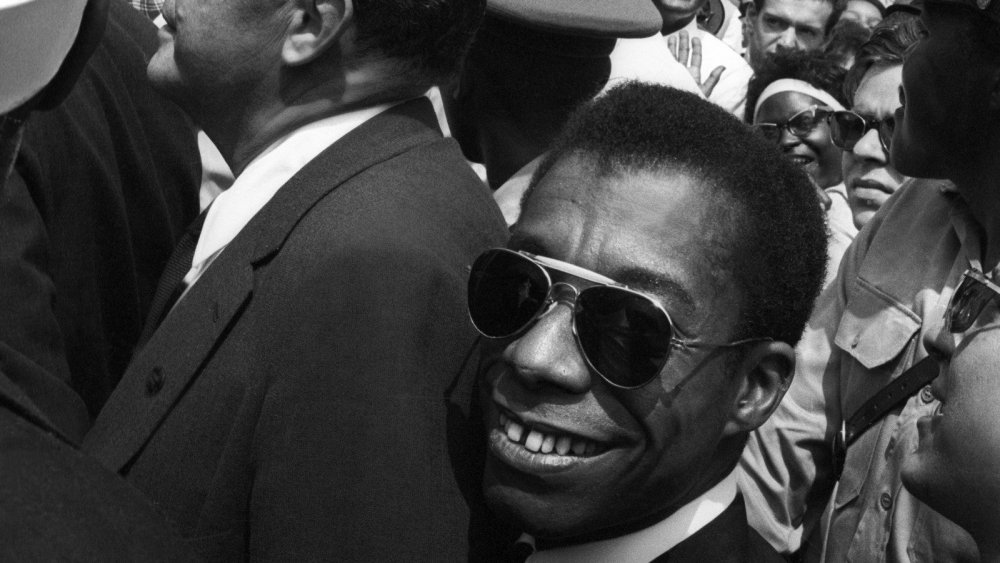

As part of a 1961 radio panel that included fellow black literary luminaries Lorraine Hansberry and Langston Hughes, James Baldwin remarked: “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time. So that the first problem is how to control that rage so that it won’t destroy you.”

Switzerland / France / Belgium / USA 2016

Certificate 12A 93 mins

Director Raoul Peck

Colour and black & white

[1.78 : 1]

UK release date 7 April 2017

Distributor Altitude

movies.powster.com/i-am-not-your-negro

► Trailer

The agonising succinctness of this statement – so tight and perceptive, extemporaneous and journalistic – makes its truth sting that much more. It’s no doubt because of that furious, acidic crispness of his words that it’s Baldwin, not Hansberry, Hughes, Ralph Ellison or any other highly influential African-American writer of the 20th century, who has enjoyed a resurgence in the era of limited characters and outrage. (Baldwin secured his spot as a mid-century public intellectual through his media appearances, in part prepared by his years as a preacher in Harlem.) As Raoul Peck repeatedly demonstrates in I Am Not Your Negro, this anger is timeless, unwavering and (do I really need to say it?) completely justified; it is inseparable from the American experience.

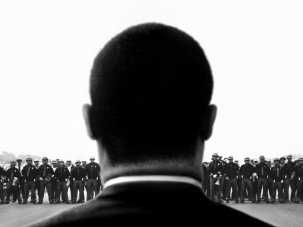

Peck’s documentary begins with Baldwin’s unfinished book Remember This House, which intended to grapple with the lives and deaths of three civil rights leaders (Martin Luther King Jr, Malcolm X and Medgar Evers) who were also his friends. Baldwin’s words are brought to life by the raspy, hushed voiceover of Samuel L. Jackson, who gives his best performance in more than a decade. With access to the author’s entire archive, Peck uses photographs and television clips of Baldwin with these three figures to ‘illustrate’ their relationships, but also uses pictures of the men in similar but separate places to create the illusion that they were together at times they weren’t. It may seem like a small, typical doc trick, but the rhythms established through Alexandra Strauss’s editing stitch these images together in a way that makes them coherent and lively, filling in the gaps in historical records: although the men weren’t always photographed together, they were very often together.

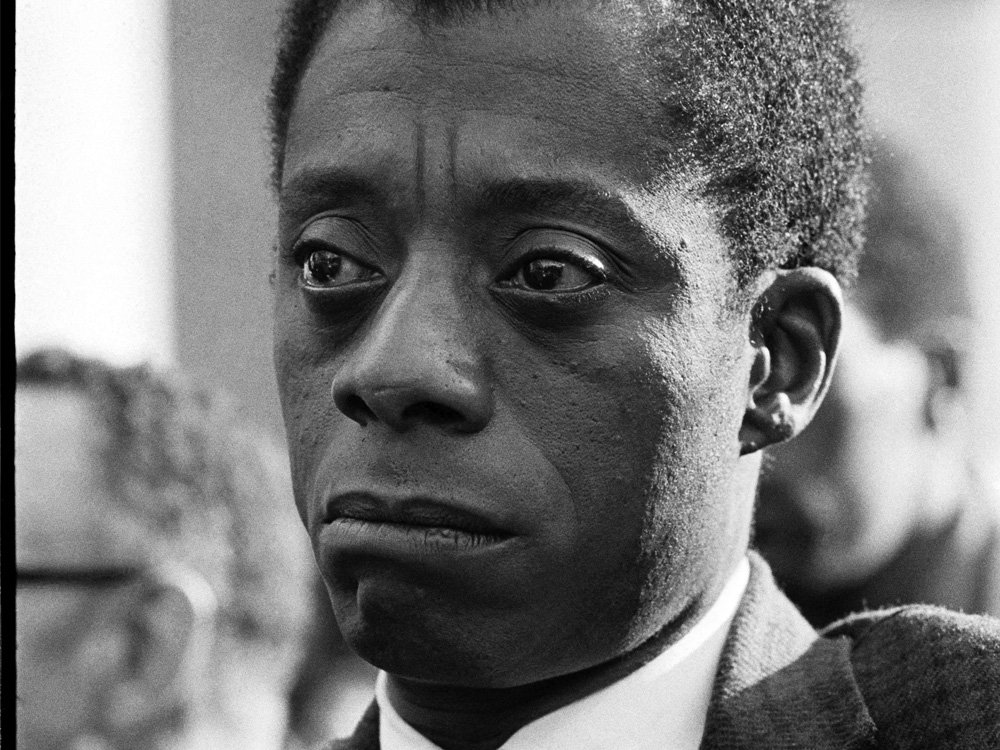

I Am Not Your Negro (2016)

Credit: Getty Images

After outlining the concept of the book and exploring the climate of the era (including a news clip of a pro-segregation woman claiming that God will forgive murder but not miscegenation), Peck begins using passages and ideas from The Devil Finds Work, Baldwin’s 1976 book about cinema. Because of the cohesiveness of Baldwin’s words and approach, this switch isn’t so jarring: his inability to find a man akin to his father at the dream factory, save for a blubbering prisoner who just looks like him, is crucial in the understanding of race in America. This disconnect between what Americans are told the country stands for (a place where everyone is free, a land of opportunity and scenic beauty) and what it actually is for millions (a place where the police, whose salaries are paid with all citizens’ taxes, are disproportionately more likely to kill you if you’re black) eventually becomes the main argument of Peck’s documentary.

Through montage and Baldwin’s words, the film deconstructs images of white heroism (such as John Wayne), racial forgiveness (such as Sidney Poitier falling off the train with Tony Curtis in 1958’s The Defiant Ones) and the function of the N-word itself (as Baldwin says on The Dick Cavett Show in 1968, “If you think I’m a nigger, it means you need it…”). A particularly jarring instance is the pairing of a blasé industrial film titled The Land We Love (1966) with footage of the Watts riots in 1965, and seeing, in addition to the absence of black faces in the former, how the American Dream is a wonderful dream but is also used as a nightstick to beat those who have been systemically prevented from enjoying it. (See also: the ‘pull up your pants’/All Lives Matter crowd.) Lovely images can hurt just as much as ugly ones.

I Am Not Your Negro (2016)

More than simply weaving together Baldwin’s thoughts in an incisive, poetic way, what makes Peck’s film truly remarkable is how it repeatedly connects the writer’s thoughts not just to the present but to all of American history and its visual culture. The pandemonium of white bodies at a picnic in a Technicolor musical turns into the pandemonium of black bodies being subjected to police brutality; early photographs of black men and women, likely counting among W.E.B. Du Bois’s ‘talented tenth’, transition to filmed portraits of African Americans in the present day confronting the gaze of the camera; we see plantation stereotypes and blackface evolve from burnt cork to coded, subservient subjects in advertising. This stream-of-consciousness approach to history is always critical and never forced: as Baldwin describes the idea that crime is only perpetrated by “a handful of aberrants”, vintage footage of a group of black teenage boys being led to a maximum-security prison is juxtaposed with the harrowing images of (white) mass shooters and a clip from Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003). Without putting too fine a point on it, Peck shows how these uniquely American myths can swing both ways.

Despite covering all this ground, Peck rather oddly avoids a crucial aspect of Baldwin: his sexuality. Save for an excerpt from his FBI file (which states that he’s possibly a homosexual), there is no mention of his queerness. Although an argument can be made for time constraints, it’s a rather glaring omission in a film that deals in nuance and multilayered critiques. Baldwin’s sexuality was as much a part of his canniness and oppositional stance as his blackness; so while I Am Not Your Negro remains an astounding statement about race, a sequel that makes his queerness visible is sorely needed.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.