Sarah Polley’s first directorial feature Away from Her (2006) told the heartbreaking tale of a long-married couple pondering their fidelity to each other as the wife’s memory was gradually swallowed up by early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. By contrast the marriage slowly unravelling in Take This Waltz belongs to 28-year-old bohemians Margot (a characteristically charismatic Michelle Williams) and Lou (an uncharacteristically sombre – and moving – Seth Rogen).

She is some kind of freelance copywriter; he writes cookbooks exclusively about chicken. Five years into matrimony and well past love’s first spring, the pair are entering – both literally and metaphorically – a sweltering, sticky summer. The down-at-heel yet up-and-coming Toronto neighbourhood they inhabit is saturated in colour, bathed in a shimmering heat haze. At night the air is as close as their tangled limbs.

Which is to say, too close: Margot is slowly suffocating in the swampy bosom of Lou’s large, garrulous family (whose effusive, cloying tactility is beautifully captured, Cassavetes-style, during a family meal). Confused, she pushes and pulls, switching between ill-timed attempts at adult seduction, teasing teenage banter and childishly whimpering “I wuv you” like a kind of prayer for acceptance.

Whether the flirtation she embarks on with neighbour Daniel, a lanky artist-cum-rickshaw-driver, is symptom or cause of her relationship’s breakdown is hard to tell: Luke Kirby’s character is little more than a beautiful, balletic cipher, his lack of friends or family making him a perfect receptacle for Margot’s doubts and longings. Indeed, one might speculate about whether he’s even real.

If the coincidence of Daniel and Margot’s meet-cute – having exchanged neat barbs during a business trip they are seated next to one another on the plane home, before discovering that they live on the same street – seems somewhat far-fetched, elsewhere too the film stretches the limits of credibility. At the film’s close we certainly seem to slip into fantasy, as Margot whirls and spins alone on a fairground attraction. The dialogue also takes on a phony air at times, the subtext barely masked by stagey lines such as Margot’s admission to Daniel, referring to air travel, that “I’m scared of connections.”

The film’s trappings are occasionally a little gauche, then. And this isn’t helped by the too-cool urban-hipster set-up, all kitsch chintz, clutter and quirk (the gamine Margot only drinks milk or martinis, and feigns illness at airports to mask her neuroses). But at the film’s heart are some brutal insights into female ageing and subjectivity. Showering after a session of aquarobics, Margot’s lithe body is starkly contrasted with the naked forms of her fellow swimmers – all pubes, boobs, bellies and cellulite – suggesting a sense of ripeness turning to decay.

A girl-woman who committed to marriage age 23 but at 28 sees a pet as a step too far; whose husband thinks nothing of kissing her while she’s on the loo but who closes his eyes when he talks to her: small wonder that Margot is so readily seduced by the possibility of being desired, of being seen. The scales first tip in Daniel’s favour when he describes in intricate detail exactly how he would make love to her, beginning with the tender detail that “I’d kiss each of your eyelids, and then your birthmark.” Compare that to Lou’s devastating throwaway remark: “I don’t need to ask how you are. I spend every day with you.”

Williams gave a powerful performance as a disillusioned working-class wife in Blue Valentine (2010). Although Polley’s film is far less gritty, Williams arguably outdoes herself here. Solipsistic, self-absorbed, the girl who has it all and yet still isn’t satisfied, Margot could easily have been a very unlikeable character (there are unkind names for girls who behave towards men like Margot does, and tease is the least of them).

Instead, she emerges as the film’s victim. A montage of passing months shows her and Daniel moving through various sexual positions and partners, threesomes and foursomes and eventually ending up exactly where the film started. For all the sense of possibility and potential, of doubt and regret, the wheel of fate turns and Margot lands in the same place every time.

In many ways, Margot is a modern day Blanche DuBois, implicitly echoing the latter’s cry that “I don’t want realism… I want magic! Yes, yes, magic!” Yet ultimately, the bittersweet truth of Polley’s beautiful film is that it’s inevitable: no matter who we love, we are always ourselves, and with it we are always alone.

-

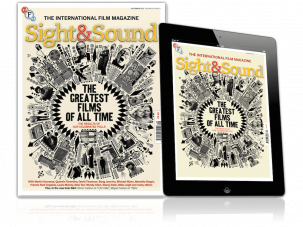

Sight & Sound: the September 2012 issue

In our redesigned, expanded new issue: The Greatest Films of All Time by 846 critics and 358 directors. Plus more pages, sections and columns, and...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.