feature | from our July 2012 issue

The Ball at the Anjo House (1947)

The Japanese director Shindo Kaneto celebrated his 100th birthday in April 2012, an occasion heralded by last year’s touring retrospective in the United States, and celebrated with tributes in his hometown of Hiroshima and a two-month retrospective at BFI Southbank in London. At work in the industry since the 1930s and a director since the 1950s, Shindo made his final film Postcard (Ichimai no hagaki) only two years ago, by which time he was among the last living links – and certainly the last active one – to the filmmaking generation of Kurosawa. With an honourable place in the history of Japanese horror on account of his two most widely admired films Onibaba (1964) and Kuroneko (1968), and with several key works available on DVD, Shindo’s international fame seems secure.

But a few months before Shindo turned 100, another centenary had passed almost unnoticed on the international scene. Yoshimura Kozaburo (1911-2000) was not only Shindo’s contemporary but also his close collaborator, yet he remains barely known in the West.

When the two men first worked together in 1947, both were already established in the film industry. Shindo had been an art director, screenwriter and assistant director, most notably to Mizoguchi, with whom he worked on The Straits of Love and Hate (1937) and The Loyal 47 Ronin of the Genroku Era (1941-2). At Shochiku, meanwhile, Yoshimura had been assistant director to Shimazu Yasujiro, pioneer of the shomin-geki (films about the lower middle classes). Having directed his first film in 1934, he achieved a major commercial hit with the melodrama Warm Current (Danryu, 1939), which won him his first mention in Kinema Junpo magazine’s annual Best Ten critics’ poll.

But it was from Shindo’s script that Yoshimura directed his first genuine masterpiece, The Ball at the Anjo House (Anjo-ke no butokai, 1947), which scooped the no. 1 slot in the Kinema Junpo poll. The story of a once wealthy house in decline echoes Chekhov and prefigures the sombre mood of Satyajit Ray’s The Music Room (1958).

Shindo Kaneto (left) and Yoshimura Kozaburo

Despite these parallels, however, the film is urgently engaged with social issues directly confronting a defeated Japan under US occupation. Its subject is the decline of the pre-war upper class, and its context is the policy of land reform and redistribution implemented by the new regime. Also central is the generation gap: while the father of the house tries vainly to preserve the past, it is his daughter Atsuko (Hara Setsuko) who represents hope for the future – and suggests possible ways forward for post-war Japan.

Shindo’s concise, intelligent script was as vital to the film as Yoshimura’s uncharacteristically flamboyant direction. Shindo went on to script most of Yoshimura’s major films, and is unarguably responsible for many of their narrative virtues. Yoshimura gratefully acknowledged Shindo’s contribution, modestly observing: “Because I understand my limitations, it is necessary for me to rely on outside help.”

The collaboration between the two men deepened when they left Shochiku to set up an independent production company, Kindai Eiga Kyokai. Here, with Yoshimura sometimes serving as his producer, Shindo himself began to direct, making his debut with a semi-autobiographical story about a screenwriter, Story of a Beloved Wife (Aisai monagatari, 1951).

In their different ways, both Yoshimura and Shindo were to explore the social and political issues confronting Japan at a time of dramatic change, when the nation was obliged to take stock of its recent history. The trauma and tragedy of the Pacific War had particular relevance for Shindo. Conscripted as part of a unit of 100 men, he had been one of only six of these not to see active service; the other 94 were all killed.

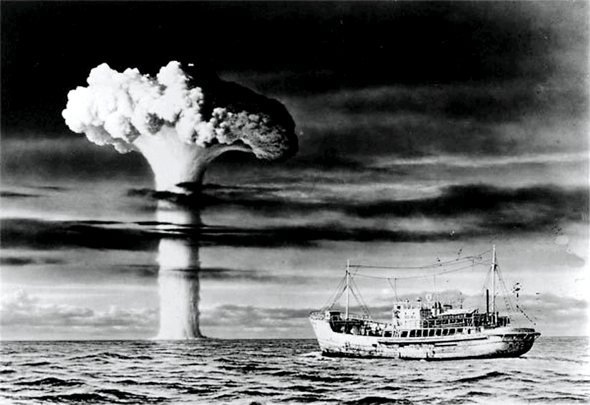

Lucky Dragon No. 5 (1959)

As a native of Hiroshima, moreover, he had a particular personal investment in the subject matter of Children of Hiroshima (Genbaku no ko, 1952), the first film to dramatise the atomic bombing of the city. This pacifist work was commissioned by the left-wing Japan Teachers’ Union, which later condemned the director for having made it “a tearjerker and destroyed its political orientation”. But it remains one of Shindo’s most moving films, and a testament to the anti-war spirit that took root in Japan after its defeat.

Shindo continued with explicit socio-political commentary in Epitome (Shukuzu, 1953), a grim geisha story; The Gutter (Dobu, 1954), a searing account of urban poverty; and Lucky Dragon No. 5 (Daigo fukuryu maru, 1959), a sombre account of the sufferings of a crew of tuna fisherman afflicted by radioactive contamination in the aftermath of US nuclear tests on Bikini Atoll.

Although these films were well received by many critics, they made little money, and Kindai Eiga Kyokai was facing bankruptcy by the time Shindo made – on a minimal budget – the film that restored its fortunes: The Island (Hadaka no shima, 1960). With its sympathetic chronicle of peasant life, beautiful locations in Japan’s Inland Sea and a plaintive score by Hayashi Hikaru, the film won fans both at home and abroad, scooping the Grand Prize at the Moscow Film Festival. It enabled Shindo to sustain his career as an independent filmmaker, and he went on to make Mother (Haha, 1963), another story about the legacy of Hiroshima.

Yoshimura also directed on occasion for Kindai Eiga Kyokai. Cape Ashizuri (Ashizuri misaki, 1954) is a trenchant account of the repression of liberals in the era of pre-war militarism. In its explicitly political theme and forceful style, it seems closer to Shindo’s own directorial work than to the majority of Yoshimura’s films, which emerged from within the studio system.

Clothes of Deception (1951)

In 1951 Yoshimura had approached Daiei in order to realise – again from Shindo’s script – his outstanding study of women in Kyoto’s Gion district, Clothes of Deception (Itsuwareru seiso). Once at the studio he went on to work on a number of prestige projects, such as the lavish 1951 adaptation of the Heian-era prose classic The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari), commissioned by Daiei to celebrate the studio’s tenth anniversary and supervised by respected novelist Tanizaki Junichiro, who had translated Murasaki Shikibu’s original 11th-century text into modern Japanese. Yoshimura won critical acclaim, and the film became Japan’s biggest commercial hit up to that date.

But it was Clothes of Deception that initiated Yoshimura’s most characteristic vein. This geisha story is often described as a loose remake of Mizoguchi’s pre-war masterpiece Sisters of Gion (1936), but this is inexact. Whereas in Mizoguchi’s study of two sisters, both women had been geisha, in Yoshimura’s film only Kimicho (Kyo Machiko) is, while her sister works in the Kyoto tourist office. Juxtaposing a traditional Kyoto profession with a modern one, Yoshimura shows how life in the old capital was changing in the wake of wider transformations in Japanese society.

All the same, the emotional register of the film is not dissimilar to Mizoguchi, with whom Yoshimura was often compared. Indeed it was Yoshimura who would take over direction of Osaka Story (Osaka monogatari, 1957), the film left unfinished by Mizoguchi on his untimely death. And Mizoguchi’s influence was apparent in Yoshimura’s sympathetic engagement with the trials of women: Clothes of Deception was the first in a remarkable sequence of films about working women in Japan’s old capital, Kyoto.

Sisters of Nishijin (Nishijin no shimai, 1952) traces the decline of traditional industry in Kyoto’s main textile-making district. Night River (aka Undercurrent/Yoru no kawa, 1956) shows a woman embarking on an affair with a married scientist while working in the profession of kimono dyeing and design. Later, Okada Mariko starred in the moving A Woman’s Uphill Slope (Onna no saka, 1960), which again focuses on a woman facing romantic difficulties while working in a traditional profession – this time sweetmaking.

Night River (1956)

Taken together, these films are not only Yoshimura’s finest achievement, but one of the Japanese cinema’s richest and most complex accounts of social change, the position of women in the new Japan, and the conflict between tradition and modernity. Yet the rest of Yoshimura’s rich and varied output should not be overlooked. In Women of Ginza (Ginza no onna, 1955) and Night Butterflies (Yoru no cho, 1957) he dramatises with equal adeptness the lives of geisha and bar hostesses in the new capital, Tokyo.

During the Occupation, he made the period film Ishimatsu of the Forest (Mori no Ishimatsu, 1949), which in the words of critic Kyoko Hirano “denounced in a satirical comedic style the useless vanity of yakuza loyalty”. The Beauty and the Dragon (Bijo to kairyu, 1955), by contrast, was described by Joseph Anderson and Donald Richie as “the only successful film version of the kabuki ever completed”.

New styles

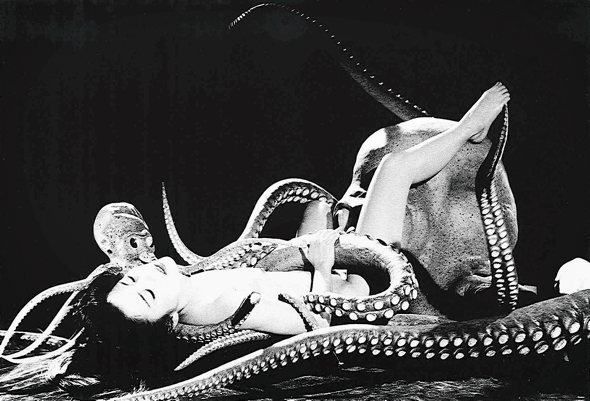

Shindo too repeatedly sought to explore new genres and styles. In the mid-1960s he realised two fine essays in the supernatural, Onibaba and Kuroneko. Both dramatically intense and visually splendid, these remain his most famous films abroad – a status no doubt sustained by the recent international interest in Japanese horror. But despite their generic novelty, they retain the social consciousness that characterised Shindo’s earlier work, finding horror in the class divisions of feudal Japanese society. Left-wing critic Joan Mellen has gone so far as to call the films “paeans to the strength of the peasants whose history the chronicles of the exploiting few have sought to deny and suppress”.

The increasing erotic content of these and other works by Shindo in the 1960s was also given social implications. As Mellen wrote: “At their best, Shindo’s films involve a merging of the sexual with the social. His radical perception isolates man’s sexual life in the context of his role as a member of a specific social class.”

Through the 1950s and 1960s, Shindo remained an imaginative cinematic stylist with a penchant for striking imagery and an interest in formal experimentation. In Children of Hiroshima, he visualised the bombing in an intense montage sequence inspired by Soviet silent cinema. The Island, made without dialogue, conveyed its meaning solely through the body language of the actors, the sound effects and music, the use of landscape and the position of the camera. In Onibaba and Kuroneko, his flamboyant direction was complemented by Kuroda Kiyomi’s stunning chiaroscuro cinematography and Hayashi Hikaru’s menacing scores.

Onibaba (1964)

Yoshimura’s style, by contrast, was generally simpler and more classical. In his early years, inspired by German silent-era master F.W. Murnau, he adopted a somewhat experimental camera style, traces of which remain in the occasionally baroque technique of The Ball at the Anjo House. But subsequently, under the influence of William Wyler, he moved away from experimentation towards an understated, more conventional mise en scène.

Yet if the style of his mature work in the 1950s is less distinctive than that of some of his contemporaries, Yoshimura was a master storyteller. His attention to nuances of characterisation and subtleties of emotion was matched by his ability to shape compelling, coherent narratives through the choice of camera position and camera distance.

Primarily a studio filmmaker, Yoshimura’s work declined – perhaps inevitably – as the norms of the Japanese film industry altered during the 1960s. Bamboo Doll of Echizen (Echizen take ningyo, 1963) still showed some of his old talent but, beset by ill health, he made fewer films of real value. Nevertheless, his last work, the independently produced The Tattered Banner (Ranru no hata, 1974), earned him a final ranking in the Kinema Junpo Best Ten. In 1976, after his retirement, he was awarded the Medal of Honour with Purple Ribbon, given by the Japanese government for distinguished contributions to the arts.

Portraits of the artist

There was no stopping Shindo, however, who was to work prolifically through the subsequent decades and into the 21st century. His style grew less showy, simpler and more classical, but his thematic concerns showed an increasing self-consciousness, with a recurrent interest in artist figures that recalled the themes of his debut, Story of a Beloved Wife. He paid tribute to his mentor Mizoguchi in a 1975 documentary, while in The Life of Chikuzan (Chikuzan hitori tabi, 1977) he retold the harsh youthful experiences of Chikuzan Takahashi, a shamisen player from northern Japan who became a cult figure in later life. The film intercuts live concert footage of the middle-aged Chikuzan with dramatised reconstructions of his youth.

Edo Porn (1981)

Shindo’s later artist portraits include Edo Porn (Hokusai manga, 1981), an iconoclastic biopic of the celebrated 19th-century woodblock artist Hokusai; The Strange Story of Oyuki (Bokuto kidan, 1992), about the writer and flâneur Nagai Kafu, who had chronicled Tokyo’s interwar demi-monde; and another documentary, Sakuratai chiru (1988), examining the lives and work of the members of a left-wing theatre group who perished at Hiroshima.

Unsurprisingly for a filmmaker active into his nineties, Shindo has also addressed the topic of old age, most centrally in The Last Note (Gogo no yiugonjo, 1995). For this he marshalled a superb veteran cast, including the poignant last appearance of his wife and regular star Otowa Nobuko (a fixture in his films as far back as his debut, the aptly named Story of a Beloved Wife); she died of cancer only days after shooting was completed. Shindo himself, however, kept working. In his last film Postcard, directed from a wheelchair, he revisited the legacy of the Pacific War, which remained the defining lifetime trauma for his generation of Japanese.

In old age, Shindo became something of an institution: he was pronounced a person of cultural merit in 1998, was awarded the Order of Culture in 2002 and won the Japan Academy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2003. At his 100th birthday celebrations, his granddaughter Shindo Kaze – herself an active filmmaker – declared: “My grandfather hopes that his works will endure for a long period of time.”

And indeed, at their centenaries, the films of Yoshimura and Shindo remain both fascinating and moving. Living through some of the most turbulent times in Japanese history, they sustained careers spanning war, occupation, and the post-war years of prosperity and modernisation. Their films chart the experience of those times, and constitute a valuable historical record of life in 20th-century Japan. But their importance is not only historical. Both men were compelling dramatists and filmmakers of profound compassion and humanity. It is time to celebrate their joint and separate achievements.