Geography and landscape are important, and here we are at something of a disadvantage; the UK has a rich diversity of locations but doesn’t feel like a place where you can easily get lost. Where the politicians of the United States have become adept at inspiring notions of freedom and opportunity across a substantial unified landmass, for hundreds of years Britain’s geographical self-conception was contingent on the ways in which territory was inscribed in the rhetoric of empire. Colonies, protectorates and mandates were not considered separate countries or regions but imagined as constituent parts of a bigger whole.

With the collapse of empire in the mid-1900s this (distorted) sense of expanse dissipated, a moment that coincided with the end of British cinema’s ‘golden age’ after World War II and gave way to an era of realist introspection. Indeed, if the 20th century belonged to the US, then it was concurrent with a geopolitical shrinkage we are still struggling to come to terms with on these shores. Perhaps it is this lingering deflation, coupled with a still-ossified class structure, that has closed down on the possibility of imagining an ‘out there’ that exists off frame. Put simply, we got smaller and so did the pictures. A private and weather-bound island people, we have been forced to make a virtue of the interior and have become expert explorers – both in film and television – of the domestic. Consequently, delivering at scale requires a retreat into the familiar generic bosom of wartime epic and period drama. In 2017 Christopher Nolan gave us Dunkirk; Joe Wright has just served up Darkest Hour; Ridley Scott is developing Battle of Britain; and David Mackenzie will take us even further back in time this year with his Robert the Bruce project Outlaw King.

The cast of American Honey (2016)

This isn’t to say that the contemporary mood cannot be mapped productively against the period feature. Indeed, revisionism within the genre – Belle (2013), Lady Macbeth (2016) or the forthcoming Colette, starring Keira Knightley – can feel as fresh or urgent as anything delivered in the present tense; Mike Leigh, as English a filmmaker as they come, is just one example of a director who navigates contemporary and period dramas with equal skill, while Amma Asante continues to offer up energising alternative perspectives within the heritage mould. Nevertheless, a predilection for, and preponderance of, films set in the past can skew the picture in terms of diversity and, more importantly here, robs us of more direct opportunities for state-of-the-nation engagement.

It may feel old-fashioned, unfashionably patriotic, even, to bemoan the lack of contemporary national specificity in our cinema. An increasingly globalised, transnational film business opens up productive channels across which aesthetic and cultural currents can flow, providing opportunities for directors to work internationally and influence local contexts. German émigrés changed the look of 1930s Hollywood; Alejandro González Iñárritu, Alfonso Cuarón and Guillermo del Toro continue to invigorate and innovate within mainstream US filmmaking; it is possible that ‘our’ filmmakers could yet have a lasting impact on the dynamics of the American independent scene. After all, American Honey and You Were Never Really Here both bring signature naturalist styles to bear on their cinematic landscapes, while 12 Years a Slave saw McQueen deploy his trademark visuals to wincing effect within a specifically American context, winning over audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. Conversely, it would be churlish to deny the off-beat charm of Yorgos Lanthimos’s anglophone The Lobster (2015) or the mounting excitement about Sebastián Lelio’s forthcoming English-language debut Disobedience, set in North London’s orthodox Jewish community.

Ken Loach and Dave Johns on location for I, Daniel Blake (2016)

Still, for so many acclaimed independent voices to be working outside the country at the precise moment when a national debate rages around who we are and what we believe in is troubling. What, for example, would 2016 have felt like without the release of I, Daniel Blake, Ken Loach’s excoriating attack on Con-Dem austerity politics? Almost 50 years after Poor Cow (1967), and with more than 20 feature films and countless TV dramas and documentaries under his belt, Loach won the Palme d’Or for a second time and achieved the biggest domestic box office for any of his films to date. For a filmmaker often better appreciated in Europe than on home turf this was critical-commercial-cultural alchemy.

Cannes boost aside, audiences came out because the film resonated so deeply with the here and now. That’s certainly what the team at distributor eOne was banking on and they positioned the film accordingly. Our elder statesmen of social realism won’t be making films forever, though, and who knows if the directors who gave us Fish Tank (2009), Dreams of a Life (2011), The World’s End (2011) and Starred Up (2013) will return to us with contemporary stories any time soon.

Ellie Kendrick and Hope Dickson Leach shooting The Levelling

We might look to television – that other persistent cause of hand-wringing for those who believe in the sanctity of the big-screen experience – for our salvation, but the dynamic is replicated there too: over the past five years our indie directors have been tied up stateside with Looking (2014-15), I Love Dick (2016-17), Transparent (2014-) and Mindhunter (2017), and Andrea Arnold is slated to direct the entire second series of the roundly fêted Big Little Lies this year.

All is far from lost, however. It would be utterly remiss not to mention the filmmakers who are yet to set sail for the land of free and of whom we should feel rightly proud. Our contemporary landscape would be a barren place indeed without Joanna Hogg’s forensic explorations of the upper-middle classes, Jonathan Glazer’s bold visions, Clio Barnard’s heart-wrenching dramas or Peter Strickland’s Europhile pastiches. Nipping at their heels is a talented bunch of filmmakers who have spun gold out of austerity in recent years, marking 2017 in particular as the year of the low-budget triumph. Moreover, and somewhat unexpectedly, it was a trio of sensitive and compelling farm-set dramas – Hope Dickson Leach’s The Levelling, Francis Lee’s God’s Own Country and Clio Barnard’s Dark River – that best allowed us to take the national temperature over the last 18 months.

Shola Amoo shooting A Moving Image (2016)

So, what happens next? Well, if the UK film industry can put its diversity money where its mouth is, we should see work coming through that’s as fresh and energetic as the debut features we’ve enjoyed in the last few years from Shola Amoo (A Moving Image, 2016), Babak Anvari (Under the Shadow, 2016), Rungano Nyoni (I Am Not a Witch, 2017) and Sarmad Masud (My Pure Land, 2017). Whisper it quietly, but a truly heterogeneous talent pool may even help to usurp the long reign of the British poetic realists, giving way to something altogether more distinctive and plural. With filmmakers exploring their heritage in Iran, Zambia and Pakistan, it may prove difficult to apply conventional definitions of ‘Britishness’ here too, but for much more exciting reasons. And if we can create the conditions for those voices to stay working in the UK, so much the better.

Much as we might wish it, we cannot keep our filmmakers chained to the national radiator. In the same way that musicians, novelists and academics take advantage of well-trodden circuits in the US, it is inevitable that filmmakers will follow suit. Nevertheless, if the pathways of progression for our directors require them to leave the country then we have some questions to answer. There hasn’t been a more interesting moment in the last 20 years to plumb the depths of the national psyche. Our filmmakers have to help us do that work: the health of the nation depends on it.

Read more in the May 2018 issue of Sight & Sound

Ride lonesome

A clear-eyed, unsentimental portrait of a young boy’s relationship with an ailing race horse and their epic trip across a broken America to find a stable home, Andrew Haigh’s Lean on Pete offers a modern spin on America’s founding myth. By Michael Leader.

Dangerous liaison

Michael Pearce’s tense Jersey-set debut feature, Beast, steers clear of psychosexual thriller cliché to present a complex character study of a young woman who falls for an enigmatic stranger while a serial killer is terrorising the island. By Nikki Baughan.

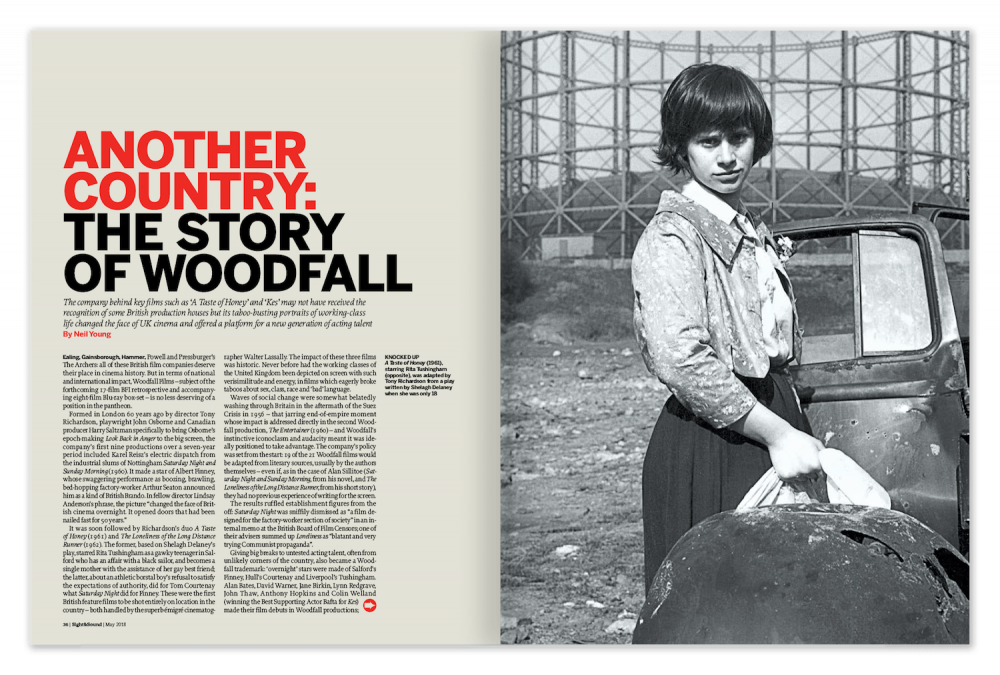

Another country: the story of Woodfall

The company behind key films such as A Taste of Honey and Kes may not have received the recognition of some British production houses but its taboo-busting portraits of working-class life changed the face of UK cinema and offered a platform for a new generation of acting talent. By Neil Young.

-

Sight & Sound: the May 2018 issue

120 BPM salutes the courageous Aids activists of the early 90s. Plus runaway British indie directors, Beast, Lean on Pete, Woodfall Films, Western...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.