Web exclusive

Floating Skyscrapers (Płynące wieżowce)

It would be fair and indeed accurate to say that, for all the undoubted creative excellence of Polish cinema in a great many fields, the country is not renowned for its contributions to LGBT filmmaking. Although the recent book-length English-language overview Polish Cinema Now! (edited by Mateusz Werner, 2010) includes a chapter on feminist and homosexual themes in post-1989 Polish cinema, it makes dispiriting reading, with its author Anita Piotrowska opening with some blunt scene-setting:

Although homosexuality stopped being a criminal offence in Poland in 1932, homosexuals were almost absent from the Polish People’s Republic-era cinema [ie the period up to 1989] because they “threatened the healthy fabric of the nation”. Even if they did make it onto the screen, it was merely as characters that were as irrelevant as they were shady and, consequently, either comically “bent” or mentally degenerate, shamelessly exploitative, or leading astray minors. In short, gays under Polish communism were in the same grey area as prostitutes or black market money-changers, which is exactly how they were portrayed in Polish cinema.

Although things did change as Poland became more westernised, crude caricatures were still far more common than nuanced characterisations well into the post-communist era, although Piotrowska singles out The Egoists (Mariusz Treliński, 2000), The Lovers of Marona (Izabella Cywińska, 2005), Drowsiness (Magdalena Piekorz, 2008) and the short Aria Diva (Agnieszka Smoczyńska, 2007) as honourable exceptions.

| In the Name Of is now on UK theatrical release. Floating Skyscrapers screens on 17 and 20 October in the London Film Festival and is released in the UK on 6 December. |

There were also a handful of documentaries, such as Homo.pl (Robert Gliński, 2007), Coming Out in Poland (Sławomir Grünberg, 2008) and Trans-Mission (Julie Land and Justyna Struzik, 2008), the latter being an even rarer example of a serious study of the physical and psychological ramifications of having a sex change. Piotrowska concluded that despite the comparative paucity of unabashedly LGBT Polish cinema between 1989 and 2010, there was sufficient evidence of progress in the new millennium’s first decade to end her chapter with an upbeat “Thankfully, the first signs of a breakthrough are already visible.”

While Polish LGBT cinema is still undoubtedly at the baby-steps stage, plenty of evidence has emerged in the last three years to support Piotrowska’s optimism. Newcomer Jakub Gierszal made a considerable splash in The Suicide Room (Jan Komasa, 2011) and Yuma (Piotr Mularuk, 2012) in which he played characters whose sexuality was decidedly fluid. The first film in particular was a substantial local hit, suggesting that younger audiences were far less fazed by LGBT material than their older compatriots. 2012 also saw the premiere of the independently-shot digital feature Secret (Przemysław Wojcieszek), which co-starred the openly gay Tomasz Tyndyk as a drag queen trying to rebuild a relationship with an estranged relative: as dark secrets go, the younger man’s is considerably less noteworthy than his grandfather’s 1940s anti-Semitic activities.

Alongside these, the first annual Polish LGBT Film Festival was staged at the Warsaw Cinematheque in July 2010. Come 2011, its screenings were also being held in Gdańsk, Katowice, Łódź and Poznań, and Wrocław was added to the 2013 roster, offering what in many cases were the first opportunities for Poles to catch both current and historical LGBT productions on domestic cinema screens.

In the Name Of

This year also saw two genuine domestic breakthroughs in the form of Małgorzata Szumowska’s In the Name Of and her former assistant Tomasz Wasilewski’s Floating Skyscrapers. Whereas most previous Polish films either skirted around the issue of gay desire or presented it as a comparatively minor subplot, in these films it’s the central theme, and In the Name Of also features the first instance of an established Polish star playing an unambiguously gay protagonist in a mainstream film that treats the topic of homosexuality both intelligently and sensitively. It premiered at the 2013 Berlin Film Festival to a generally warm reception, including a Teddy Award for the best feature film on an LGBT subject, and debuted at the top of the Polish box-office charts when it opened commercially this September.

Perhaps more surprisingly, despite some predictably knee-jerk condemnation of the film (often sight unseen) in the conservative media, Szumowska escaped the direct wrath of the Catholic Church, which has so far refrained from making any formal statement, although the film has reputedly become a must-see for individual priests. Indeed, some left-wing commenters felt that Szumowska should have been more directly critical of the Church: in a Q&A following a recent London screening, she confirmed that “it’s not an attack, and we did this on purpose. We were really conscious that we wanted to make a film that is not judgmental.”

Szumowska wrote the lead role specifically for Andrzej Chyra, an actor probably best known in Britain for supporting appearances in Andrzej Wajda’s Katyn (2007) and Szumowska’s own Elles (2011), but at home he can appear in anything up to half a dozen films per year (he was in three of the competition films at this year’s Gdynia Film Festival, where In the Name Of won Best Actor, Best Director and the Silver Lion runner-up Best Film prize).

In the Name Of

Chyra’s intense gaze, reminiscent of Terence Stamp’s, makes him equally compelling as a psychopath or a priest. As the latter, he’s wholly convincing as Father Adam, relocated to a small town in murky circumstances whose nature most will swiftly guess. Although Szumowska’s portrait of the Church is broadly sympathetic, she repeatedly highlights its tendency to sweep potentially controversial issues under the carpet instead of tackling them head on – something of which Adam proves just as guilty as his avuncular bishop (Olgierd Łukaszewicz).

On the face of it, Adam would appear to be an exemplary standard-bearer for the Church, running a community centre for boys from troubled backgrounds (all but one played by non-professionals, in a nod to Szumowska’s documentary roots), and for the most part communicating with them frankly and honestly in language that they can readily understand. He also rejects the advances of a frustrated housewife, and masturbates to relieve sexual tension, both of which initially suggest that he’s come to terms with the peculiar requirements of his calling.

It’s only when he becomes the protector of the much-abused Lukasz (Mateusz Kościukiewicz) that his desires start to interfere with the execution of his duties, and the only person he can unburden himself to is his faraway sister via Skype (in a hi-tech equivalent of the confessional). This is one of several scenes that nudge both melodrama and unsubtle symbolism: at other points, Adam drunkenly dances with a portrait of the Pope (Benedict XIV, not the still-ubiquitous-in-Poland John Paul II) and later runs through a cornfield with Lukasz, both men gibbering and chest-beating as though reverting to a primal state, a scene that will be either sweet or insufferable according to taste. But for the most part it’s a brave and agenda-setting film that may well be seen as a genuine milestone.

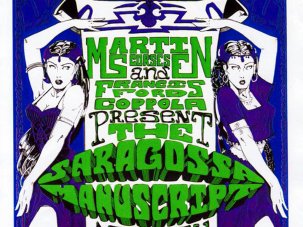

Floating Skyscrapers

While Floating Skyscrapers is ostensibly about the same subject (the temptations and challenges of negotiating socially and culturally ‘forbidden’ desires), the focus is substantially different. Its twentysomething protagonist Kuba (Mateusz Banasiak) is a swimmer with championship potential, if only he could focus on the matter at hand instead of being smitten by Michal (Bartosz Gelner), a regular at the local gym who turns up at a gallery opening to which Kuba is reluctantly dragged by his girlfriend Sylwia (Marta Nieradkiewicz).

Initially hesitant experimentation swiftly turns to full-blown obsession, accompanied by what must surely be the most graphic gay sex scenes yet seen in a Polish film – but their relationship is far less successful on the psychological level, thanks to Kuba’s hesitancy about breaking up with Sylwia and an evident reluctance to come out publicly in a society where queerbashings are all too rife. In this respect the film is far more pessimistic than Szumowska’s, although perhaps more bluntly realistic about present-day Polish realities.

Wasilewski first revealed a distinctive eye for space and architecture in his debut feature In a Bedroom (2012), whose bedhopping female protagonist was more interested in the spaces inhabited by her various lovers than the men themselves. Floating Skyscrapers can’t match its predecessor for conceptual originality (narratively, it offers little that John Schlesinger didn’t depict in Sunday Bloody Sunday over 40 years ago), but Wasilewski offers similarly unexpected repurposings of everyday settings like car parks, cityscapes and swimming pools, not to mention the equally fruitful landscape of the human body. During an energetic bout of cunnilingus, the focal plane seems to dart across Sylwia’s pubis with as much alacrity as Kuba’s tongue, while a pivotal argument between Kuba and his coach is conducted in the background of a synchronised swimming rehearsal. The film often goes into hypnotic little reveries that match Kuba’s and Michal’s detached mental states, whether swimming underwater or driving through multiple levels of a car park, and Jakub Kijowski’s ’Scope compositions are often intensely pleasurable in themselves.

Floating Skyscrapers

Since stills and clips could well create the impression that Floating Skyscrapers is a somewhat self-conscious art movie, it’s worth emphasising that it’s often very funny: at a Gdynia screening, a huge belly laugh accompanied the scene in which Michal suddenly comes out to his parents, who react (or rather don’t) by blanking the news completely and continuing to talk about domestic minutiae. Meanwhile Kuba’s mother sits at home teaching herself Japanese with the aid of such dubiously useful phrases as “Mr Tanaka divorced his wife last year and now has to pay alimony”, while a football commentator repeatedly berates a player named Wasilewski for being useless. But his namesake is rapidly becoming one of the more interesting younger Polish directors: if he hasn’t yet achieved a wholly convincing match of form and content, it won’t be at all surprising when he does.