hungary, on 22 December 1925, Makk worked up the film-industry hierarchy in the traditional way, starting as an assistant before graduating to screenwriter and director, making his debut in the latter capacity with Colony Underground (1951), co-directed with Mihály Szemes. He made his first international splash with his fourth feature (his second as sole helmer), the Cannes-competing comedy Liliomfi (1954), which was the first of ten collaborations with the actor Iván Darvas.

He maintained a regular output of roughly a film a year since then, but it was Love (1971) that secured him international attention again and which firmly established him as a modern master. Makk had spent half a decade trying to get it greenlit, only to be repeatedly stymied by its subject matter, the treatment of political dissidents during the Stalinist era and immediately thereafter. It was worth the wait, however, its incisive commentary on the lies people had to tell each other as a basic survival mechanism remaining one of the most potent portraits of life under totalitarianism ever filmed. Two great Hungarian actresses, Lili Darvas and Mari Törőcsik, play a mother and daughter-in law, the latter attempting to make the former’s last months easier by inventing an alternative, far more successful life in America for her political-prisoner husband (Iván Darvas, no relation).

Love (Szerelem, 1971)

Although he never matched the achievement of Love (a permanent fixture on Hungarian best-films lists), he nonetheless made other very impressive films. Cat’s Play (1973), in which women exchange letters that shed increasing light on their past lives played games with time and memory that recalled Resnais (or, more locally, Zoltán Huszárik’s then-recent 1972 masterpiece Szindbád), was Oscar-nominated.

A Very Moral Night (1977) was a comedy set in a brothel, whose employees concoct a subterfuge to hide the nature of their business from their lodger’s pure-natured mother after she pays them an unexpected visit.

Another Way (1982), a study of a doomed lesbian affair between two journalists, was a then extremely rare eastern European foray into gay subject matter (like Love, with a mid-1950s political backdrop), and in a remarkably non-judgemental way, perhaps because Makk seemed primarily interested in finding equivalence between political and sexual freedom. It caused sufficient controversy at home for Hungary’s then leader János Kádár to personally demand that it be withdrawn as the country’s Oscar candidate that year.

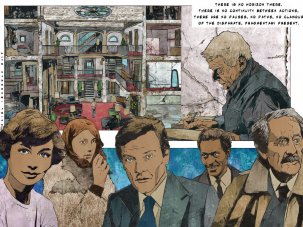

The Gambler (1997)

By then, Makk had amassed enough of an international reputation to start working abroad, in both West Germany (Deadly Game, 1982) and the US (Lily in Love, 1984; The Gambler, 1997). The latter, inspired not so much by Dostoevsky’s novel as its real-life inspiration (the novelist, played here by Michael Gambon, allegedly wrote it in less than a month to help pay off his own gambling debts), hit the headlines primarily for its casting of Luise Rainer in her first substantial big-screen role in many decades.

Back in Hungary, the late masterpiece A Long Weekend in Pest and Buda (2003) reunited him with Love’s stars Iván Darvas and Mari Törőcsik (with Eileen Atkins as Darvas’s English wife making up the third point of a love triangle) and showed that he’d lost none of his ability to sketch complex socio-political situations (once again, the 1950s cast a long shadow) with admirable deftness.

Sadly his final film, the political-corruption drama As You Are (2010), was not well received and has been little seen, but this was hardly going to dent Makk’s by now well-earned reputation as one of his country’s most distinguished postwar directors.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.