Web exclusive

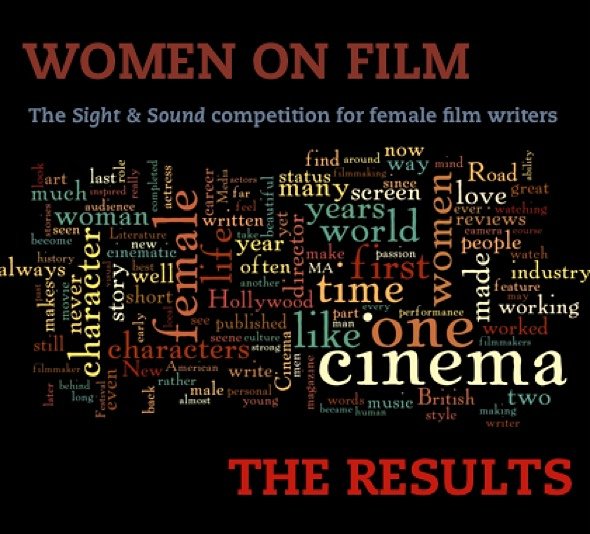

We’re delighted finally to announce the results of our Women on Film competition.

To recap, concerned about the deficit of female voices in the world of film criticism (including in our own pages), we elected to hold a competition to encourage more women to offer up their views. Has the entire art (and industry) of cinema become too male-oriented and off-putting to women? We decided to invite women to essay what – or indeed, who – they found inspiring in the world of film. In other words, we wanted to read about what would motivate you to write film criticism or commentary, as well as to see the evidence that you can do it.

Writing about the things you admire – at once conveying your enthusiasm and explicating it – is one of the more uphill challenges of the reviewer’s art. As we wrote: “We’re interested in your heroes, models and muses, but also in your critical acumen: your writing should be passionate and imaginative but also insightful and analytical.” Our three judges – our editor Nick James, critic Catherine Wheatley and the BFI’s Creative Director Heather Stewart – went in search of that golden mean of well-phrased evaluation.

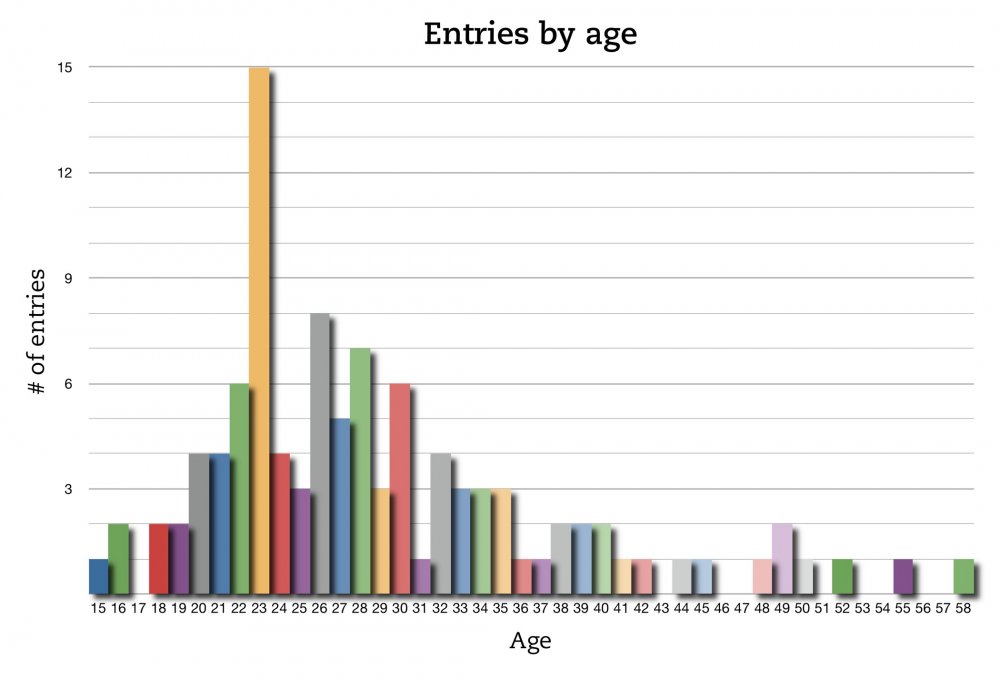

We received 106 entries from around the world, on a range of fascinating subjects spanning actors, directors (and more directors), sundry other film workers, fictional characters, and indeed films, notwithstanding the competition rubric’s emphasis on writing about people. Unsurprisingly – but enjoyably – the submissions ran the gamut, from familiar to esoteric subjects, in more or less concentrated language.

It’s taken us a while to process all the results – we’ve tried to give the entries we’ve published online the same rigorous editing we provide a professional writer, while preserving their unique and often idiosyncratic flavours. Thanks to everyone who took part, and has waited for the results. And congratulations to the following four writers…

The winner

Thirza Wakefield

Nottingham, UK

Of actresses neglected in the age of digital video, there are none so inspirational as Margaret Sullavan (1909-1960). If lucky, most of us make her acquaintance – as the conceited shop-assistant, Klara Novak – in Ernst Lubitsch’s The Shop Around the Corner (1940), a film which showcases her tremendous gift for comedy but is by no means her best.

Sullavan made her first screen appearance just a decade after the popularisation of talking pictures – and how it shows. Seldom have actresses been granted so much screen time unscripted, but Sullavan warranted it: flat-featured, like a Pierrot under wet white makeup, with eyebrows now blown, now collapsible as parachutes – not the painted arabesques of her contemporaries.

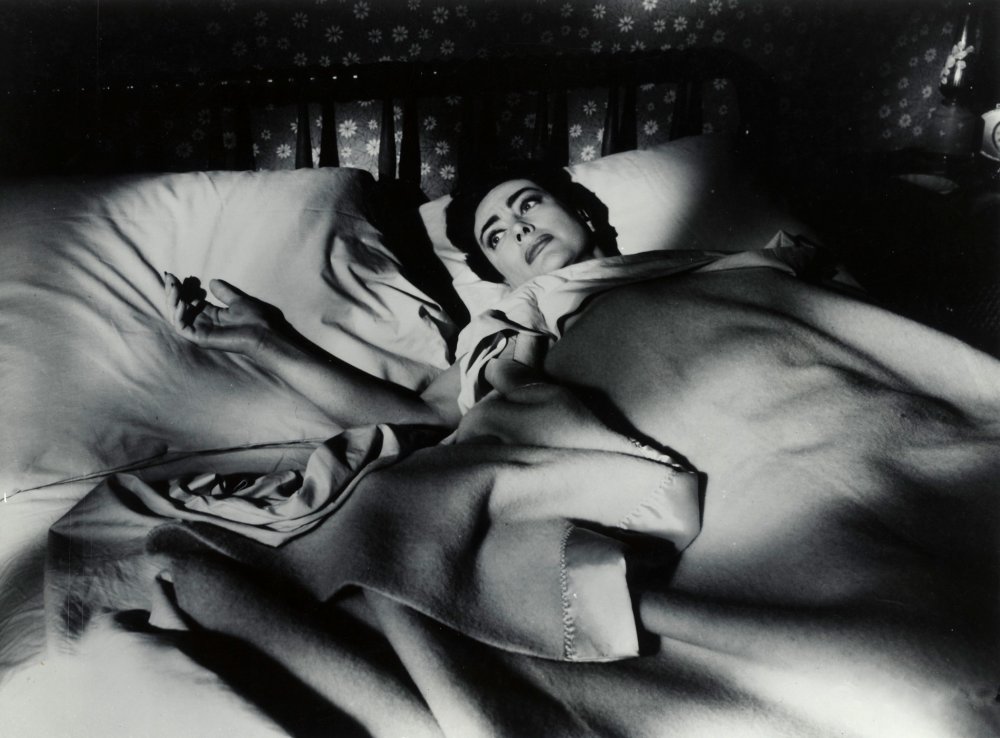

Margaret Sullavan in Next Time We Love (1936)

As a brittle Broadway actress in The Shopworn Angel (1938), she cuts James Stewart’s Texan soldier to paper ribbons; and as the naive, newly-wed Lammchen (Little Man, What Now?, 1934) she makes hilarity out of piteousness when, side-saddle on a carousel pony and aloft of her husband, she confesses to having eaten his share of their dinner. (Only Sullavan, with her silent-era expressiveness, could justify a full five revolutions of the carousel.)

Sullavan made only 17 films – an uncommonly small estate for a leading, contracted actress in this era of Hollywood filmmaking. Taking exceptional interest in the quality and production of her work, she acquired a reputation for ‘strange behaviour’. It is apparent now that this notoriety – her so-called strangeness – had little to do with her appearing on the cover of Life in silk pyjamas and more to do with her female determination in a male-dominated industry.

It is significant – perhaps a genuine peculiarity – that Sullavan’s interventions were never intended for her own advancement. Her perseverance in the matter of hiring Dorothy Parker to rewrite the dialogue for The Moon is Our Home (1936), and in the casting of James Stewart in his first substantial role, seems to me expressive of an investment in the talents of others, a collaborative generosity, and as such is something to be commended. No, Sullavan mustn’t be forgotten, but remembered for what she most certainly was: one of the greatest and ungovernable talents of twentieth-century cinema.

- Thirza wins a year-long mentoring programme with our critic Catherine Wheatley, plus a commission to write a longer feature for this website.

The runners-up

1. Emily Ryan

Irvine, California, USA

One of my film inspirations is Robert Aldrich’s Autumn Leaves (1956, above). It brought to life one of my favourite characters, the hopeless and middle-aged Millicent Wetherby, who carries a monogrammed handbag and dreams of chicken salad at a deserted diner. This bizarre woman, played by a 51-year-old Joan Crawford, is a fantastic creation. At the beginning of the film, we understand that she has been enduring a solitary business and social career: she’s a typist who trades in a pair of symphony tickets at the box office for a pricier seat for one.

Autumn Leaves (1956)

Life begins when she reluctantly agrees to share her booth with Cliff Robertson’s Burt Hansen. Aldrich sets her up the most tarnishing sort of defeat at the hands of this younger manipulator. Crawford’s portrayal of the naïve Millicent is expert and intriguing, her legendary silhouette somehow wrenched into plainness. She offers an arsenal of self-conscious traits, which includes a girlish, manic pronunciation of “Okay!” as Burt loutishly suggests they go Dutch. We soon stop seeing Joan and start recognising Millicent, a mature woman who makes missteps in the search for love.

Aldrich has been described as having a penchant toward the psychotic and physically unkempt, but his decision to pair well-known actresses with peculiar or fringe material has yielded legendary performances. In Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964) and The Killing of Sister George (1968) he presents grotesque scenes of jealousy, aging and desire. Setting aside his well-known high camp, epic action and comedy hits, Aldrich’s story of solitude is still my favourite theme. In the face of these gruesome Technicolor heroines in their overly powdered skin and papier-mache eyelashes, we have the monochrome Millicent, emerging from the cabana: all neck and legs, stripped of her protective shadow.

Here, Aldrich captures the erstwhile Queen of Hollywood in a skilled portrait of anonymity.

- Emily wins an annual subscription to Sight & Sound.

2. Anna Valdez Hanks

London, UK

When judged on audaciousness and distinctiveness, Belgian director Chantal Akerman has few peers. Through her singularly austere direction, Akerman’s early films, such as Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) and Les Rendezvous d’Anna (1978), created a reflexive cinema that was startlingly original in form.

Frequently moving between narrative and non-narrative forms, many of her films contain elements of both. Her documentary D’Est (From the East, 1993) can be seen as a pinnacle of her singular vision. Made in 1993, it is a series of shots filmed in the demised Soviet bloc, from East Germany through to Russia. The camera tracks slowly past tenements and unending rows of people waiting – merely waiting – perhaps to cross the road, or for buses. The faces are deadened, as though literally stultified by blows from the hammer and sickle. They seem like tableaux vivants, or actors waiting to hear action. Closer to music than to conventional cinema, D’Est is an intoxicating evocation.

Chantal Akerman in Saute ma ville (1968)

Akerman’s 40 or so films vary enormously in their artistic integrity. Her later output is a disturbingly poor mix of genre pastiche films that contain no sign of her earlier vigour. Nevertheless, Akerman has done what few directors can claim: to realise new possibilities in cinema.

I see Akerman’s cinema as part of the brutalist movement of the 60s and 70s. Brutalism in architecture is epitomised by unrelenting concrete buildings: an extreme type of modernism. For its admirers, the purity of brutalist form is a kind of poetry.

The quality of Akerman’s early films mirrors this architecture. Ironically the pleasures of brutalism lie in its exaltation of what is usually seen as modernity’s base by-products. Akerman focuses on modern human miseries: domestic drudgery, isolation, and emotional deprivation. She contains these concepts, re-ordering them in her unique cinema. It is the sheer force of Akerman’s pure creative vision that commands us to attend to her art.

- Anna wins an annual subscription to Sight & Sound.

Also commended

Julia Bell

London, UK

As with most of my film heroes, I discovered Lynne Ramsay just as I was starting to find out what cinema could be. I’d seen and loved much stranger and bolder films before, but her debut feature Ratcatcher (1999) pulled me close and spoke to me directly. Like the Glaswegian dialect in the film, it was a familiar but foreign language. A change of tone and pace.

She was not afraid to linger in silence if the scene required it, yet the storytelling was economical, even elliptical, with no excess flab. I leaned in closer to take in her photographer’s focus on small gestures and textures: children’s bored fascination with tracing patterns in mounds of table salt; the reeds and grit clinging to the face of a drowned boy. She showed me how a scene could be startling in its stillness or even its silence.

While her voice was markedly different, it was not a recognisably feminine one, but all the more appealing for its ambiguity. She portrayed childhood as brutal, sexualised and laden with guilt and unease, yet simultaneously foregrounded moments of tenderness or silly sweet imagination: a boy adjusting a holey stocking over his sleeping mother’s toe; a mouse, tethered to a balloon, sailing through space to land on a cheese-decked moon.

Hearing her speak on stage a few years later, I was struck by her conflicting confidence and vulnerability. “I resent that!” she rebuked her interviewer, for suggesting that “not a lot happened” in her second feature Morvern Callar (2002), a story about a young woman who butchers and buries her boyfriend’s body before passing off his unpublished novel as her own and taking an extended trip to Spain. Thus it was surprising to learn that Ramsay would not have been on stage at all that night had she not been granted special permission to smoke throughout, to calm her crippling nerves.

Criminally underemployed since Morvern Callar, Ramsay has at last completed her third feature [We Need to Talk About Kevin]. I can only hope that this will mark a welcome change of pace for her too.

Entry breakdowns

View Women on Film entries by location in a full screen map

-

Women on Film – all our coverage

A window on our ongoing coverage of women’s cinema, from movies by or about women to reports and comment on the underrepresentation of women...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.