Web exclusive

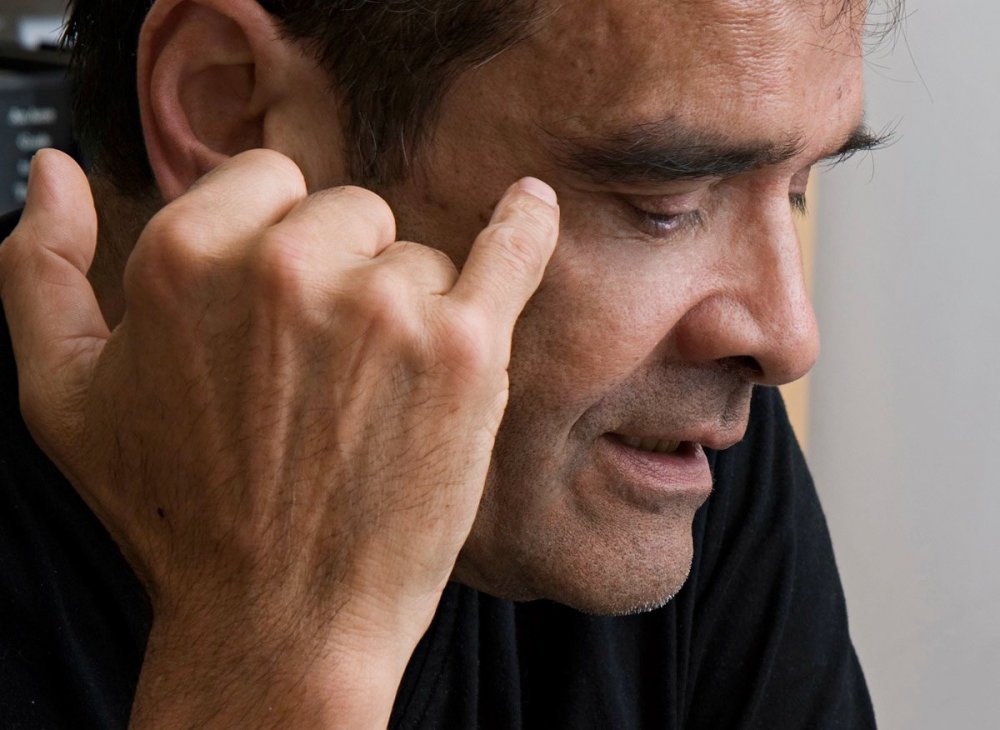

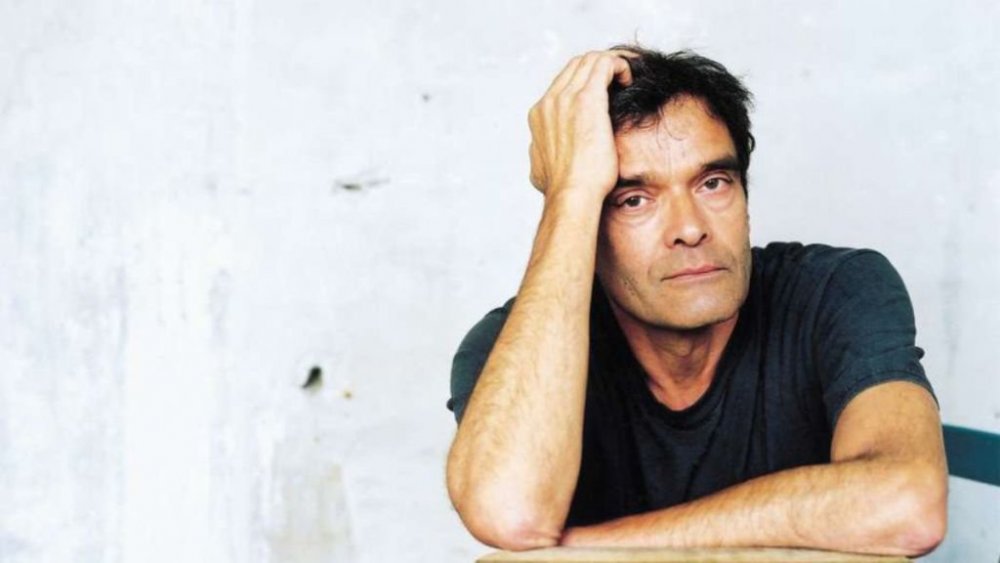

Harun Farocki

Dear Harun,

You may not remember this, but we met once during the Berlinale a couple of years ago to celebrate the premiere of your friend Christian Petzold’s film Barbara. The film was a big hit, everyone was in high spirits, and you were gracious enough to exchange a few words with me even though I was too nervous to say anything of consequence. What does one say when finding oneself face to face with one’s hero? There ought to be a manual for this.

Your celebrated 2011 show at MoMA, the first time I immersed myself deeply in your work, was titled ‘Images of War (at a Distance)’. Your work as a whole conveys the notion that a certain distance is necessary to understand things that profoundly affect our lives, like images, or war. And so, from a distance, I will offer this attempt to articulate why your work means as much as it does to me, which I failed at doing in your presence.

I remember that I even failed that evening to introduce myself to you. I used to proudly identify myself as a cinephile, but lately I qualify that by calling myself a recovering cinephile, or a disenchanted cinephile. What do I mean by this? A certain prominent film scholar who shall go nameless here (though it should be acknowledged that this scholar has written eloquently about your work) once made an astute observation that the greatest sex in the world would also be the most horrifying sex in the world. By definition, the greatest sex in the world is the kind that you wouldn’t want to stop. And like many things (especially things I’ve encountered in my time at art school), sex that never ends sounds much more appealing in concept than in practice.

I share this anecdote because it vividly describes the shifting of my relationship to cinema, from enthusiastic enjoyment to overwhelmed exhaustion, from being in love with every new film to feeling trapped in the same dull sensation, an endless flicker. Today you don’t even have to be a cinephile to experience this condition; everyday life is now a constant procession of screens. Images are as cheap and freely accessible as our water supply, and we take both for granted at our peril. As more parts of the world are issuing drought warnings and rationing water, we are increasingly submerged by images, practically drowning in them, always looking, looking. And with all this looking, what do we actually see?

The great artist Trevor Paglen has postulated that we are now in fact living in a “regime of images”; and so we must ask, how shall we conduct ourselves as its subjects? If images are the rulers of our existence, then we must assume they behave the same way as our other rulers: by hiding the facts as much as they pretend to share them with us. When we look at an image, can we not just look at it, but through it, around it, beyond it, to find out what is hidden? Things such as: where it comes from, how it came into being, the forces that determine its meaning and our response. And if we are able to see and do all these things, what then can this kind of seeing inspire us to do, lest we just spend a lifetime of just looking?

Harun Farocki

For all of this, I am grateful to you Harun, and your films that strive to attain and disseminate this kind of seeing. Your work is frequently categorised as ‘essay filmmaking’. Among the ranks of the great ‘essay’ filmmakers, your films may not be as formally audacious as Godard’s, or as seductively subjective as Chris Marker’s. But you mean the most to me because you are not just an ‘essay’ filmmaker, but a ‘sober’ filmmaker. You helped me sober up from the dead-end love known as cinephilia and discover a new way to love movies and images, one that can reach beyond them towards something more essential: the world itself.

I suspect that your ability to inspire this new way of relating to cinema is due to the ways your work functions besides ‘filmmaking’. Sometimes your work resembles scientific research, the way you dissect images and study their guts. Sometimes you are like an engineer who can see how images work within massive social systems. Sometimes you are an economist who assesses how images are assigned value, whether aesthetically or culturally. These left-brain descriptions might peg you as someone who’s more scientific than artistic, but quite the contrary, what is special about your work is how you are able to transform scientific methods and systemic looking into a kind of poetry.

And so I use the ‘p’ word, ‘poetry’ to exalt you, even as you’ve been disparaged with another ‘p’ word: pedagogical. Yes, you are a teacher – our mutual friend Volker Pantenburg has written about the recurring appearance of blackboards in your works – and one could say that you treat the entire frame as a chalkboard upon which you conduct your image studies. Watching your films, there’s no question that you want not just to show, but to teach us something. And you know what? That didacticism is refreshingly upfront and honest in a world where hiding behind the mystery and aura of seductive images is the chief strategy for attaining cool. I think the pedagogical aspect is one of the most brilliant facets of your work, because what you teach is that every image itself is its own teacher. Every image has its own subliminal instruction manual that tells us how we should look at it and feel about it.

So maybe what’s needed is a counter-instruction manual that helps us to decode those instructions, so that we might learn how not to follow them.

That way, maybe we might see something else than what the image wants us to see: a reality that’s deeper than images.

-

The Greatest Documentaries of All Time poll

What are the greatest documentaries ever made? We polled 340 critics, programmers and filmmakers in the search for authoritative answers.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.