Web exclusive

Men in Black

When Lowell Thomas first appeared on screen announcing to the world “Ladies and gentlemen – This is Cinerama!” at New York’s Broadway theatre on 30 September some 60 years ago, the face of cinema changed forever. Audiences gasped as the curtains flanking the narrator parted to reveal a vast, curved, louvred screen filling even the periphery of the visual field as, seated at the front of a roller coaster hurtling downwards into a Technicolor oblivion, they were pitched headlong into a bold new all-immersive world.

Since then, the film industry has seen a host of new technologies aimed at beefing up the sensory aspects of the cinema-going experience. Among the most salient have been the standardisation of colour, the wholesale expansion of the soundtrack into stereo and multi-speaker surround sound and the increased size and dimensions of the screen brought about by a plethora of widescreen formats that have included CinemaScope, VistaVision and Panavision.

Cinerama dramatically underscored the limitations of the 17-inch monochrome, monaural television screen, and pointed to new ways of how the exhibition sector could retain its share of the market. However, even at the premiere of This is Cinerama, the expense and inefficiency of the cumbersome three-projector system was already clearly apparent, with the visible joins between the projected images leading Mike Todd Sr, one of its original backers, to leave the company to pioneer the first commercially successful 70mm process, with its main design specification from the non-technically-minded financier that “everything comes out of one hole”.

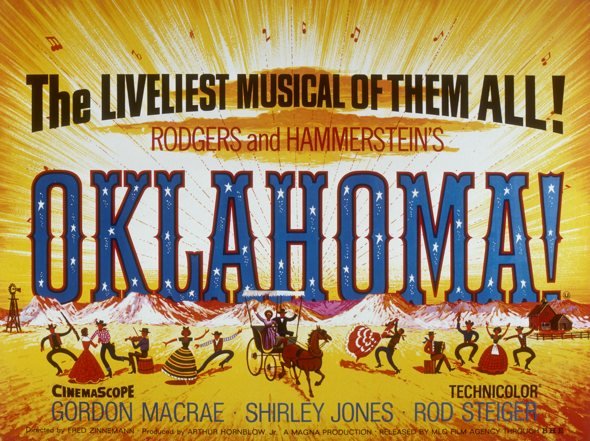

Todd-AO, first used for the adaptation of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Oklahoma!, which opened in 1955, led to a vogue for wide-gauge 70mm formats, with their increased size, clarity and depth of the projected image. While never intended to replace conventional theatrical exhibition, the ‘roadshow’ presentations of such formats and other later systems compatible with its projection equipment, such as Super Technirama 70 and Super Panavision 70, elevated the status of film screenings to ‘events’, in which the context of the presentation was as critical as the content. The bigger and more luxurious the venue and the greater the pomp and ceremony surrounding the actual screening, the more cinema distinguished itself against the upstart medium of television, until various economic forces resulted in cinema’s devolution back to the small-screen exhibition sphere of the multiplex and home theatre.

Smells, gimmicks, tricks and shocks

Less convincing attempts at wooing audiences back from their living rooms included Smell-O-Vision – used just once for a 1960 film, Scent of Mystery, produced by the Todd-AO founder’s son Mike Todd, Jr. – and William Castle’s infamous one-off add-ons like ‘Emergo’, a luminous skeleton on a wire that floated across the audience at the climax of House on Haunted Hill (1959), or ‘Percepto’, an electric buzzer placed in certain seats in the auditorium through which the worm-like creature at the heart of The Tingler (1959) was able to manifest its presence beyond the screen.

One might also include the initial 3D boom among such gimmicks, with Arch Oboler’s Bwana Devil released mere months after This is Cinerama, using a process called Natural Vision – perhaps somewhat misleadingly, as there was little ‘natural’ about viewing the image through green and red pieces of Perspex, especially when the twin projector system used to screen the film went out of sync, as it frequently did.

The widespread take-up of new exhibition technologies hinges not only on the seamlessness with which they are able to assimilate the viewer into their onscreen worlds, but their cost and ease of implementation. The recent third coming of 3D can be attributable to the switchover to digital projection. Much as critics and a large sector of the cinema-going public might hate to admit it, it has now been thoroughly assimilated into the theatrical landscape, with more titles released in 3D since Avatar just over two years ago than at any other point in history. 3D releases are still more popular than their alternate flat versions, while the recent reissue of Titanic 3D, scoring a top opening gross of all time in China of $67m, suggests that, whether one likes it or not, 3D is definitely here to stay.

What’s next?

4DX™ is currently being touted as the next big thing to hit the theatrical sector. One might see it as the logical synergy of all the aforementioned developments. To the added dimension of depth, it bolts on several embellishments that have a more palpable physical impact on the viewer: mechanised seats that roll, pitch and yaw in tandem with the camera’s movements; vibrating or pounding each individual audience member aggressively in the back during fight scenes like a renegade massage chair; jets of air or water directed at the head and back of the neck, to simulate anything from various weather conditions to aerial motion and bullets whistling past the head; strobe lighting in the auditorium during explosions or storm sequences; cascades of bubbles, billows of smoke and even diffusions of aromatic vapours to accompany the traditional image and soundtrack to the film in question.

The technology is the creation of South Korea’s CJ CGV, Asia’s largest multiplex chain, established as CJ Golden Village in 1996 through a merger between Korea’s CJ Corporation, Hong Kong’s Golden Harvest and Australia’s Village Roadshow, although the latter two interests dropped their stake several years ago. CGV owns almost 700 screens in South Korea alone, including what is currently the largest screen on the continent, the Starium in Incheon. It also operates several venues equipped for IMAX and IMAX 3D presentation, and the renowned Ciné de Chef, a luxury theatre-cum-gourmet restaurant that opened in May 2007, seating a maximum of only 30 visitors paying the equivalent of up to £50 a pop. In recent years it has expanded its operations further throughout Southeast Asia, with additional venues in China and Vietnam, and even one in Los Angeles.

But it is with 4DX, developed by its subsidiary CJ 4DPlex, that the company looks most set to leave its mark on the map. The system celebrated its commercial debut in Seoul in January 2009 with Avatar’s South Korean release. According to the company website, there are currently 29 installations dotted around the world, ten of which are in Korea, with new venues opening on a monthly basis. Others have been unveiled in China and Thailand, and in Mexico, where 11 sites are listed. The expansion plans are ambitious, with 50 venues touted by the end of this year, including ones in Poland and Israel, and a breathtaking 1,500 installations planned by 2016.

Putting you in the picture?

Of course, we’ve been in a similar position before. Even the lingo remains remarkably similar, with the system’s tag-line “Don’t just watch the movie; be in it” echoing those of yesteryear, that “Cinerama will put YOU in the picture!” or “You’re in the show with Todd-AO.” Perhaps the crucial difference with this recent attempt to osmose the viewer completely into the viewing experience, on which 4DX will either stand or fall, is that the films screened using the process are not custom-made for it. The most significant drawbacks to both Cinerama and Todd-AO was their usage of non-standard projection equipment, film gauges and frame rates, which severely limited screening opportunities for those films made specifically to showcase the systems (although Todd-AO titles like Oklahoma! were filmed in alternate 35mm versions, and later productions reverted back from 30fps to the 24fps standard so they could be released more widely in optically-reduced standard-gauge prints).

In a 4DX presentation, the film is fundamentally the same as one can see in any other venue, albeit accompanied by chair motions and the other environmental additions created by the CJ 4DPLEX programmers. All the titles so far to have received the extra-sensory makeover, which include Star Wars, The Hunger Games and Puss in Boots, have been Hollywood, not Korean, productions.

Given this, experiencing a recent performance of Avengers Assemble in the dedicated auditorium of Seoul’s Yongsam CGV multiplex raised a number of questions. In what ways do these adjuncts influence our reception of the film’s diegetic world? For example, in your classic Hollywood model, the good guy and the bad guy might be distinguished by different framing, lighting or accompanying music. Here in the fight scenes, it was more difficult to know who to root for. Whether Thor hits Loki or Loki hits Thor, the viewer still gets a jarring jab in the small of their back from their chair.

Are films such as The Avengers even particularly well-suited to the technology? As many have observed, the rapid-fire editing of contemporary Hollywood action movies is already ill-suited to stereoscopic viewing, as it so relentlessly carves up space and time that it leaves little possibility for the spectator’s full immersion.

Avengers Assemble

In a similar vein with 4DX, the transitions from the exterior aerial scenes – in which the viewer is wafted by a cooling breeze – to the relatively static interiors, felt pretty jarring at times, while during some of the longer dialogue scenes the automated seat seemed unsure of what it should be doing, leaving the viewer relatively distanced from what was going on save for the occasional twitch or throb of the chair to remind you it was still there. Would a more measured film like Titanic have been better suited?

Or maybe, if the technology does catch on, a new generation of titles made specifically for it will emerge that are more aesthetically rewarding, just as films originally shot in 3D and mindful of its potential are generally more satisfactory than those shot flat and post-converted. If nothing else, perhaps the more physical additions serve to underscore how invisible developments in CGI special effects, 3D and digital projection have become in recent years.

Teaming up with the studios

Given the transformative effect of the technology, it also seems pertinent to ask who actually designs, or ‘scores’, the kinaesthetic / sensory / olfactory track that accompanies the main cinematic text? Is this done in conjunction with the original studio that produced it?

This was apparently the case with the recent Titanic re-release, with the South Korean company partnering with Twentieth Century Fox and LightStorm Entertainment to perfect the 4DX post-production. CJ 4DPlex is scheduled to open its first programming lab in Los Angeles at the end of August, and apparently several Hollywood studios have shown a keen interest in expanding into the next dimension. But it is certain that many of the productions to have received such treatment thus far were not produced with such arrangements in mind.

Along with its south-east Asian genesis, all of this underscores one of the more remarkable aspects of 4DX – the fact that there are currently no venues in the developed exhibition markets of North America or Europe. Even Japan has come fairly late to the game, with the Kadokawa Cinema Shinjuku tipping its toe tentatively into the icy water on 7 June with Sadako 4D, an attempt to up-sell the scares of the recent Sadako 3D reboot of the Ringu franchise.

This is a complete reversal of the expansion pattern of previous North American-developed, non-standard formats such as Cinerama and IMAX, their venues purpose-built as tourist attractions and national status symbols, spreading across the economically advanced cultural capitals of the Western or Westernised world.

The first permanent Cinerama theatres outside of the US were in London, Montreal, Tokyo and Osaka, while until the mid-1990s, there were more IMAX sites in Japan than any other country outside of America. This astonishing rise of 4DX in the East – due to the CVG’s close partnering with exhibition chains such as Thailand’s Major Cineplex and Cinemacity, which operates in Central and Eastern Europe and Israel, as well as Latin America’s mighty Cinepolis chain – might well be better attributed to national cinema-going habits rather than a seismic shift in economic power, but it is intriguing nonetheless.

Cynics might well denigrate 4DX’s transformation of the viewing experience from a metaphorical roller coaster to a more or less actual one as a one-off novelty, and hardly worth paying inflated ticket premiums on a regular basis (admission at the Yongsam CGV cost 18000 won – about £10 – in a country where the average ticket price is 8000 won, or less than half of this).

But at a time when digital projection will effectively mean that the theatrical experience is not much different to watching a film at home, save for the bigger screen and bigger audience, for the exhibition cinema to thrive in the 21st century, it is going to need the same sort of bells and whistles that Cinerama provided back in 1951. And isn’t there a part within all of us who would like to feel like Titanic’s Leo just for one moment, kings of the world, hair billowing in the wind before that sinking feeling when we become aware that it might be coming to an end?