from our December 2014 issue

Citizenfour (2014)

One of Sight & Sound’s best films of 2014.

For those who do not recognise Edward Snowden’s revelations of enhanced domestic spying capabilities as intrinsically terrifying, the assurance largely goes that if you’ve nothing to hide then you’ve nothing to fear from machines built to record all possible data about you. Snowden also has his critics who argue that his flight from both line-managers and prosecutors undermines his moral case and forfeits what President Obama, excerpted here, po-facedly dreams could have been an “orderly… thoughtful, fact-based debate” that would have “led us to a better place”.

USA/South Africa/United Kingdom/Germany 2014

Certificate 15 113m approx

Director Laura Poitras

In Colour

[1.78:1]

Distributor Artificial Eye Film Company

UK release date 31 October 2014

citizenfourfilm.com

► Trailer

Convicted WikiLeaker Chelsea Manning is not mentioned, but these notions are otherwise countered in Laura Poitras’s film by the experiences of NSA veteran-turned-dissident William Binney (the subject of her previous short The Program), never questioned by Congress but escorted from his shower one morning by government agents at gunpoint, and by AT&T customers’ class-action suit against warrantless governmental wiretapping, stalled in court for a decade.

Snowden and others verbalise many of the actual and hypothetical arguments for privacy – the chilling, self-policing effects of “the expectation that we’re being watched” on online intellectual exploration; the improbability of “meaningfully opposing” changes to surveillance policy once the systems have been built. Brits recently regaled with revelations of undercover officers spying on murder victims’ families and infiltrating the beds of environmental campaigners may also be inspired to imagine the worst.

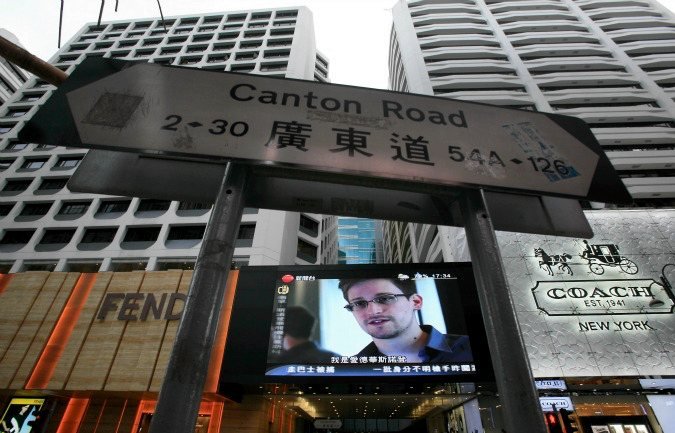

But far from just trading in conjecture and abstraction, Citizenfour self-reflexively dramatises the dangers that Snowden wants to warn us about. Built around the eight days in June 2013 he spent with the filmmaker and Guardian journalist Glenn Greenwald in a Hong Kong hotel room divulging his secrets, the film plays like a reality cat-and-mouse spy thriller, with the trio out to expose the dragnet before it catches them. Electrifyingly, the film shows us history in the making. Has such a political actor ever before gone direct to a filmmaker in the heat of the action?

Citizenfour (2014)

To be sure, there are questions of nuance and balance you’ll not find in this film, with its self-selecting cast of liberty advocates. Poitras had already wised up about US government watchlists the hard way, after 40-plus airport interrogations in the years following her work filming Iraq’s 2005 elections and their boycott in My Country, My Country. She was already exploring a film about US surveillance (to complete a trilogy about American policy after 9/11, following 2010’s The Oath, about Yemeni ex-jihadis and Guantanamo Bay), and came to Snowden’s attention through her film about Binney. Her journalistic ally Greenwald had written about her travails before Snowden recommended that she bring him with her to their Hong Kong rendezvous, and he constitutes one of the most strident, and eloquent, voices in the film; he leaps on the information trove and immediately, brilliantly, sets to battle.

This Hong Kong hotel chamber drama is, unsurprisingly, the heart of the film. Poitras tops and tails with other voices (Binney and hacker Jacob Appelbaum, as well as security chiefs James R. Clapper and Keith Alexander) and locations, from the supersize data centre the NSA is building at Bluffdale, Utah, to the Guardian’s basement and the parliaments of Brazil and Germany. But Snowden, in sundry monochrome T-shirts and later a hotel robe, is the earnest, fresh-faced, unlikely calm at the centre of his storm.

Unlike in Poitras’s earlier studies of decision-making in the moment, Snowden has already set out his stall: we watch him watch the consequences. He’s remarkably lucid setting forth his motivations and defending his methods: he’s entrusting professional journalists to decide what’s in the public interest and wants to “remove his bias from the equation”; you could torture him and he wouldn’t be able to divulge encrypted passwords; if he were doing this for profit there’d be far easier ways; he doesn’t want to become the story but “anything to get this out”; and he wants the target painted “directly to my back” to take the heat off his family. He must have endlessly rehearsed all this to himself.

Citizenfour (2014)

A wry paranoia often prevails – in Snowden’s attempts to teach Greenwald basic computer-security sense; in the cloak, termed by Greenwald his “mantle of power”, under which Snowden hides to input computer passwords; and in the black-comical barrage of phone calls and fire alarms that later interrupt their discussions. Snowden is at his most shaken after an update from his forsaken girlfriend, and perhaps when the prospect of an escape route finally presents itself. But the basic optimism of his actions is reflected in one characteristic exchange, when he responds to Greenwald’s rallying cry about not being bullied into silence by expressing hope that the “internet principle of the Hydra” will apply, and that “seven more will step up when I’m gone.”

As it happens, Poitras is able to end on something of that note, finding Snowden now in his Russian sanctum, rejoined by his girlfriend. The news from Greenwald is that a more senior whistleblower has emerged from another part of the US government.

Details are scanty, partly because this brings the film into the present moment, and partly because Greenwald and Snowden communicate here in handwritten notes which they then shred, though the information in question seems to relate to recent revelations about the government’s terrorism watchlist and a direct command line to the US president. Just as Alex Gibney’s We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks (2013) cautioned against blind faith in leaders, so Citizenfour is shadowed by an erstwhile reformer who rode social and digital optimism to the White House. Poitras ends on a shot of the shreds of paper. The revolution will not be emailed, or recorded, or spoken. But it could still make thrilling cinema.

In the September 2014 documentary special issue of Sight & Sound

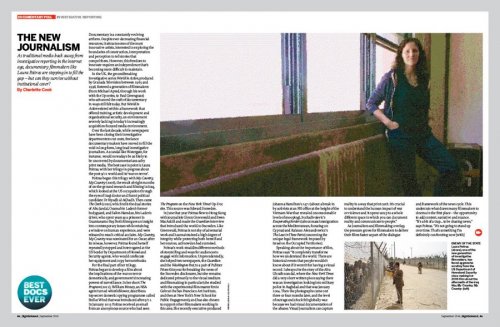

The new journalism

As traditional media back away from investigative reporting in the internet age, documentary filmmakers like Laura Poitras are stepping in to fill the gap – but can they survive without institutional cover? By Charlotte Cook.

-

Sight & Sound: the December 2014 issue

The making of 2001: A Space Odyssey, plus David Thomson on westerns, the rise of Christianity movies, Winter Sleep, Leviathan, Life Itself and much...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.