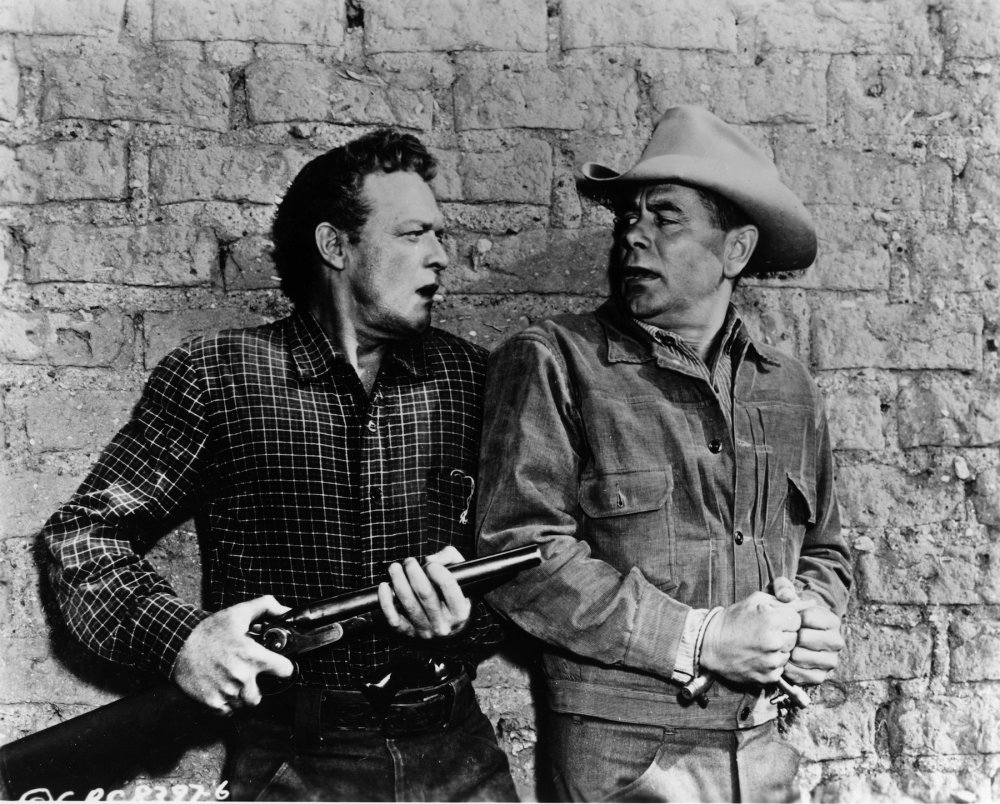

Van Heflin and Glenn Ford in 3:10 to Yuma (1957)

Adrian Wootton: It’s a great pleasure to welcome our very special guest this evening. Just the format — very obviously — we’re going to show you 3:10 to Yuma. There’s literally going to be a five-minute break while we do a little bit of stage set-up, so you’ve just got time then to pop out to the loo and then come back when we’re going to have an onstage interview with Elmore Leonard, our special guest of honour. He’ll be talking to me for a little while, then I’ll open it up to you to ask questions. My only other bit of housekeeping is that if you have a mobile phone, please switch it off now.

And whilst you’re just doing that I’d like you to give a very, very warm welcome because it’s fantastic that we have Elmore Leonard over here for the first time in nine years. The last time he was here I interviewed him in 1997. It’s fantastic he’s come back to the National Film Theatre and effectively you’ve got a bit of double-Dutch tonight, because not only is he going to do the interview but he’s also very kindly agreed to introduce 3:10 to Yuma to you. So ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Elmore Leonard.

[applause]

Elmore Leonard: Thank you. Thank you. 3:10 to Yuma appeared originally in Dime Western magazine. It was a 45-hundred-word short story and Dime Western was one of the prestige cult magazines at the time. And they paid two cents a word, so I got $90 for 3:10 to Yuma. And it sold almost immediately to Columbia Pictures. And they offered $4,000 and no-one else was offering anything so we sold it to Columbia. But then it took them about three years to get it into production.

And the $4,000… 25 per cent of it was claimed by Popular Publications, which owned Dime Western — Dime Western by the way was a quarter… and I was very happy in the 50s to sell to anyone, but especially to Dime Western because it was the pulp magazine. 25 per cent of it went to Popular Publications and I ended up with about $25 hundred.

Now, however, Columbia is going to make the picture again. They want to make it again with the director who directed Walk the Line [James Mangold, 2005]. And Tom Cruise is in line to play the Glenn Ford role and Eric Bana the guy who is going to take him to Yuma, if he can get him there.

I’m sure that the new version will be changed quite a bit. Tom Cruise, I’m told, is asking for rewrites… you know, that’s Hollywood, that’s what happens out there. I’m glad I’m not a screenwriter, I’ll tell you. Maybe… I don’t know why Tom Cruise wants to do this particular picture… I don’t think he is signed yet but they seem awfully anxious about it and I think that… they appear that… he will do the picture though it hasn’t been a go quite yet.

The picture… it was the first movie that I sold, but it was the second one to be released. There was another Western called The Tall T [1957] that appeared in Argosy magazine, and Randolph Scott starred in that with Richard Boone as the bad guy. And that came out first I think in ‘55 or ‘56, and then 3:10 to Yuma in ‘57.

Now I was very pleased with it. They had to add about 20 minutes to a half hour onto the front end of the picture because a 45-hundred-word short story isn’t going to get you very far in a feature. However they did fine, they did a good job in adding on and I was very, very pleased with the picture. And… let’s watch it, alright?

[Screening]

AW: Ladies and gentlemen. Welcome back to part two of this very special event in the NFT’s Western series. Before I welcome Elmore Leonard up on stage, we’ve got an extra little treat for you, which is a little… a very short clip of one of my favourite adaptations of an Elmore Leonard Western, which is Valdez Is Coming [1970]. So we’re going to show you a little clip of that and then I’m going to welcome Elmore on stage. So enjoy this little bit from Valdez Is Coming. Thank you.

[Clip]

Burt Lancaster in Valdez Is Coming (1970)

AW: Well, welcome back to the National Film Theatre. It’s lovely to see you back here after nearly a decade… and here, particularly because of our Western season. So I’m going to start by asking you a bit more about Westerns and then I’m going to open it up to the audience to ask you some questions, which I am sure will be about everything in terms of your very distinguished and prolific career.

Let’s carry on from where you started, talking about 3:10 to Yuma. You started telling stories to prestigious pulp magazines like Dime Western. Why did you choose the Western as the genre that you started writing for the pulps, because there were all kinds… I mean there was science fiction, there were crime pulps all at that time — why did you particularly decide to start submitting stories for Western magazines?

EL: I liked Western movies. And that was my aim to get going, to sell some stories and then hope that they would be adapted as films. And this one was the first one, in 1953. 3:10 to Yuma was probably the fourth or fifth story that I had written and that year I wrote my first book, The Bounty Hunters… That was not my ending with Glenn Ford pushing the good guy onto the train. It was the other way around. But that was a Hollywood ending, you know, where the star has to redeem himself in the end.

AW: But in terms of Western movies, which… I mean what were the influences on you at that time? What Western movies were you looking at that influenced you? And were there other Western writers, were there Western novelists that influenced you? Or was it non-genre writers?

EL: There probably were a couple. Ernest Haycox was a good Western writer. Luke Short was very, very popular. I thought he was all weak though, he always had to have… he had to have a comic relief. He had to have like a Gabby Hayes, you know, someone like that, and I never had that.

I would… my books were always turned down by Saturday Evening Post and Colliers because they were too relentless. They were one line, you know, they would just drive along. And I didn’t have… there weren’t any interludes where the… like his wife. His wife was not in my short stories. There was no room for her. I thought Leora Dana though was awfully good.

AW: It’s a very good movie, isn’t it?

EL: I was surprised we didn’t see more of her after that. She was good.

AW: But Glenn Ford is still with us.

EL: He’s 80 years old, yeah.

AW: And he did — I was thinking about this in terms of the Westerns — he appeared many years later in a TV adaptation of one of your Western stories. Because a few of the Western stories have been adapted for TV many years later…

EL: Yeah, he… I never saw that one, I don’t know what is was… probably… I think it was the second book.

AW: Last Stand at Saber River or something like that.

EL: Well, I don’t remember, no. I met him in Telluride and I was on the stage with him and the interviewer, Roger Ebert, but he had no idea who I was. And he got hold of the mic and wouldn’t let it go. [laughter] He wouldn’t give it back. So that was that.

But I told him… I said you know that when we saw Gilda [1946], we all — and this was right after High School — I said we all buttoned our sport coats the way you did in Gilda with… he would button the top two buttons, you know, we thought that was pretty cool.

AW: But did you have — you were selling stories to different magazines, you were fortunate enough to start having them bought for the movies — but did anyone at that stage, you know, contact you about the stories? Did the studios… or was it just purely a deal through your agent and you had no involvement at all?

EL: No, it was strictly someone read the story and decided it would make a good movie. No, that was it. Hombre [1966] was pretty much the same way. It was a husband-and-wife writing team that got the producer interested and I remember them writing to me and saying ‘we’re interested in reading more of your material, that maybe lightening will strike twice.’ Well I didn’t think of it as lightening at all. I just thought of it as work, hard work and aiming for the screen.

AW: But Hombre, directed by Martin Ritt and starring Paul Newman in ‘66… am I right in thinking that that… that gave you a financial stake that allowed you to stop doing all the other things you’d had to do and concentrate on writing full time, is that correct?

EL: Well, it was the opportunity… although they only paid $10 thousand for the screen rights. I wasn’t making much money then at all. Not until Valdez Is Coming. That jumped me up and that was a great relief when I sold that one. And the producer wanted to get… oh I forgot who it was now… to play opposite Burt Lancaster… oh Marlon Brando… Marlon Brando and he wanted Marlon Brando to play the Burt Lancaster part. But Brando wouldn’t do it because he had to shoot… his background in the story was that he had been a scout and he had shot a lot of Apache Indians. So he wouldn’t go for that and so they said well we don’t need you. [laughter]

AW: But it’s interesting because in this — and I heartily recommend this, published by Orion, this is just coming out, a collection of all of Elmore’s 30 Western short stories — and it has the original version of Valdez Is Coming, because am I right in thinking that Valdez Is Coming started life as a short story, which, I think — and it’s the only example that I am aware of in your career — where you took one of your short stories and then expanded it into a novel.

EL: Yes, you’re right, you’re right. I remember expanding it. I wrote the book in three weeks and that’s… or five weeks… but it was a very short period of time. And I remember I called H.N. Swanson, an agent in Hollywood, and I said ‘I’ve got something that I know is going to be a movie.’ I said ‘if you get a producer in your office I’ll come out and pitch it and I’ll bet you anything he’ll buy it.’ And he said — Swanny said — ‘send me the story’ which I did and he sold it immediately.

AW: And was he — I get the impression, because there’s a picture of him on your website — I mean he was a legendary agent, because he was Raymond Chandler’s agent wasn’t he? And…

EL: He was, yeah.

AW: …lots of great crime writers’ agent. Was he a very important person in your career?

EL: He was. He was a lot of fun, I’ll tell you, because he would buy things… I mean he would sell things for as much as you could get up front and forget about the back end, forget about what you might make eventually, you know. He was just a good guy, he was a lot of fun.

The story is that Raymond Chandler called him to be represented and Swanny said ‘well, where are you?’ He said ‘I’m at Warner Brothers. I’m making 150 a week’ and Swanny said ‘I don’t represent any writers who make 150 a week.’ So he called up Warner Brothers — the story goes — and got him raised to 750 a week. I don’t know, it could be true because it’s a wacky town, you know. [laughter]

Because they think… like the first screenplay that I wrote, which was The Moonshine War [1970], and I went out to Hollywood to rewrite it — naturally you have to do that — and Swanny said ‘how much do you want to rewrite it?’ I said ‘well, I don’t know, what do you think?’ He said ‘well, how about $25 hundred a week?’ I said ‘well, what about 35 hundred?’ So then he called MGM and it was Marty Ransohoff who was… you know he was… just saying his name… Marty Ransohoff. Marty Ransohoff went for it because now he’s got a $35-hundred-a-week writer… [laughter]

AW: But even though you switched largely, after Valdez Is Coming, to start writing crime novels, you didn’t really give up the Western during the 1970s and 80s because you actually — also as your career developed as a novelist, but also as a screenwriter — you kept on writing Western scripts. And I wonder if you could talk a little bit about them, because particularly I’m thinking about your relationship with Clint Eastwood on Joe Kidd [1972], and I think you wrote Mr. Majestyk for him as well, originally.

EL: Yes I did and…

AW: Could you tell us a little bit about that?

EL: I thought he was going to buy Mr. Majestyk. It was… because he called me up and said… and one of my children — they were all younger then — he answered the phone and I remember my son saying ‘Dad, it’s Clint Eastwood’ and then everybody ran for a phone. [laughter] And by the time I got to the phone I could hear them fighting on the extensions, you know. And Eastwood said ‘I need a story, I need something like…’ what was the first one he did with the big gun, er…?

AW: Dirty Harry [1971].

EL: Dirty Harry. He said ‘I need something like Dirty Harry only different.’ They always say that. ‘I need something just like that, only different.’ Now he could be anything but he carries a big gun, because he didn’t own enough of Dirty Harry to make him rich then.

So I then… that night I got the idea for Mr. Majestyk and called him the next day and told him, and he said ‘good, work it up.’ So I worked it up and went out to Hollywood on something else and I went to see him, and I felt sure he was going to buy it and do it. But by then he had acquired High Plains Drifter [1972], which he really liked a lot. And Mr. Majestyk … I don’t know, I thought it was okay, but then Charles Bronson got a hold of it and Walter Mirisch — who now has become a good friend of mine — he produced the picture.

The Mirisch Corporation did a lot of good movies and Bronson… in fact that is still making money, I still get residuals on Mr. Majestyk… it could be $43, it could be $4,000, you never know how much it’s going to be, but it means that it’s sold somewhere, you know, and I would get 1.4 per cent of the gross on any kind of additional sale. 3:10 to Yuma… Charles Bronson… I was a little sceptical about Bronson because when he’s delivering dialogue he always hits the wrong word, you know? And I don’t understand that. [laughter] It seems so obvious…

Clint Eastwood and Robert Duvall in Joe Kidd (1972)

AW: But going back to Joe Kidd for a sec, there was another story, you said, that told you an awful lot about stars with Clint Eastwood, and wasn’t there something about Clint Eastwood and a gun in Joe Kidd…

EL: Oh, in Joe Kidd, yeah. That was not my title. My title is The — oh… The something War… I forgot — but he decided to do it and he got John Sturges, and John Sturges had just done — well maybe a couple of years before he did — The Magnificent Seven [1960]. And he was so in love with The Magnificent Seven, he was using outtakes from that picture in Joe Kidd.

And he didn’t like the way the plot went. He didn’t think that John Saxon should be the bad guy. Well, who’s the bad guy? So he mentions somebody who worked for John Saxon, you know, one of his gunmen. But you don’t know what he looks like, you don’t know… he’s the guy who’s causing all the trouble but we haven’t met him yet. All he is is a name, and names don’t mean a thing in movies, you know. So I didn’t think the picture worked at all. And he… there were so many dumb things about the picture but what can you do? Nothing. So…

AW: But going back to Valdez Is Coming, it’s interesting in terms of the development of your career… I mean a lot of people talk about what a really marvellous book… in fact George Pelecanos said… I was reading something where he said it was his absolute favourite books of yours. Do you think that Valdez Is Coming was one of the important books in your career in terms of where you began to find your real voice as a writer?

Because people talk about how… you know the Elmore Leonard style, based on character and language and dialogue, and it seems to me that the novel certainly — and to a certain extent the film of Valdez Is Coming — has got… it has got that model for the kind of Elmore Leonard laconic hero, the man who actually doesn’t do a lot of shooting, he does quite a lot of talking in a very witty and quite ironic way. Would you agree that Valdez Is Coming was quite a seminal book in your career?

EL: Well, certainly it came at a good time, yeah. But I didn’t… I thought that Burt Lancaster… I didn’t like the way he was made up. He had a lot of Max Factor all over his face and I didn’t… I don’t know why… they could have done a lot better with a character actor, you know? But he wanted to do it and it probably made more money because he did, but I thought they could have done better.

AW: In terms of writing Westerns, obviously you largely stopped in the early 70s, but you have periodically returned to write the odd Western story. You wrote Gun Sites in 1979 and there’s a couple of stories here, one from 1982, The Tonto Woman, and one from the 90s. Do you still hanker to write Westerns? Is it something that still appeals to you?

EL: There’s not that much of a desire… they all say ‘we really want to do a Western’ but for some reason they don’t, you know. Why does Tom Cruise want to do a Western? I’ve no idea.

AW: You like writing them though?

EL: No. I don’t… oh yeah, I like writing them, but I’m not going to write another Western novel because I don’t think there’s enough market for it. I’ve always gone for markets. I want to sell and make some money when I’m going to do this.

AW: It makes absolute sense.

EL: I write as well as I can but still… let’s make out. [laughter]

AW: My last question on Westerns…

EL: I think though that The Tonto Woman could be a movie, could be a good movie. It’s a story about a woman who was captured by Tonto-Mojave Indians and they tattooed her face with purple lines — both cheeks and her chin — and she finally is brought back, she’s rescued and she’s married to a rancher who got rich while she was captured by the… taken by the Apaches and he puts her out in a lime shack way out on a prairie… out in a pasture somewhere and then just delivers food to her from time to time, until this Mexican comes along who’s going to steal all the guy’s cattle — or as much as he can — and he sees her and something starts to… a story starts to develop. And I think it could be a really good movie if any actress in Hollywood wants to play it with her face… with all these lines painted on her face… tattooed on her face.

AW: It’s a great idea. I can’t see too many Hollywood actresses doing that.

But in terms of the movies, you’ve had an awful lot of experience in the screen trade — ups and downs, seeing… both adapting your own work, writing for other people, seeing lots and lots of movies made — and obviously that informed Get Shorty [1995] and you drew on that experience for Get Shorty.

Why do you think, though, it took so long — with odd exceptions — why do you think in terms of your crime novels that it took so long for people to get it right? I mean, in terms of Scott Frank with Out of Sight [1998], which we’ll see a clip of at the end, and Get Shorty… there’s been a period in the — and of course Quentin Tarantino with his adaptation of Rum Punch: Jackie Brown [1997] — why do you think Hollywood misunderstood for so long your work?

EL: I didn’t sell my novels successfully until ‘85. You know, I’d been a writer for more than 30 years. Finally I got on the New York Times list and the first time I was on for about sixteen weeks… because people wanted to… they’d heard all about me so now they wanted to read the book and find out what it’s about.

Well then the next time I was on the list, maybe I was on for nine weeks and then it kept going… the last book, The Hot Kid, was on for two weeks but it was on at a very bad time when there were too many substantial writers who are consistently in the top slots. I didn’t think that I would ever get on the New York Times list because I never thought that I wrote well enough or poorly enough to get on that list. [laughter] So…

AW: But going back to the question, in terms of… what do you think Scott Frank, for example, brought to it as a scriptwriter that so many other writers and directors have missed before? Do you think he had a special understanding of your work?

EL: My stories I think are very simple and should be very easy to adapt. Scott Frank says that he reads the book the first time very quickly, just to find out what it’s about and then he reads it again very slowly to find out what the theme is. And then he tells me what the theme is and I say ‘really? I didn’t know that. I thought I was just writing a book.’ You know, I don’t think of theme. What is a theme?

Well he said ‘you know, what Get Shorty is about,’ he says ‘it’s about old people in Hollywood and how they… what they have to contend with to make it.’ Well. I didn’t know that. But it is a young, young industry, you know. I have no business writing screenplays at my age. They… I don’t… because just the fact that I’m twice as old as they would consider anyone writing a movie.

AW: Well, it’s a good job they can’t do that with novels.

EL: Well, I’m glad that I don’t… that I’m not a screenwriter. You know, I’d be… it would be so frustrating. You know, David Mamet said that backstory is for studio executives to have something to talk about. Where did this guy come from? What is he doing? How did he become a gangster? Well, he just is, you know. You don’t need to do any more than that. [laughter] He’s lazy, you know, whatever the reason…

Pam Grier in Jackie Brown (1997)

AW: But tell us — before I hand over to the audience to ask some questions — tell us a little bit about where that inspiration comes from in terms of… because you’ve been writing incredibly successfully now for many, many years — you still produce a novel a year or every two years — and you’ve managed to mine Miami, Detroit and all the other locations, but does your city still inspire you? Do you still get inspiration…?

EL: Well, I only wrote… I only set the stories in Detroit because I live there, not because it was the murder capital at any time. You know, 750 homicides in the late 70s, there were 400 last year. But there are fewer people now in Detroit. A lot of them have left town. 700,000 moved out in the late 50s. So I’m not… no, I have nothing against Detroit. Of course in Hollywood the first question is ‘you live in Detroit? Why would you live in Detroit?’ Well, that’s where I live, you know. It’s not that bad… I like it.

AW: But where does the inspiration come from now? You’ve had a long-time relationship with a researcher, Gregg Sutter, who goes out and mines bits of information and brings them back for you. But where do the stories come from? Because you…

EL: Well, that’s it. He doesn’t go out and give me ideas. I tell him to get me something on — right now for example — rationing during the war, and stamps — ration stamps for food and so on — and to find out something about if there were any… if there was a spy ring, a German spy ring in Detroit, because now I’m writing a book that’s set in ‘45, the very beginning of ‘45, about a couple of German prisoners of war.

They were in a serial that I wrote for the New York Times. It was fourteen episodes and at the very end of it, these two guys escaped. And the hero — who is the hero of The Hot Kid — he’s after them. He’s a Federal Marshal and he knows that they have come to Detroit, but it still takes him five months to get away from what he’s doing to go after them in Detroit. And so that in the meantime then, I build up… develop characters, German-American characters who are sympathetic to the Nazis.

AW: So it’s a sort of sequel to The Hot Kid then, in that sense?

EL: Well, it’s the sequel to the serial that was in The Times, but that was not a very pleasant experience because I had to pull back. I had to… my characters couldn’t talk as freely as they wanted to. You know, I said ‘this guy escapes from the camp every couple of months for a few days and then he comes back.’ They said ‘well, what’s he doing when he gets out?’ and I said ‘maybe he just gets out to get laid.’ And the New York Times said ‘this is a family newspaper, you can’t say that.’ And yet I’ve got a couple of scenes where they’re all sitting around smoking grass and there’s nothing wrong with that. [laughter]

AW: At this point I’m going to open it up for questions because we haven’t got that much time, because Elmore’s very kindly agreed to do a signing out in the foyer afterwards and I’m sure there are a lot of you that will want to get books signed. But I am going to open it up to the floor now. There’s a gentleman right there.

Audience member: [inaudible]

EL: Frankie Laine?

AW: What did you think of the music from 3:10 to Yuma?

EL: Well, at the time I thought it was great, except that I thought maybe there was a little bit too much of it. But Frankie Laine was big then, you know, yeah.

AW: Has anybody got another question. Oh, yes, I see you, it’s alright.

Audience member: [inaudible]

AW: It’s a question about Elmore’s dialogue and how he gets those wonderful rhythms of speech, and he’s got that incredible ear, which is so characteristic of his books. And did he get that from hanging out with a lot of low-lives?

EL: No. I quit drinking 29 years ago, so I don’t spend a lot of time in bars, but I have a good memory. And I do … I listen to people. I listen to the rhythm of speech, I suppose. And I don’t know why anyone couldn’t write the same kind of dialogue — any kind of writer who’s interested in dialogue — but it’s so important to me because I move my stories with dialogue and less narrative.

Everybody in the book might have a turn at being the point of view. I don’t want to be… have one guy the point of view. I don’t have a continuing character. That, I think, would be boring to me. But to have other points of view they have to be able to talk. And so they… in the first part of the book they’re auditioned. And if they don’t make it, you know, they could get shot early on… [laughter]

AW: You see that happening, Elmore.

EL: …if I need the character… otherwise they just don’t make it.

AW: We’ve got one here.

Audience member: [partially inaudible]… can we assume that Ernest Stickly is one of your favourite characters?

EL: Who?

AW: Bringing Ernest Stickly back in a couple of books… and you’ve done that quite a few times.

EL: Because I did a sequel to Swag… no it was Stickly, oh Stickly?

AW: Yes.

EL: Yeah, I thought he was a good character so I brought him back and, of course, Chili Palmer… I brought him back because MGM said, walking out of the premiere of Frankman Cue says ‘well you can write a sequel to it, can’t you? Yeah. Well now Chili Palmer sued me. So I’m not going to write any more Chili Palmer.

AW: He sued you?

EL: Yeah. He was sick and he needed money. [laughter]

AW: Okay. You heard it here first. There’s no more Chili Palmer novels. The gentleman there…

Audience member: I want to ask… the first novels are set in Florida and then I think you moved to Detroit…

EL: It was the other way around.

AW: Yeah, they started in Detroit and then they moved to Florida and then came back.

Audience member: So it seems that Detroit and Florida are the extremes that he deals with… would you make a novel now set in Florida?

AW: Would you set a novel now in Florida, is that your question?

EL: Another one? I don’t know, I’ve set them in Los Angeles, in Atlantic City, in New Orleans…

AW: This one’s in Oklahoma isn’t it, The Hot Kid?

EL: Yeah, Oklahoma. I like Oklahoma a lot, you know, because it’s right in the middle. It’s very American.

AW: Anyone else? One there…

Out of Sight (1998)

Audience member: What motivates you to carry on writing?

AW: What motivates you to carry on writing?

EL: It gives me great pleasure. I get more satisfaction out of writing a scene that works… and I read it and it works and I have to smile. Reading it… there’s nothing better. I look at the clock while I’m working and it’s three o’clock, say, in the afternoon and I think ‘good, I’ve got three more hours.’ That’s the kind of job to have, you see.

AW: Gentleman there.

Audience member: I was wondering if you have ever thought about, say, producing, taking greater control of your novels, making them even better adaptations, control over the director and casting, and things like that.

EL: No. If I were to take control as a producer, you know, so that the adaptation would be closer to the book… but that’s not what I do. No, I don’t want to get into the business of it, no, not at all.

AW: Another, yes, over there.

Audience member: [partially inaudible] Do you see actors and filmmakers who are inventing your characters … I just wondered if it helps you write seeing certain actors playing the parts?

AW: Do you imagine people characters with actors’ faces?

EL: Well, I will see a supporting actor, a good actor, playing a part but never the star. I never see a star. I don’t think of stars in my stories because I try and see real people. I don’t even see them clearly. I don’t want to see my characters clearly. I don’t want to describe them that way, in detail, because I want the reader to see the character, imagine the character the way he or she wants.

AW: We’ve got one at the back there, yes.

Audience member: How much planning do you do for your stories? Do you know how they are going to pan out? Or do you sort of feel the way?

AW: Planning that you do…

EL: No, I start with a situation and a character and add characters and make it up as I go along. And I get to… or I finish by seeing page 100 or 120, everyone has been introduced, pretty much. And then, okay, well let’s get them on. The middle part is the difficult… we’ve crossed lots of soil. I get to page 300 in my manuscript and I look toward the end to see how it’s going to end. I have no idea how it’s going to end. But there are always enough ways to end a book. You know, just pick the one that you like the best. [laughter]

AW: You’ve always done that, I know. In the past you used to write in long hand and then you used a particular typewriter. Have you never shifted to a word processor or are you still writing in long hand?

EL: No, I still write it with the Pilot V5 Precise pen, I think that’s what they’re called. Ten people sent me all of their pens. And I wrote a line with each pen and then sent it back to them … ‘this is the line’. And then they sent me seven of them because they said ‘just have them and write 14,000 words or something like that. So, your books are about 85,000 words and then that will string out to about that… so you need about six or seven pens.’ [laughter]

So. And then I… but I do have an electric typewriter now and I write and then put it on the typewriter to see what it looks like. And no, not a word processor because… someone would say to me ‘you don’t use a word processor? You can write so much faster.’ You know, as if speed had anything to do with it. [laughter] How about ideas, does it give me ideas too? No, just speed. I told that to André, the producer, one time and he just about fell off his wheelchair laughing.

AW: Time for one or two more questions. Somebody right over there.

Audience member: Do you like to be involved in adapting the work for the screen?

EL: No.

AW: No, okay.

Audience member: Killshot is coming.

AW: Killshot … well we actually have the director of the adaptation of Killshot in the room: John Madden just sitting over here. So…

EL: Where is John?

AW: John’s just right here.

EL: Where?

AW: Just there: John, in blue, he’s waving.

EL: Oh, no, I don’t have anything to do with the adaptation, no, and I certainly don’t want to write them, so… No, it’s not what I do. I thought at one time it would be fun but it’s not. It’s not fun.

AW: Well, I’m going to take one last question because we have to stop because we’ve got… there’s a gentleman there and then there’s somebody over there, so okay, maybe two quick… the gentleman there and then I’ll come over to you.

Audience member: [inaudible]

AW: Have you ever had a book come out and thought ‘damn, I wish I’d used another ending for it’?

EL: There are two books that I featured the wrong character — main character. No, I don’t know… I doubt that anyone really noticed, but I think they would have been better books if I had stayed with the characters I started out with… but shifted over. One of them was set in Israel, it’s called… The Hunted.

AW: Yep.

Audience member: Why did you prefer to watch 3:10 to Yuma rather than The Tall T?

AW: Why did you prefer to watch 3:10 to Yuma tonight rather than The Tall T?

EL: You were going to show The Tall T. But I thought 3:10 to Yuma… because it’s going to be remade with Tom Cruise it would be interesting to see it, the original. That was the main reason.

AW: And The Tall T is on a couple more times this month at the NFT for those of you who haven’t seen it in a long time or have never seen it at all, I’m pleased to say. I am going to stop here because we, as I say, we’ve got a book signing, and also High Noon [1952] is on here. And for those of you who don’t know, Elmore actually once wrote a sequel to High Noon. I think it was High Noon Part II, in 1980.

EL: Oh man. [laughter] Hey, you’re defeated going in. You can’t do a sequel to High Noon, that’s it, you know.

AW: Well, we’re going to have the opportunity to see the original and we’re going to stop now, but I’d like you all to put your hands together for our very, very special guest of honour, Elmore Leonard.

[applause]

EL: Thank you.

AW: And if you could just stay in your seats for a minute or two because we’re going to end now on one of my favourite clips from a wonderful adaptation, Steven Soderbergh’s Out of Sight… a certain sequence with two very famous people in a car boot. So stay in your seats. Thank you very much.

[applause]

[Clip]

Interview © Elmore Leonard and the BFI 2006