1919:

Broken Blossoms

Director D.W. Griffith

One behemoth bestrode the 1910s, effectively siring narrative cinema at the scale we know it today. In 1915, D.W. Griffith’s most famous – and most controversial – epic, The Birth of a Nation, had taken in a million viewers just four years earlier. A smaller production in every sense, Broken Blossoms stands the test of time far better than the ugly politics of its predecessor, and, astonishingly, was just one of nine films that bore its director’s name in 1919 alone. That’s two more than Ernst Lubitsch, whose biographical romance, Madame DuBarry, stands as the other big contender for best of 1919.

A shattering love story between a Chinese immigrant and a destitute young girl in London’s Limehouse district – “A tale of lovers; a tale of tears” – Broken Blossoms might just be Griffith’s masterpiece, even while often viewed as an apologia for Birth of a Nation’s overt racism. It’s more complex in its critiques than such facile readings might suggest, all the while wrapped in an achingly beautiful melodrama that nimbly skips past sentimental to touch the sublime.

1929:

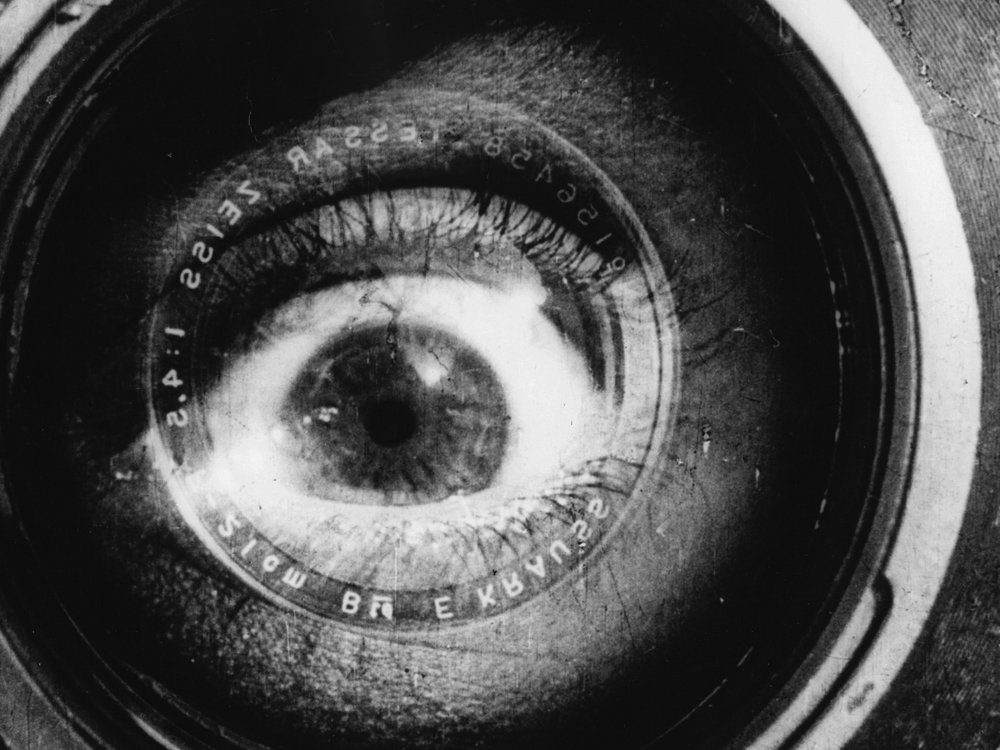

Man with a Movie Camera

Director Dziga Vertov

While there’s a tough choice to be made between the two films that catapulted Louise Brooks to superstardom, with G.W. Pabst directing both Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl in 1929, there’s an even bigger one to be made between a pair of hugely influential experimental films from the same year. Given just one 1929 pick, it’s nigh-on impossible to choose between Luis Buñuel’s surrealist wonder, Un chien andalou, and Dziga Vertov’s monumental documentary, Man with a Movie Camera.

Sight & Sound’s once-a-decade poll of the greatest films of all time saw Vertov’s leap into the top 10 back in 2012, making it the highest placed documentary on the list. “This film is an experiment in cinematic communication of real events,” read the opening titles, “Without the help of a story, without the help of theatre. This experimental work aims at creating a truly international language of cinema based on its absolute separation from the language of theatre and literature.” Seen today, especially on the big screen, 90 years after its theatrical premiere, Vertov’s film makes its case with vital, thrilling immediacy.

1939:

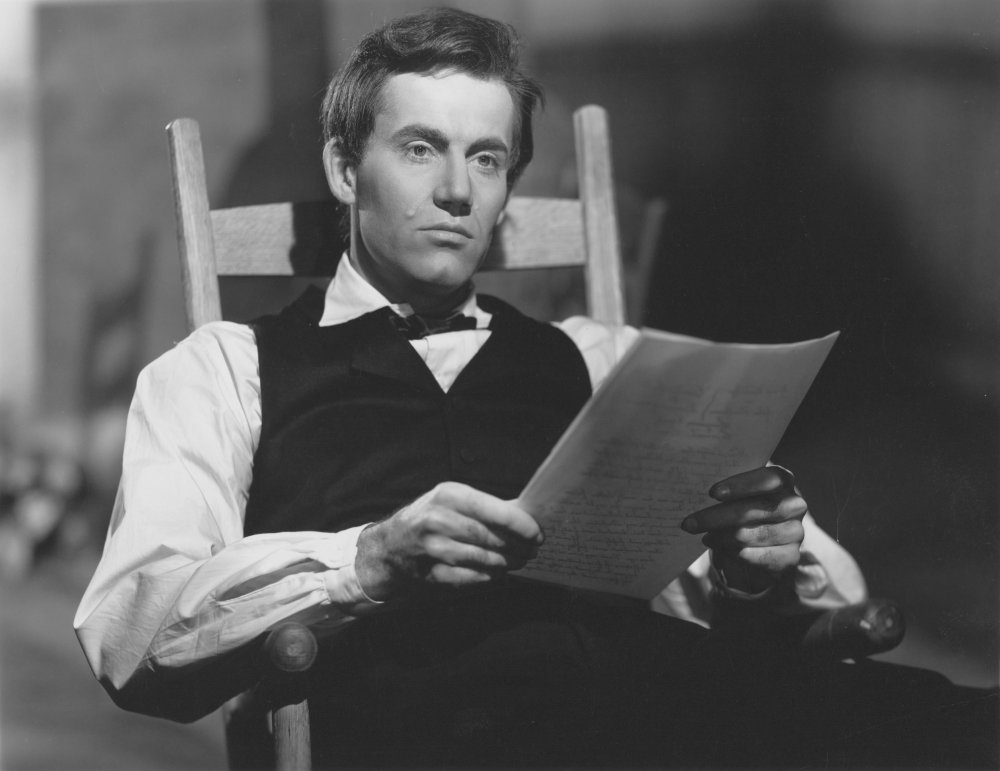

Young Mr. Lincoln

Director John Ford

What a year for cinema! 1939 played host to a number of films that could take the representative top spot. The Academy went with Gone with the Wind, anointing Victor Fleming’s civil war epic with eight Oscars, including best picture. Sight & Sound’s 2012 poll gave the honours to Jean Renoir, whose La Règle du jeu placed fourth. Cannes was an interesting one: with the festival cancelled due to the outbreak of war, it wasn’t until 2002 that a special jury was convened to award the top prize to Cecil B. DeMille’s Union Pacific, 63 years late.

It’d also be pretty hard to argue with the likely popular choice, Victor Fleming’s eternal The Wizard of Oz. Quite the year for Fleming, but our choice for 1939 went one better. John Ford released three magnificent features across the 12 months: an iconic star-maker in Stagecoach, a revolutionary actioner in Drums along the Mohawk and a hymn to charm and dignity in Young Mr. Lincoln. Ford was the pre-eminent myth-maker of American cinema throughout his career, and they come no more essential than those spun by Henry Fonda’s president-in-waiting.

1949:

Late Spring

Director Yasujiro Ozu

Another great year for John Ford with the release of She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, but there’s really no contest when it comes to choosing a film for 1949. Tokyo Story (1953) may still be the most recognised and revered of films by Japanese master Yasujiro Ozu – the Sight & Sound poll currently has it as the third greatest film of all time – but Late Spring is every bit the emotional wrecking ball of its better-known sibling.

The first part of the so-called ‘Noriko trilogy’, named after the character played by Setsuko Hara in all three films, Late Spring finds her in her late 20s, still living at home with her ageing father. Everyone around Noriko is cooking up marriage plans for her, against her own wishes. Like much of Ozu’s cinema, it’s a deceptively gentle film, with a cumulative emotional force that creeps up to take you unawares. The resigned sigh of its final scene, as Chishu Ryu peels that apple, makes for one the great endings in all of cinema.

1959:

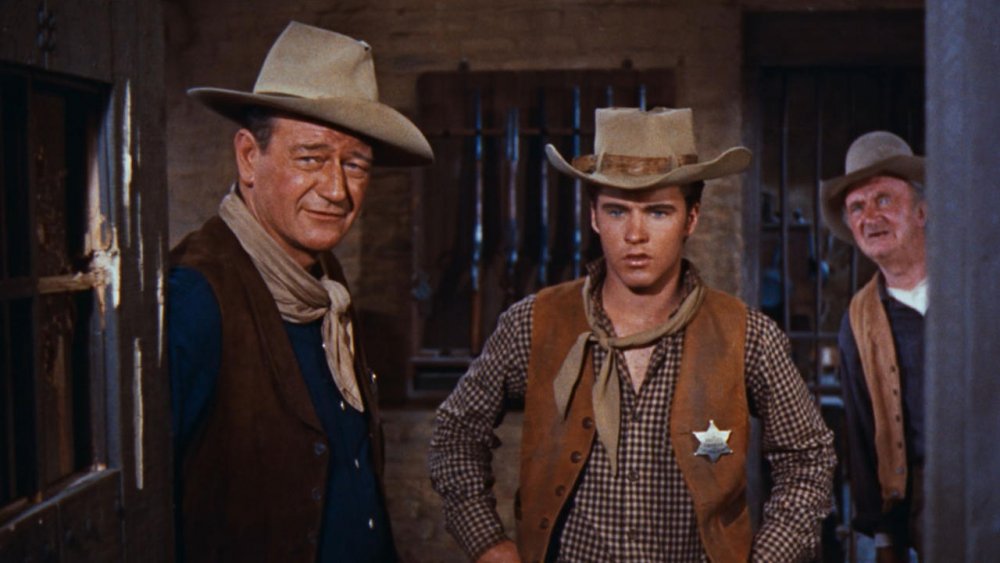

Rio Bravo

Director Howard Hawks

Another all-time-great year here. Check out this lot: North by Northwest (Alfred Hitchcock); Imitation of Life (Douglas Sirk); Anatomy of a Murder (Otto Preminger); Black Orpheus (Marcel Camus); Hiroshima mon amour (Alain Resnais); Nazarín (Luis Buñuel); Pickpocket (Robert Bresson)… You get the idea.

Even so, this was an easy pick for this writer. For all the thematic, formal and humanist riches of Howard Hawks’ larky western, we’re giving it the coveted ’59 slot simply for being so irrepressibly entertaining. Like much late-period Hawks, it’s a film you’re just happy to hang out with, moseying through its unhurried 141 minutes with the gang. Such is the lightness of touch, the warmth of its camaraderie, the songs at its heart – it all makes for pure, cinematic catnip.

1969:

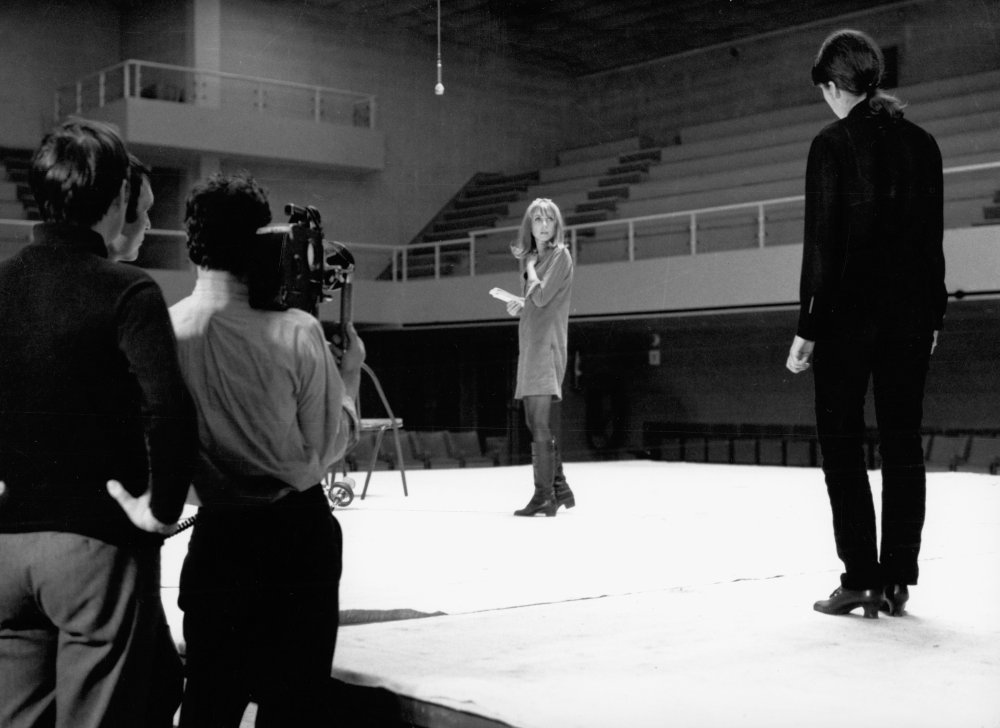

L’Amour fou

Director Jacques Rivette

In 1969, Tinseltown faced a sea change, as New Hollywood’s young turks charged in for some serious spring cleaning, finding major success with Easy Rider, Midnight Cowboy and The Wild Bunch. The international stage saw the likes of Boy (Nagisa Oshima), The Colour of Pomegranates (Sergei Parajanov) and The Cremator (Juraj Herz), but it’s to France we’ll turn for our pick of the year, at the end of a decade-long New Wave that changed world cinema.

By any standards, Jacques Rivette’s L’Amour fou is a tough proposition, not least due to its lack of availability. Now newly restored, it’s due to finally surface, taking its place on cinephile shelves next to Rivette’s magnum opus, Out 1 (1971). In many respects, it’s a natural precursor to that 13-hour marvel, clocking in at a much more digestible four hours. While difficult and experimental at first glance, there’s gold to be mined from Rivette’s multi-layered, theatrical investigation. The deep readings that’ll arrive with its re-release can’t come soon enough.

1979:

Apocalypse Now

Director Franics Ford Coppola

With best picture wins for The Godfather and The Godfather Part II (and best director for the latter), by 1979 Francis Ford Coppola was part of the establishment furniture. Madness beckoned, and swiftly came calling with a monster production outfit in the Philippines, where he decamped to bring Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness to the screen. The shoot itself became the stuff of Hollywood legend, the film’s commercial success unable to prevent nails being sharpened, ready to drive into the coffin of New Hollywood. Of course, the film is considered a masterpiece these days, placing 14th in Sight & Sound’s poll, and the war that was Apocalypse Now’s production is remembered mostly through Eleanor Coppola’s jaw-dropping documentary Hearts of Darkness (1991).

It was quite the year elsewhere too. Back in the States, Woody Allen released Manhattan, while 25 May saw the world premiere of Ridley Scott’s Alien. Further afield, Werner Herzog finished arguably his greatest film, Nosferatu the Vampyre, as his fellow-traveller in the New German Cinema Rainer Werner Fassbinder released another masterpiece in The Marriage of Maria Braun. Had we not gone the arthouse route for our ’69 pick, rest assured that ’79 would have been snatched from Coppola by Andrei Tarkovsky and his existential wonder, Stalker.

1989:

A City of Sadness

Director Hou Hsiao-Hsien

A new decade draws to a close, a new dawn for American independent cinema rises from the ashes of 80s excess, led by Steven Soderbergh’s Sundance smash, Sex, Lies and Videotape. By the time summer rolled around, audiences around the world were taking a blast of New York heat from Spike Lee’s incendiary masterpiece, Do the Right Thing.

We’re turning our attention east though, with a hope to inspire someone – anyone! – to release the greatest film from Taiwanese master Hou Hsiao-hsien on UK home video. Winner of 1989’s Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, Hou’s film tells of four brothers in Taiwan as the island is ceded back to China by the Japanese. At once epic in its scope and devastatingly personal, Hou’s nigh-on impossibly beautiful masterwork tells of a national tragedy in the most acute human terms, best personified in Tony Leung’s deaf Wen-ching. It’s a staggering achievement by any measure, and not screened nearly enough.

1999:

Beau Travail

Director Claire Denis

Its 20th anniversary this year has seen a lot of online chatter about how great 1999 was for cinema. It’s hard to argue with much of it, given that the end of the last century gifted us the likes of All about My Mother (Pedro Almodóvar), Magnolia (Paul Thomas Anderson), Time Regained (Raul Rúiz), Pola X (Leos Carax), Ghost Dog (Jim Jarmusch) and The Insider (Michael Mann), along with one final masterpiece from Stanley Kubrick in Eyes Wide Shut.

If it all sounds like a boy’s club, Claire Denis was on hand to set the record straight, delivering what was arguably the film of the year – perhaps even the decade – with her lads-on-tour-de-force, Beau Travail. A loose adaptation of Herman Melville’s Billy Budd, the film follows a group of legionnaires stationed in Djibouti. Denis captures the rituals of male and military bonding with an ecstatic eye for bodies and landscapes, floating with impressionistic grace and beauty towards the greatest dance sequence in all cinema.

2009:

Avatar

Director James Cameron

On 7 March 2010, a formerly married couple went toe-to-toe at the 82nd Academy Awards, both vying for best director and best picture. Kathryn Bigelow made history as the first female director to win the Oscar, The Hurt Locker taking the top award to boot. Unfortunately, for our purposes here, the film saw numerous festival outings at the tail end of 2008, which knocks it out of our list’s running.

With the sequels fast approaching, we can expect many a reminder of Avatar’s salad days as 2020 lands. Not that we really need it. For all the instantly-tired Dances with Smurfs gags lobbed its way, there’s no discounting the sheer technical heft of James Cameron’s opus – the most commercially successful film of all time until recently overtaken by Avengers: Endgame (2019). One of the great world-builders in cinema, Cameron has few peers when it comes to action staging. What else has come close to the orchestration of Avatar’s final hour in the decade since, besides Fury Road? Haters can hate away, but the smart money’s on never underestimating Cameron when his sequels breach the horizon.