from our April 2013 issue

After three discursive but basically story-driven features, which have made him one of the most admired/hated figures in contemporary cinema, Carlos Reygadas lets it all hang out in a fourth feature which has very little narrative at all.

| Mexico/France/Germany/The Netherlands 2012 Certificate 18 114m 43s Crew Cast Dolby Digital Distributor Independent Cinema Office |

Post Tenebras Lux – the Latin title means ‘The Light After Darkness’ – takes its cues from Tarkovsky’s Mirror (1975). Framed in the now little-used Academy ratio, it stitches together fragments of personal memory and fantasy, garnished with a smattering of visual effects and the odd hint of social commentary, to build a poetic, psychedelic rhapsody in which the director’s tendencies towards abstract expressionism are allowed off the leash. Obviously Mirror’s patchwork didn’t include anything as disruptive or apparently anomalous as two glimpses of an English school rugby match or a visit to a European free-sex sauna, but then Tarkovsky’s life didn’t encompass stints at a private school in Yorkshire or working as a lawyer for the EU in Brussels, both of which do feature in Reygadas’s bio.

The film centres on Juan, the patriarch of a nuclear family, who is if not a stand-in for Reygadas then at least a channel for the author’s confessions, obsessions and fears. The prosperous Juan has brought his wife and their two kids (played most of the time by Reygadas’s actual son and daughter) to a new home he has built in the remote countryside. Aside from inevitable moments of awkwardness in their dealings with the locals, the family initially seems happy and contented. But the two opening sequences have already intimated trouble ahead.

The first is a suite of Steadicam shots of the little girl Rut padding about a waterlogged meadow as dusk falls and a thunderstorm breaks, surrounded by animals, all of them much bigger than she is; we later learn that this was her dream but the images of a small child apparently at risk cast an ominous pall over all that follows.

The second shows Juan’s household at night visited by a glowing red demon, a human-goat hybrid sporting both prominent human genitals and a long, arrow-tipped tail, which carries a toolbox and is observed only by the boy Eleazar. This is presumably the boy’s dream, matching his little sister’s and expressing his fear of his father – a fear that seems well-founded, given that Juan is soon seen going berserk as he ‘punishes’ one of his dogs and then admitting that he’s addicted to internet porn. The orgy sequence in the sauna (Juan watches while his wife is brought to orgasm by a stranger in the Duchamp Room – a bride ravished by her bachelors indeed) finds its objective correlative in a family row at the kitchen sink: Juan comes on raunchy to his wife but then lapses into a litany of complaints about her frigidity. In short, Juan has gone a bit wrong in the head.

Eventually, on his deathbed, moved by his wife singing Neil Young’s ‘It’s a Dream’ at the piano, Juan regrets his latter-day ‘sickness’ and loses himself in memories of ecstatic childhood experiences. The film, though, is mostly locked in the purgatory of the present: a world in which nature is both magical and threatening, a laidback rural community of elderly dope-smokers which turns out to be ravaged by alcoholism, crime, petty spite and ultimately murder and suicide, and a psychically skewed territory in which families are betrayed by absent or crazy patriarchs.

Reygadas envisions this purgatory magnificently, trumping his own more laborious efforts in Japón (2002) and Silent Light (2007) and leaving memories of the misbegotten Battle in Heaven (2005) far behind. To match the sheer sensory impact of the ambiguous tone and imagery in Post Tenebras Lux you’d have to look back to its distant ancestor, a film Reygadas has surely never heard of: David Larcher’s psychedelic odyssey Mare’s Tail, a forgotten classic of British indie cinema, similarly rooted in autobiography and equally haunted by the twin impulses to experiment and transgress. Like Larcher, Reygadas has grown impatient with rationality, with narrative and with psychological explications… but not to the degree that he loses sight of the pleasures and pains of banal realities such as Christmas family reunions or excursions to the seaside.

The most disruptive element here is the rugby match, dropped into the film in the middle and at the end. The two rugby scenes are wild anomalies – visually, linguistically, you name it – but their incursion into this Mexican backwater gives the film a kick when it threatens to become somnolent. They loudly champion a strategy that’s missing from this fallen Eden: teamwork.

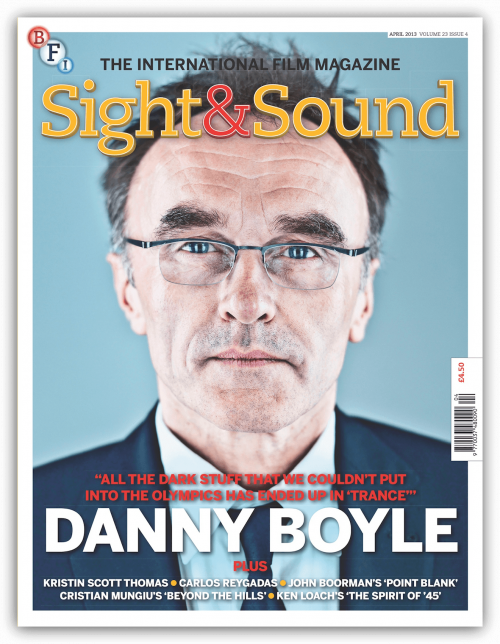

And in the April 2013 issue of Sight & Sound

The devil in the detail

In one of the most notable controversies of last year’s Cannes Film Festival, Carlos Reygadas drew fire for the perceived incoherence of his – dazzling or baffling – new film. But he’s not one to take criticism lightly, finds Fernanda Solórzano.

For and against: Carlos Reygadas

Is the Mexican director a master of experimental cinema or a self-indulgent provocateur with a condescending attitude to anyone outside his social class? Jonathan Romney and Quintín argue the toss.