For many fans, Elvis Presley will indeed continue to be The King, but which Elvis do they hold closest to their hearts? The youthful, hip-swinging, Sun Records rockabilly Elvis? The leather-jacketed ’68 Comeback Special Elvis? The gleaming Technicolor Elvis of so many turgid movies? The Vegas Elvis, with rhinestone-encrusted jumpsuit and karate asides? Whether parent-scaring rebel, US army recruit or porcine casino attraction, Elvis remains both ubiquitous cultural icon and unknowable enigma, which somehow makes Eugene Jarecki’s sprawling, agitated and hard-to-pin-down combination of musical biography and state-of-the-nation think piece a curiously appropriate mode of address to consider the current state of the Presley legacy.

Germany/USA 2017

107 mins approx

Director Eugene Jarecki

Cast

Himself Alec Baldwin

Himself Ethan Hawke

Himself Chuck D

UK release date 24 August 2018

Distributor Dogwoof

thekingfilm.co.uk

► Trailer

The sincerity and ideological engagement seen in Jarecki’s previous feature docs Why We Fight (2005) and The House I Live In (2012) are present again here, though the canvas is wider. This film is literally all over the place, as a 1963 Rolls-Royce once owned by the star is pressed into service so that Jarecki and an ever-changing roll call of guests and passers-by can drive it around key places in the Elvis story, from Tupelo to Memphis, New York to Hollywood; interspersed throughout the journey are aerial views of this big and complicated country. Meanwhile musicians play their guitars on the back seat, and actors including Ethan Hawke and Alec Baldwin say their piece. There are friends who actually knew Elvis, plus key music critics Greil Marcus and Peter Guralnick, all reflecting on the awful tragedy of Elvis’s success. There’s a boatload of choice archive too, capturing the King and the country through the decades. And yet, for all the abiding sense that Jarecki has just kept shooting and shooting, there’s an underlying purpose here, implying that the meaning of Elvis is the meaning of America itself.

On one level, this relentlessly buttonholing, sincere and slightly exhausting film reminds us how Elvis exemplifies the endless capacity for division to be found in these so-called United States. Guralnick, for instance, is typically lit up by the way the young Elvis took the earthy thrust of rhythm and blues and fused it with a country twang to sell it to the white mainstream audiences who weren’t tuning in to the part of the dial playing ‘race music’ on the segregated airwaves of 1950s America. For black cultural commentator Van Jones, on the other hand, Elvis remains the very devil of cultural appropriation, who stole from essentially African-American forms and made a pile of money but put nothing back into the black community. He is echoed by former Public Enemy mainstay, the ever-articulate Chuck D, who repeats the salient line in the rap outfit’s signature number ‘Fight the Power’, declaiming: “Elvis was a hero to most, but he never meant shit to me.” That said, even he admits that the possibility of crossing cultural boundaries – choosing the example of a classical musician from an African-American background – is still something worth celebrating in today’s America.

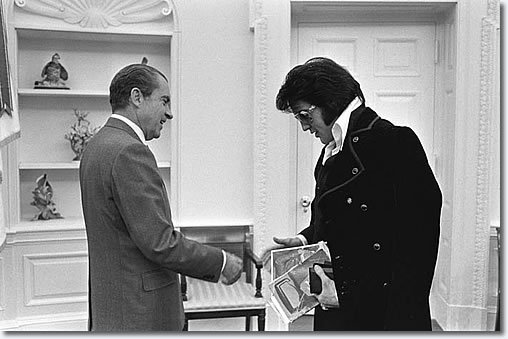

Chuck D in The King (2018)

To Jarecki’s credit, he gives the debate over cultural appropriation due space, but knows there’s more to say. In the meantime, even if it’s slightly overrun by the myriad moments of performance and on-the-road local colour, a grand theory of Elvis-as-America does emerge. It springs from Marcus’s telling insight that the American constitution makes a point of mentioning ‘the pursuit of happiness’ – a pursuit that codified itself in the resurgent post-WWII US into an ongoing spiral of consumption and display. However much we decry Elvis’s dollar-driven career choices, as Ethan Hawke bitterly points out, they trace a trajectory from dirt-poor beginnings, where his dad landed up on a chain gang for bouncing a cheque, to the son’s eventual cash-rich accumulation of a much flaunted fleet of cars and a gold toilet. Has America, then, like Elvis, simply consumed itself into a state of dazed, self-involved bloat?

Broadly, Jarecki would have us believe that the Trump presidency represents the fat, doped-up, dead-on-the-toilet stage of America’s national journey. A partisan view, of course, and as such very typical of today’s highly polarised US electorate. Baldwin, filmed in 2016 (!), calls it wrong when he vehemently insists that Trump won’t win the White House, but his assertion elsewhere that the ‘greed is good’ shift of the Reagan era forever changed the American landscape rings dismayingly true.

Given the horrifying contrast between beautiful young Elvis and his hulking 42-year-old corpse, it would be understandable if this ambitious, deeply felt undertaking finally surrendered to despair, yet Jarecki gathers himself for a final flourish. A punchy montage intercuts his country’s recent historical careen with a majestic late-Elvis TV-special performance of Unchained Melody – his vocals a keening, heartsick expression of yearning for redemption and deliverance, even as the end is looming. In America too, it seems, perhaps the hope for something better is not yet totally extinguished. Not while Eugene Jarecki is around to give us a film as mesmerising, contrary and complex as Elvis himself – or indeed the country that spawned him.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.