Web exclusive

Raoul Walsh’s The Big Trail

With its rich array of retrospectives, rarities and restorations, the Cinema Ritrovato festival hosted by the Cineteca di Bologna has become an annual must for cinematheque programmers, distributors of classic movies, film historians, archivists and curators. This year’s 26th edition proved characteristically rewarding, despite the absence of its artistic director – the estimable Peter von Bagh, also head of Finland’s Midnight Sun Film Festival – due to poor health. A great pity, not least because his skills as a public speaker were missed; as usual, many of this year’s screenings were introduced, but few of them well, and some with plot-spoilers.

Nevertheless, notwithstanding some atypically clumsy projection, the film programme itself did deliver. A timely survey of early 30s films about the fallout of the Wall Street Crash unearthed welcome rarities by the likes of Max Ophuls, Frank Borzage, Mervyn LeRoy and Paul Fejös, though none boasted the directors on top form. (Sadly I missed Julien Duvivier’s David Golder, which was reportedly a real find.)

A selection of some of the lesser known films by Raoul Walsh offered a reminder of what a fine if uneven director he was, often at his best with spectacular scenes of vigorous mass activity. While a silent adaptation of Ibsen’s Pillars of Society (1916), for example, demonstrates no discernible promise of things to come, the remarkable The Big Trail (1930), shot in Fox’s 70mm Grandeur process, sees Walsh revelling in the opportunities afforded by the wide screen both to evoke the epic scale of his characters’ westward odyssey and to include in his vast but meticulous compositions more intimate aspects of the pioneering experience: women painstakingly brushing their long tresses before their journey starts; the same women after an Indian attack, sobbing inconsolably over stony graves marked with wooden crosses and broken wagon wheels.

Though Raffaello Matarazzo’s La nave delle donne maledette (The Ship of the Cursed Women, 1954) came highly recommended, it would be absurd to overpraise such an incoherent costume drama; still, its steady descent into cleavage-fixated sensationalism – as it went off the rails, my reference points slid from Rohmer and Ruiz, via Freda, Fellini, Meyer and the mondo and Carry On films, to the John Farrow of His Kind of Woman – is certainly divertingly lurid.

Jean Grémillon’s Remorques

The real highlight, for me and many others, was the retrospective devoted to Jean Grémillon. Two silent features – the realist Maldone (1927), and the experimental, almost minimalist foray into near-expressionism Gardiens de Phare (1929), the latter accompanied quite brilliantly by pianist Maud Nelissen – were remarkable for Georges Périnal’s camerawork, the subtle naturalism of the acting, and Grémillon’s keen feeling for places and the faces of the people who inhabit them.

And if the talkies I caught – Gueule d’amour (1937), L’Étrange Monsieur Victor (1938) and Remorques (1941) – felt a little more conventional, they were no less impressive. The second features a marvellous performance by Raimu as a much-loved Toulon shopkeeper with a dark secret; the others find Gabin on peak form, first as a womaniser undone by his love for a girl harder to pin down than himself, then as a lifeboat captain coming to doubt his job and his marriage. The writers here are Charles Spaak and Jacques Prévert, but again it’s the director’s attention to performance and visual details and his readiness to confront difficult emotional dilemmas head-on that make the films so persuasive and powerful.

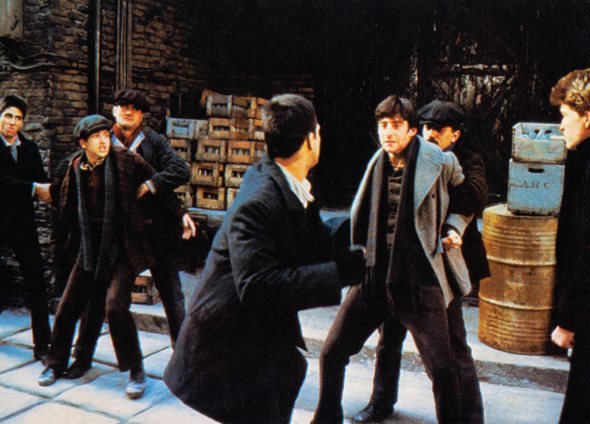

Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America

And then there was Cineteca Bologna’s own restoration of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America (1983), complete with six hitherto unseen scenes cut for the film’s release. Though the visual quality of this footage (lasting around 26 minutes in toto) is inferior to the rest of the film, it undoubtedly constitutes a major discovery; we can now see, for example, how and when Noodles (Robert De Niro) met Eve (Darianne Fluegel), while a scene in which Secretary Bailey (James Woods) meets with Jimmy O’Donnell (Treat Williams) helps to clarify the crucial final conversation that follows.

Likewise, a new scene involving the teenage gang swimming and another in which Deborah (Elizabeth McGovern) plays Shakespeare’s Cleopatra fill out metaphors a little vague in the release version, while a brief but fascinating dialogue between Noodles and his chauffeur (Arnon Milchan) brings a fresh slant to the specifically Jewish aspects of the story. Dramatically, the film is as mesmerising as ever; the restoration confirms it as Leone’s most audaciously ambitious and satisfying achievement.