Web exclusive

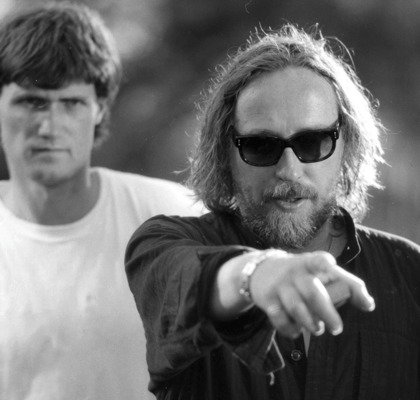

Credit: Ronald Grant Archive

Among the most important post-war German filmmakers, Werner Schroeter remained during his life a conspicuously little-seen and rarely discussed figure in the US and Britain, despite amassing a body of over 40 films, directing some 60 theatre and opera productions, garnering innumerable awards and earning the esteem of many of Europe’s foremost directors and actors. Resolutely uncategorisable, Schroeter’s work nonetheless acquired, as Fassbinder himself lamented, “that very convenient underground label, which in a twinkling made them admittedly beautiful but exotic plants, flowering so far away that one basically couldn’t deal with them”.

Born into a middle-class family in Georgenthal, Germany at the close of World War II, Schroeter studied psychology for three terms at the University of Mannheim before dropping out, then attended the Munich Film School, which he left after three weeks, having decided by the age of 19 that “it would be best to give myself to everyone” – and so taking up prostitution. It was during his period on the streets of Mannheim that Schroeter made the acquaintance of Erika Kluge, who under the stage name Magdalena Montezuma would become the principal among his many muses. It was a visit to the Knokke-le-Zoute Experimental Film Festival in 1967, where he discovered the so-called New American Cinema – and in particular Gregory J. Markopoulos’s Twice a Man – that brought home to Schroeter the possibility of a more personal, poetic and affordable film practice.

Working initially in 8mm, Schroeter made his breakthrough with his first feature Eika Katappa (1969), a boldly stylised pastiche of vignettes based largely on classical opera that managed to be simultaneously reverent and irreverent. In its otherworldly marriage of the ludicrous and the sublime, kitsch and heartfelt pathos, Eika Katappa already makes manifest what critic Hans Jensen identified as Schroeter’s “cardinal theme: the emotional yearning for self-realisation”.

Supported by German television through much of the 1970s, Schroeter furthered this theme with a rapid succession of works leading up to his first acknowledged masterpiece, Der Tod der Maria Malibran (The Death of Maria Malibran, 1971), which starred Montezuma in the title role as the legendary 19th-century mezzo-soprano who died at the age of 28, having purportedly “sung herself to death”. Inspired as much by the director’s lifelong passion for Maria Callas as by any details of Malibran’s biography (which are largely invisible in the film), the film asserted the place of emotion and sensuality within a cultural and social landscape still benumbed by recent brutalities and chastened against all romanticism.

As Schroeter said, “In my films I want to live out the very few basic human moments of expressivity to the point of musical and gestural excess – those completely authentic feelings: life, love, joy, hatred, jealousy and the fear of death – without psychologising them.” And so he did through a profusion of films both narrative and non-narrative, escaping Germany to work more frequently in Italy, Portugal and France, as well as Mexico, the Philippines, Lebanon, the US and Argentina.

Between Maria Malibran and his final, stark journey to the end of the night Nuit de chien (This Night, 2008), any list of Schroeter’s major achievements would have to include: his neo-neorealist saga Neapolitanische Geschwister (The Kingdom of Naples, 1979); his rending last film poem with Montezuma, Der Rosenkönig (The Rose King, 1986); his exploration of the Nancy Experimental Theatre Festival, Die Generalprobe (Dress Rehearsal, 1980); and his late masterworks Malina (1991) and Deux (2002), both of which boasted tour-de-force performances from Isabelle Huppert.

Commenting in a 2004 interview on his initial reaction to Fassbinder’s film In a Year of 13 Moons, Schroeter recalled: “I watched the film and said, ‘We are lucky, we saw something beautiful…’ That must really be the perfect epitaph.” For those with an openness to Schroeter’s singular visions, the sentiment seems just as fitting: “We are lucky, we saw something beautiful.”