Autism has become a current generation’s “defining psychiatric malady”, Benjamin Wallace wrote in New York magazine in 2014 – a condition not only better understood and more diagnosed than in previous eras, but also applied and misapplied scattergun-fashion as shorthand for certain behaviours and traits, and even claimed as a status symbol by people who wish to be found more pitiable and exotic by others. A psychiatric diagnosis, wrote Wallace, has become “a conceptual gadget for processing the modern world”.

USA 2016

Certificate PG 91m 39s

Director Roger Ross Williams

[1.78:1]

UK release date 9 December 2016

Distributor Dogwoof

dogwoof.com/lifeanimated

► Trailer

Little wonder, then, that it’s been boom time of late for stories about the life experiences, coping strategies and achievements of autistic people. For an audience that has grown up lay-diagnosing autistic tendencies here, there and everywhere, these become not just feel-good tales of limitations being overcome, but highly relatable metaphors for the ways in which we all battle such challenges as sensory overstimulation and contradictory emotional signals.

In Life, Animated, the strategy in question – 23-year-old Owen Suskind’s deployment of Disney films, their dialogue and their characters as a language with which to converse with the world – is a particularly vivid and endearing one, which offers its own engagingly straightforward metaphor for how we use art. But Owen as a sort of embodiment of fandom – a walking object lesson in the consoling and guiding power of art – is only part of the story here. More interesting, perhaps, is Roger Ross Williams’s sensitive treatment of the family around Owen: articulate, loving high-achievers all, whose grief for the person they expected Owen to be gives way to a fierce determination to do right by the person that he is, and whose initial “rescue mission to get inside this prison of autism and pull him out” – as father Ron Suskind describes it – is adjusted along the way.

And that way is by no means easy. If Owen’s special means of communication helps to deliver him from loneliness by giving him a blueprint for social interaction and a subject for conversation, it’s not a solution to the challenges with which everyday life will continue to present him. Hollywood might have provided him with a lingua franca with the neuro-typical, but there’s no suggestion of a Hollywood-style “cure”.

It’s slightly odd, in fact, that since its prizewinning Sundance premiere this film has been so widely characterised as sunny and feelgood, because Owen’s trajectory is by no means one of uninterrupted progress – and his Disneyfied worldview is shown to have considerable limitations in terms of the tools it provides him with. Owen, his parents explain, responds to the “exaggerated expressions and emotions” of Disney characters, which are easier for him to read than subtler everyday cues. We duly see him live out his emotional life in vivid extremes: his romance with girlfriend Emily is all hearts, flowers and baby voices, until she breaks up with him, eliciting apocalyptic despair: “Why is life so full of unfair pain and tragedy? Why did this have to happen and make my life sad for ever…?” Of being bullied, Owen says, “At that point I fell into darkness and walked the halls of fear.”

But as Owen’s therapist says, “The real world is not a Disney script.” Owen’s primary-coloured melodrama is cute on screen, but it won’t necessarily help in achieving the independence and autonomy that his family craves for him. The film plays both sides somewhat, allowing such doubts to surface while still resorting to stirring Disney clips of loveable characters overcoming adversity with guts and faith to illustrate Owen’s quest through life. This slight doublethink arguably tells us something about documentary culture, and the pressure experienced by filmmakers to force real stories into conventional narrative trajectories: filmmakers and audiences alike are prone, like Owen, to applying unrealistic expectations to life in terms of narrative coherence, just deserts and triumph over adversity.

This does mean that some details which might have deepened the story have been backgrounded in favour of animation sequences – both Disney clips, and new work by French company Mac Guff – that emphasise the storybook elements of the narrative. Ideas around how Owen operates in the world and what we might be able to learn from it remain underdeveloped; although he attends and speaks at a conference in France concerned with looking at how autistic people’s obsessions help them to cope with life, we see little of what is discussed there.

Finally, amid the lionisation of Disney-as-saviour and the mild doubts presented over its drawbacks as a guide to life, something else stands out. We’re never told how Owen responds to films, animated or otherwise, that are made beyond his favourite studio (which licensed the clips, but had no editorial input into the film).

-

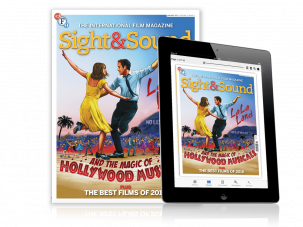

Sight & Sound: the January 2017 issue

Damien Chazelle’s modern musical La La Land, and a new look at exemplary toe-tapper Gene Kelly. Plus Krzysztof Kieslowski, Issa Rae, Eugène...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.