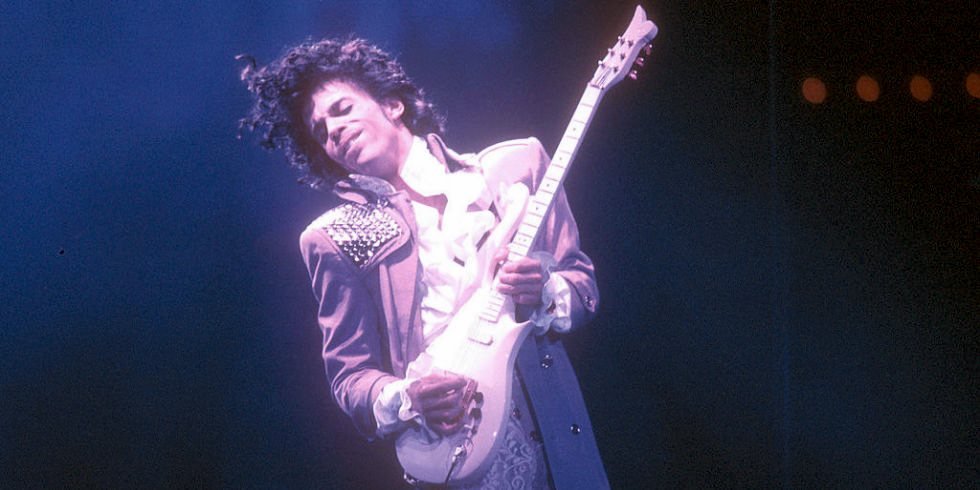

The star and animating force of Purple Rain, 24-year-old ‘Prince’ Rogers Nelson, must be the ultimate home-townboy-made-good. Half-black and half-Italian, the musician-composer hails from Minneapolis – a town whose musical associations were formerly limited to folksingers like Bob Dylan and Leo Kottke. Insisting on doing things his way, Prince has proceeded with a kind of stubborn amateurism which has paid huge financial dividends and yielded some interesting multi-media results.

He first burst into prominence in 1979 with the hit I Wanna Be Your Lover, but the X-rated lyrics of his subsequent album (Dirty Mind) were unacceptable to both black and white radio. Undeterred by the lack of air play, Prince toured and slowly increased his exposure through a series of LPs: Controversy, 1999 and Purple Rain (which in effect is a pre-released soundtrack to the film). Along the way, he discovered another band of Minneapolis funksters, The Time, who opened with Prince on an ’81/82 tour, by which time they had added a trio of lingerie-clad girl singers to the act: Vanity 6.

All these strands of personal and group history are melded in Purple Rain, which was shot in Minneapolis and allowed (with a few changes, including female lead Apollonia Kotero and the relabelling of Vanity 6 as Apollonia 6) most of Prince’s friends to play under their real names. It is interesting that, given all this ‘reality’, Purple Rain should end up delivering exactly what Walter Hill failed to in Streets of Fire: a “rock & roll fable” (as that film was announced in its opening titles).

Unlike Streets, Purple Rain operates purely and patently within the limits of pop’s romantic concerns. Certain elements recur often enough to acquire a clear resonance: the relationships between black and white, even down to the fact that the 1st Avenue club’s audience is all mixed couples; the ‘band of gold’ in the form of an earring that is passed back and forth between the Kid and Apollonia (even though the perpetual conflict in which men and women are depicted – the only unity being carnal and fleeting – is as much a rock convention).

Suggestions of homosexuality – a persistent rumour surrounding Prince – also abound. The Kid feels for his mother, yet is impotent to defend her against his father; rival Morris Day conducts a jive Abbott and Costello routine with his sidekick Jerome (who at one point disposes of an importunate woman into a dustbin for Day). Though the Kid’s ‘parents’ are portrayed by actors (Clarence Williams III being familiar to American audiences from TV’s Mod Squad), the story is definitely meant to be read as autobiographical (a tearful Kid dedicates Purple Rain to his father, ‘Francis L.’, presumably after John L. Nelson, Prince’s real, vanished, father).

The Kid’s musical progress is also self-referential: Darling Nikki, the song with which he insults Apollonia from the stage, almost parodies Prince’s early tactics of sexual outrage; Purple Rain is an effective statement about his ‘new direction’ in music – a claim to inherit, among other things, the mantle of crossover hero Jimi Hendrix.

As a debut and a savvy statement of personal enterprise, Purple Rain is quite an accomplishment. As a film, moreover, it is precisely the sort of vehicle one would have wished for Elvis in his Hollywood heyday: one which allows inept dialogue to be balanced by consistent visual style and successful cinematic flow. (Prince has lifted imagery from everywhere, from the Mod world to Hendrix glamour – yet his visual universe coheres better than that of, say, Flashdance or Streets of Fire.)

Unlike most ‘music films’, and more like successful film musicals of old, Purple Rain also shifts easily between ‘drama’ and musical performance – albeit with some help from the Kid’s omnipresent scooter. Other innovations make it notable as a youth-pic: the careful balance of sex and race in every scene; the representation of an environment where drugs are non-existent and alcohol pointedly a harbinger of evil; the Horatio Alger positivism which underpins the whole plotline. Considered critically, though, all the film’s best features are encapsulated in the montage which accompanies the When Doves Cry number – which also happens to be the video trailer that has been used to get those record crowds into the cinema.

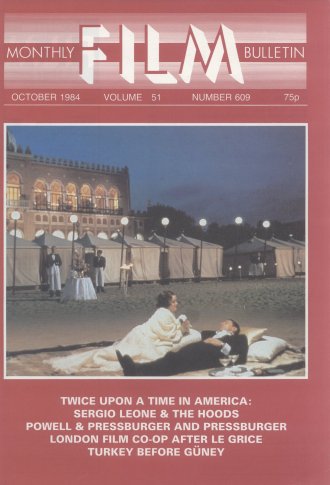

The complete Sight & Sound and Monthly Film Bulletin archive

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.