Web exclusive

Inland (2001)

If the words ‘Swiss’ and ‘musical’ make you think of Alpine meadows and hills alive with the sound of music, think again. Made between 1989 and 2012, the 14 films in this year’s Musical Documentaries from Switzerland strand at Wroclaw’s New Horizons film festival – which has made films about music and contemporary art its signature since it was established in 2001 – attempted to steer clear of stereotypes by showing the different guises of what’s evidently a flourishing documentary genre in Switzerland, judging by the sheer volume as well as the quality of the films.

|

13th New Horizons International Film Festival English-subtitled DVDs of Heimatklänge, Inland and Magic Radio, and DVDs and Blu-rays of Fritz Hauser, Klangwerker, are available from artfilm.ch. Peter Liechti sells DVDs of his films at peterliechti.ch. The 2013 edition of Bristol’s Encounters Festival of short film and animation, running 17-22 September, will feature a Swiss theme, including special retrospectives, sidebars on Yves Netzhammer and Marie-Elsa Sgualdo, and a live soundtrack to a montage of Dadaist classics performed by Franz Treichler of The Young Gods. |

True, native sounds like yodelling and peculiar traditional instruments like the alphorn or the diminutive Jew’s harp do feature in Iwan Schumacher’s 1999 Trümpi – Anton Bruhin – Der Maultrommler (Anton Bruhin – the Jew’s Harp Player), in Pierre-Yves Bourgeaud’s Inland (2001), about the experimental duo Stimmhorn, and in Stefan Schwietert’s 2007 Heimatklänge (Echoes of Home), in which Stimmhorn’s Christian Zehdner also appears. When asked in the latter, “What’s the sound of Switzerland?”, Zehdner responds that to him it’s the sound of trains, cow bells and milking machines; the day he heard one of the latter, he realised it had a groove.

So far, so clichéd. But genre specialists like Bourgeaud and Schwietert, who each have ten or so music documentaries to their name, tackle the clichés head on. In Heimatklänge, Zehdner acknowledges that yodelling – a voice modulation technique devised by herders to carry their calls far across valleys – initially put him off because of its associations with men wearing Appenzell costumes or Tyrolese hats.

In that vein, Anka Schmid’s Yello (2005), a colourful hour-long documentary about the wacky Swiss electro pop band which weaves original Yello video clips into its fabric, shows grinning band members Boris Blank and Dieter Meier (who attended the festival) riding funicular railways against a backdrop of Swiss chalets and snow-covered slopes.

Yello (2005)

Whether classical, jazz, folk, experimental or free improvised, music in these documentaries is strongly connected to place. But that place needn’t be Switzerland. The 14 selected films are Swiss musical documentaries to the extent that they’ve been made by Swiss filmmakers.

A Swiss-French production, jointly directed by Luc Peter and Stéphanie Barbey, Magic Radio (2007) well conveys the vital role radio still plays in Nigerian society as an educational, recreational and political tool.

Liquid Land (2012)

Liquid Land (2012), Michelle Ettlin’s directorial debut, focuses on New Orleans’ free-improvised music scene, much less well known than the city’s jazz, blues and heavy metal. In a series of compelling interviews, Ettlin elicits intimate revelations from local improvisers about what it is that makes them stay in the city against all (climactic) odds, and takes the pulse of the place five years after Hurricane Katrina. The impulse behind the film came from a Swiss and a Dutch experimental musician who travelled to New Orleans to meet fellow improvisers working there.

Like Liquid Land, a number of these films take encounters between musicians as their starting point. Erich Busslinger’s 2011 Fritz Hauser – Klangwerker (Fritz Hauser – Sound Explorer) stages a meeting between the eponymous avant-garde percussionist and composer and the improviser Fred Frith.

Balkan Melodie (2012)

Schwietert’s Balkan Melodie (Balkan Melody, 2012) meanwhile charts ethnomusicologist and producer Marcel Cellier and his wife Catherine’s life-long passion for folk music from the Balkan region where they travelled when it was still off-bounds for Western visitors. Cellier is credited with discovering such talents as Romanian flute virtuoso Gheorghe Zamfir and the Bulgarian female choir behind the bestselling Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares albums. The film raises such thorny issues as author’s rights in folk music, since Zamfir accused Cellier of exploiting his music to commercial ends and eventually broke off all relations with the Swiss couple.

Family ties of a more or less conventional kind were another recurrent theme. In Family Music (2004), the second of his films shown as part of the programme, Borgeaud combines interviews with Austrian jazz musicians Christian and Wolfgang Muthspiel, footage from their concerts and homemade videos shot in super 8 by their father, who instilled family values in his sons, to show how the connection between the two brothers plays out in their music.

Equally composite but far less earnest, Stéphanie Argerich’s Bloody Daughter (2012), a filmic portrait of the temperamental Argentinian concert pianist Martha Argerich by the youngest of her three daughters (each from a different father), depicts the foibles and the vulnerable side of her ageing mother, as well as her own attempts at asserting her creative independence.

Les Reines Prochaines (2012)

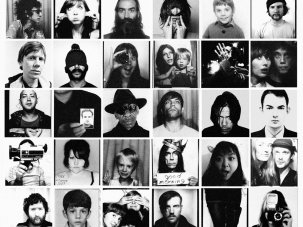

What ageing means to a female performer is also touched on in Claudia Wilke’s Les Reines Prochaines (2012), a comical group-portrait of the Dada-inspired feminist Swiss girl band of the same name.

For all the broad range of trends and genres covered in this festival strand (curated by Jan Topolski, editor of the Polish music magazine Glissando, which last year ran a special issue on Swiss music), the music in these films tends to be of the experimental variety. Yet the way of filming this kind of music seldom breaks new ground.

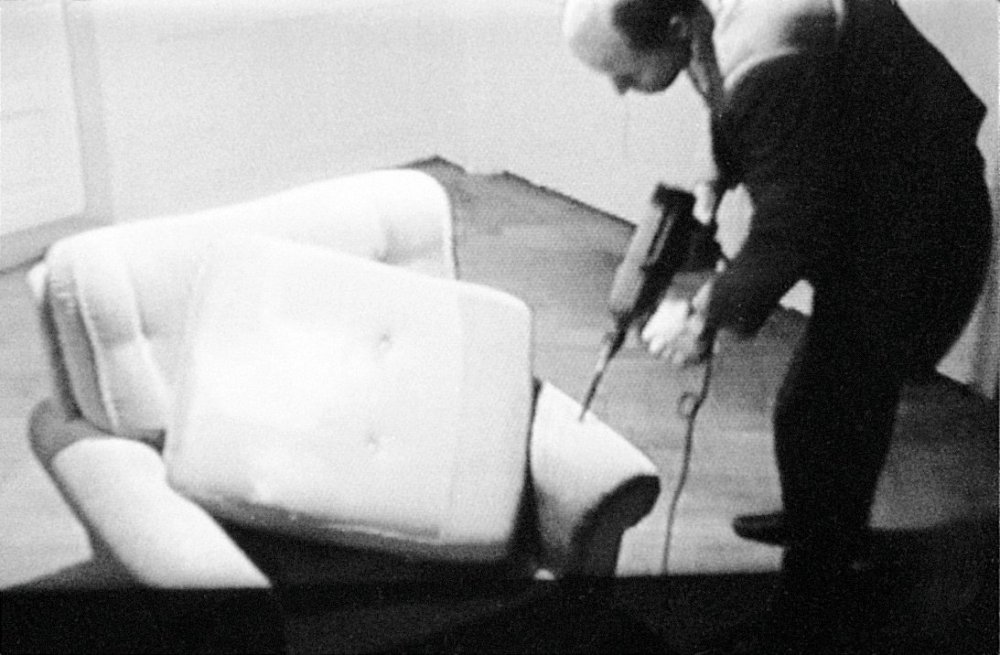

Kick that Habit (1989)

As a result, the rare films that shun a traditional interview-based, narrative-led approach to documentary filmmaking stand out. In both Inland and Peter Liechti’s Kick that Habit (1989), an early collage portrait of electroacoustic pioneers Voice Crack by the director of the acclaimed 2009 documentary The Sound of Insects – Record of a Mummy, dialogue is done away with altogether, which may be why the viewer’s attention is firmly focused on sound and its visual source. In these films, vision and hearing appear to be on an even footing; if anything, sight follows sound for a change.