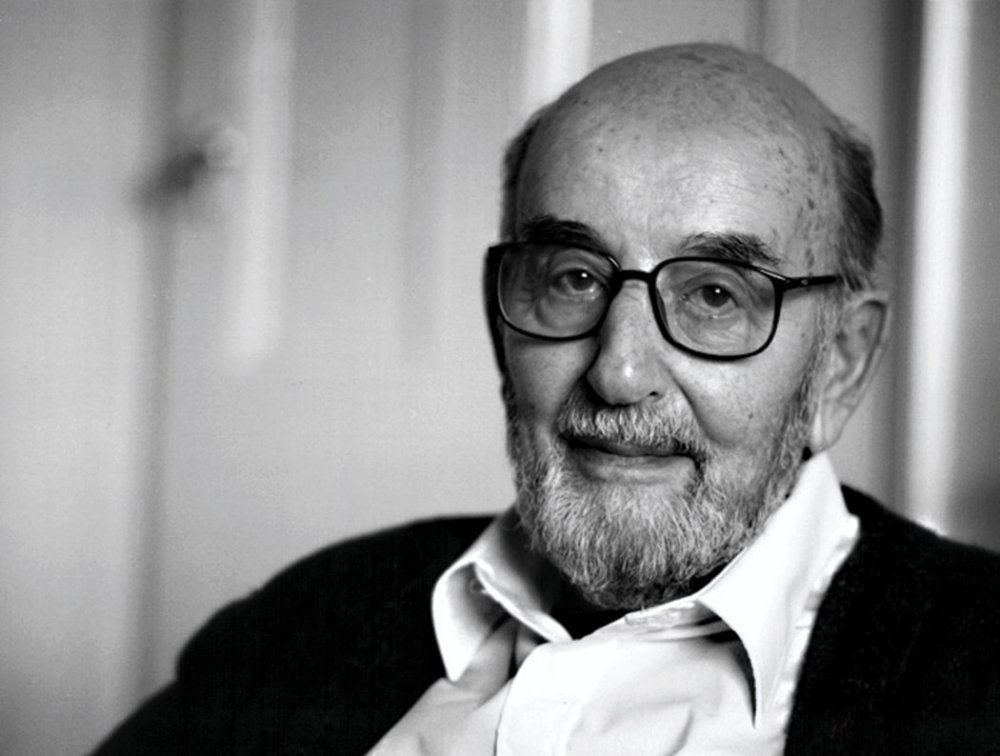

While simultaneously pursuing his photographic career, Suschitzky entered the movies while still in his twenties as a cameraman at Paul Rotha Productions – part of the Documentary Film Movement, whose civic commitment attracted him. In 1944 he was one of the Rotha employees, led by the charismatic Donald Alexander, who departed to form DATA (Documentary and Technicians Alliance), Britain’s first film cooperative. He was an active member for 12 years. Hoping to produce radical documentaries, DATA became best known for quintessential post-war consensus filmmaking: the National Coal Board’s cine-magazine Mining Review (which occasioned its makers’ exposure to, and deepening respect for, Britain’s coalfield communities).

Rotha’s fiction debut was also Suschitzky’s first feature: the unusual Irish tinker drama No Resting Place (1951). Jack Clayton’s The Bespoke Overcoat (1955) won an Oscar for Best Short, while Suschitzky’s first foray into TV came via episodes of a Charlie Chan series. Through the next decade, he alternated quirky features, ads and a steady stream of nonfiction shorts (an increasing number of them in glossy colour, directed by such established but underrated documentarists as Sarah Erulkar, Peter de Normanville and Paul Dickson). He also worked with rising talent: for Hugh Hudson, for instance, he shot several corporate films and many commercials. From the late 1960s, Suschitzky was increasingly in demand as a feature DP, though he never abandoned his nonfiction origins, still photographing industrial training films as late as the 1980s.

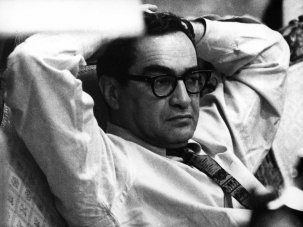

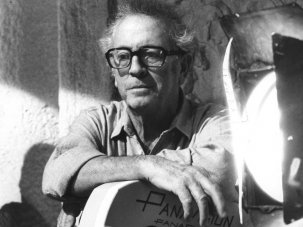

Suschitzky has been retired since 1987. This lifelong filmgoer remains a dedicated one, regularly spotted at screenings. Usually with partner Heather Anthony, sometimes solo, he comes by bus, takes the stairs, and often ends his evening with some red wine. “Art can be produced with any medium,” he insists, “but only in the hands of an artist. Unfortunately there are not many of those about. I certainly don’t claim to be an artist. I am content if I am considered a craftsman.”

Man with a movie camera: 19 of Wolfgang Suschitsky’s finest moments

Children of the City

Budge Cooper, 1944

This Paul Rotha production is a stark study of Dundee poverty. More social-democratic films would follow in Suschitzky’s DATA years, including the trio below.

Cotton Come Back

Donald Alexander, 1946

► Watch Cotton Come Back on BFI Player

Education of the Deaf

Jack Ellitt, 1946

Fair Rent

Mary Beales, 1947

► Watch Fair Rent on BFI Player

The Bridge

J.D. Chambers, 1946

Two-man unit Chambers and Suschitzky shot this fascinating record of reconstruction in post-war Yugoslavia, in tough conditions.

Mining Review

various directors, 1948-56

► Watch Mining Review 4th Year No. 12 on BFI Player

► Watch Mining Review 6th Year No. 5 on BFI Player

Suschitzky’s contributions to the early years of the world’s longest-running industrial newsreel exemplified its strengths: unassuming, economical artistry, technical exactitude and a generous, unforced optimism that’s bittersweet in retrospect.

The Bespoke Overcoat

Jack Clayton, 1955

Adapted from Gogol, this award-winning short bridged Suschitzky’s documentary and feature careers, revealing a latent mastery of interior cinematography laced with ghostly expressionism.

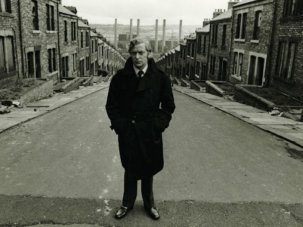

The Small World of Sammy Lee

Ken Hughes, 1962

An excellent, energetic British genre pic, dripping with authentic Soho atmosphere, thanks not least to incredibly mobile off-the-cuff, on-the-streets camerawork.

Lunch Hour

James Hill, 1962

By contrast with The Small World of Sammy Lee, this flawed, fascinating curiosity, from a John Mortimer script, is improved no end by the way the photography accentuates its intense claustrophobia.

Stone into Steel

Paul Dickson, 1960

Industrial documentary at its most majestic. Elemental yet futuristic, this is silent cinema for the 1960s, in Eastmancolor.

Snow

Geoffrey Jones, 1963

A great short is a thing of joy forever. Several weeks’ heavy-weather shooting yields nine minutes of gleaming camerawork, rhythmically cut to evoke – everlastingly – a notoriously bad winter.

The River Must Live

Alan Pendry, 1966

This Shell short launched the strange cycle of contemplative environmentalist films sponsored by oil companies. Suschitzky’s evocations of nature, spoilt and unspoilt, were crucial to its impact.

The Tortoise and the Hare

Hugh Hudson, 1966

Corporate film with a difference. This novelty hit from the future director of Chariots of Fire is a thoroughly enjoyable, pleasingly dated modern fable, sponsored by Pirelli tyres and set on Italy’s roads.

Ulysses

Joseph Strick, 1967

Joyce’s proverbially ‘unfilmable’ book prompts an inevitably imperfect film – but an underrated, creditable, rewarding one. The first-rate photography reflects Suschitzky’s absorption in a novel he reread many times.

Cast Us Not Out

Richard Bigham, 1969

Among many moving NGO films, this conscience-pricking documentary (directed, by the future Viscount Mersey, for the Jewish Welfare Board) stands out for its candour, clarity and caring attention to careworn faces.

Entertaining Mr Sloane

Douglas Hickox, 1970

This fine Orton adaptation was one of Suschitzky’s frequent collaborations with the flamboyant Hickox, remembered by the DP as a man without “a subtle bone in his body”. See also Theatre of Blood (1973), starring Vincent Price.

Worzel Gummidge

James Hill, 1980-81

The subtle camera mood changes are quintessential Suschitzky, crucial to the atmosphere – bucolic, autumnal, a little sinister – of this children’s TV series, which lingers in the memories of many of today’s middle-aged.

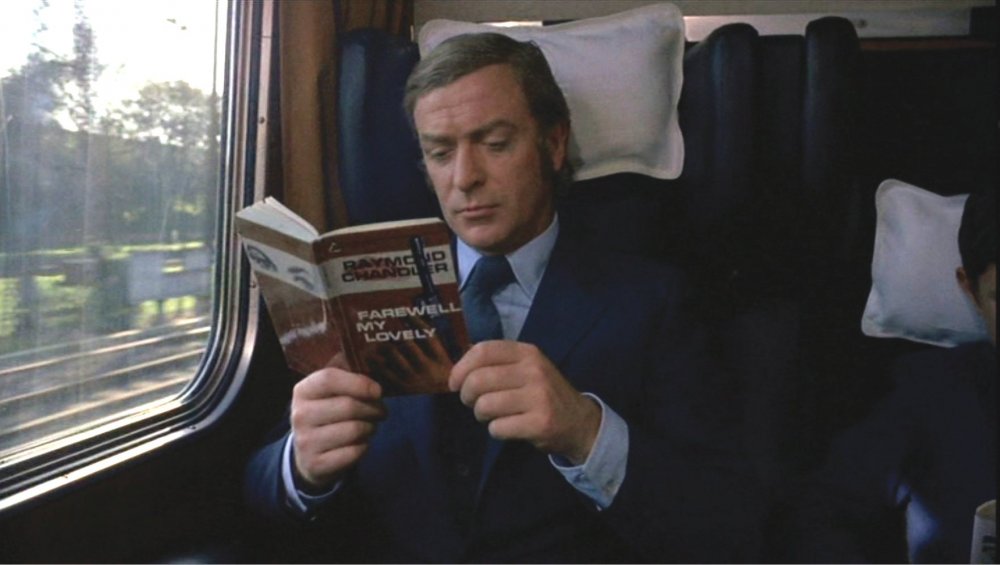

Staying On

Silvio Narizzano, 1980

This TV adaptation of Paul Scott’s novel reunites Brief Encounter’s Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard as a British couple remaining in India after the end of the Raj. Suschitzky remembers being reduced to tears by Johnson’s performance.

The Chain

Jack Gold, 1984

Ensemble comedy as social commentary, Suschitzky’s last major feature is – in photographic terms – as deft a mix of locations, moods and modes as his career high Get Carter.

-

Sight & Sound: the August 2012 issue

The genius of Alfred Hitchcock: Guillermo del Toro on the Master of Suspense; plus Christopher Nolan, Patricio Guzmán, Bruce Lacey, Boris Barnet,...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.