French writer-director Céline Sciamma’s latest exploration of young female identity (following Water Lilies, 2007, and Tomboy, 2011) has been released with the international title Girlhood. This cookie-cutter title, while great for distribution, does a great disservice to a film that is much more defiant and unsettling than Richard Linklater’s subtle meditation on middle-class American suburban boyhood. This is no quietly incremental coming-of-age narrative, but a brash, at times distressing series of snapshots of the life of undereducated black working-class girls on the bottom rung of every social and economic ladder.

France 2014

Certificate 15 113m 25s

Director Céline Sciamma

Cast

Marieme/Vic Karidja Touré

Lady Assa Sylla

Adiatou Lindsay Karamoh

Fily Marietou Touré

In Colour

[2.35:1]

Subtitles

French theatrical title Bande de filles

UK release date 8 May 2015

Distributor Studiocanal Limited

► Trailer

Marieme and her friends are feisty, sassy, sometimes scary girls – beautiful, smart, funny young women, whose potential is always in inverse proportion to the opportunities open to them. They are girls whose lives and spirit are painfully held in check by the unspoken rules of flawed authority figures: uninterested teachers, absent mothers, big brothers, macho boys and petty bosses.

Their only defence – and the film stresses that it can only ever be a temporary refuge – is the aggressive solidarity of the bande de filles, or girl gang; the kind of antisocial, mouthy group you wouldn’t want to meet on a métro platform late at night. Less girlhood than girls-in-the-hood, the film has a lot in common with Mathieu Kassovitz’s blistering La Haine (1995), alternating in the same way between anger, frustration and hope, but without that film’s narrative reliance on macho props and posturing.

Girlhood (Bandes de filles, 2014)

The opening moments of the film set the tone for how the energies of Marieme and girls like her are constrained by the world they inhabit: a bruising game of American football is under way, the participants dressed like modern gladiators, their hard bodies armoured with padded shoulders, helmets and faceguards. They roar as they play, deafening us with yelling that segues into jubilant laughter as the game ends and the helmets come off.

Then these mighty combatants are revealed to be two teams of young women, energetic girls of every shape and size, revelling in the joy of their own strength. The noise continues in the form of raucous chatter as, high on adrenaline, they walk back in groups to their estate.

But the closer they get to home, the quieter they become; nearing a group of boys hanging out on their path, they lower both their volume and their heads, and suddenly the night is over. They peel off one by one from the group, intimidated, obedient, newly vulnerable, and return to their separate homes individually and in silence. It’s a sobering and impressively effective demonstration of the place of these girls in a world of intense social pressures, and of the liberating potential of female solidarity if only it can be allowed to take root.

Girlhood (Bandes de filles, 2014)

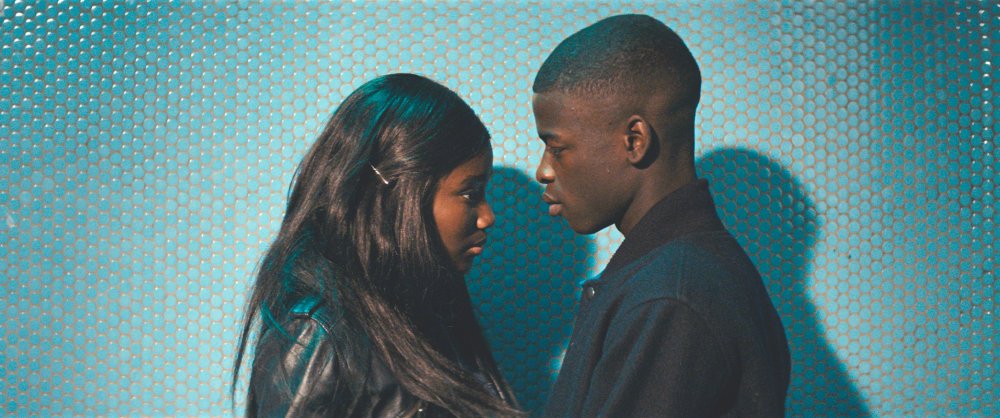

This potential is seen in all its glory in a number of set pieces once the film has united Marieme (now renamed Vic) with the stylish and super-confident trio Lady, Adiatou and Fily.

The first takes place in a hotel room in Paris where the girls, on the back of a shoplifting spree, hole up for a night of pizza and partying. Sprawling over the massive bed in a huddle of long limbs and hair, the girls colonise every inch of a space that is theirs and theirs alone for the duration of the night. Like kids left alone with a dressing-up box, they do each other’s makeup and try out the clingy dresses they have acquired, and dance and sing and strut for no one’s pleasure but their own. For one night only they are the stars of their own story, lip-synching to Rihanna’s Diamonds as if born to perform.

Later, in an outdoor scene at La Défense, they dance for the pleasure of an impromptu audience of other girls, delighting in the sheer beauty and energy of their own bodies. To see these same bodies stilled elsewhere in the film by violence and taboo is thus all the more agonising, whatever crimes and actions the girls may be guilty of.

Girlhood (Bandes de filles, 2014)

The film’s four main actresses were all non-professionals, scouted by Sciamma’s team in open casting calls in the shopping malls, train stations and working-class suburbs of Paris. Karidja Touré in particular is a revelation: Marieme/Vic appears in every scene but is always in the process of transforming herself via costume, hair and makeup, like the work-in-progress her character clearly is. Even before the film’s conclusion we can be no more certain than at any other point that her identity has been definitively fixed; indeed, we can only rejoice at the near escape she has had from the fixing that society would impose on ‘girls like her’.

-

Sight & Sound: the June 2015 issue

Girlhood and the faces of the new French cinema – plus Clouds of Sils Maria, The New Girlfriend, the Tribe, Phoenix and the S&S Interview with...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.