Spoiler alert: this review gives away a plot twist

Even as M, fighting to keep her job and protect the service, quotes Tennyson’s Ulysses – “though we are not now that strength which in old days moved earth and heaven” – to a hostile parliamentary committee, Bond runs down Whitehall to rescue her from a vengeful assassin, her words – “weak by time and fate, but strong in will” – continuing over the chase.

Bond, like Ulysses, is “a part of all that I have met”; Skyfall, without breaking the new cycle begun by Casino Royale (2006), is also a pivotal episode in the 60-year cross-media, multi-author odyssey begun by the novel of the same name. Much has Bond seen and known in that time, “cities of men and manners, climates, councils, governments”, but almost none of his previous screen adventures have taken place in his native land. In Sam Mendes’s first Bond movie, dazzlingly photographed by Roger Deakins, the sequences shot in wintry London and Scotland stand out.

USA/United Kingdom 2012

Certificate 12A 142m 58s

Director Sam Mendes

Cast

James Bond Daniel Craig

Gerardo Rodriguez, ‘Raoul Silva’ Javier Bardem

Gareth Mallory Ralph Fiennes

Eve Naomie Harris

Severine Bérénice Lim Marlohe

Q Ben Whishaw

Kincade Albert Finney

M Judi Dench

Patrice Ola Rapace

Bill Tanner Rory Kinnear

Dolby Digital/Datasat/SDDS

In Colour

[2.35:1]

Distributor Sony Pictures Releasing

Bond has returned gaunt and out of shape, assumed dead after a failed operation in Turkey, to no wife and no son, but to guard the woman who caused him to be shot. In Fleming’s Diamonds Are Forever, Bond says that he is “almost married” to M, but neither Fleming nor his Bond could have countenanced a woman in charge. Daniel Craig’s Bond, as Vesper Lynd guessed in Casino Royale, is an orphan, and in Skyfall Judi Dench’s M is his adoptive mother. It is her dedication to the service that leads to Bond’s near-death, and her antagonist, agent-turned-cyber-warrior Raoul Silva, acts on matricidal emotions that Bond himself represses. Yet whereas in her first appearance, in GoldenEye (1995), Dench’s M called 007 a “relic”, her climactic speech here is a defence of “human intelligence” in the age of Stuxnet.

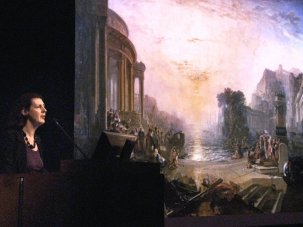

Absent from the first Craig outings, Q, played here by Ben Whishaw in fine comic geek mode, is one of the doubters; like Silva, he can inflict damage enough via fibre-optic cable but supposes that “every now and then a trigger has to be pulled”. He first meets Bond at the National Gallery, in front of Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire, apparently just in order to draw a parallel between the scrapyard-bound warship and his obsolescent colleague. Bond sees only “a bloody big ship”, conceivably a reference to Bond scholar Kingsley Amis’s interpretation of Jaws – “about being bloody frightened of being eaten by a bloody great shark” – and a reminder that Bond is not only ‘about’ early-Victorian cultural references. It’s also a cocktail of beautiful women, fancy cars, swank hotels, explosions, aircraft, chases, brands, shootouts, ‘a series of exotic locations’, gadgets, gambling, gags, the Bond theme, villains and their lairs, patriotic sentiment, and cocktails.

While these fundamentals have stayed constant over half a century, the franchise has long oscillated between the gargantuan – You Only Live Twice (1967), Moonraker (1979) – and the supposedly more sober – On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), For Your Eyes Only (1981). Skyfall follows the pattern in reaction to the excessively pared-down, low-stakes and joke-free Quantum of Solace (2008).

Deakins’s camerawork, free of the Bournian cutting that beset Quantum, is the most striking instance of a general change. Craig’s moodiness has been softened by the reintroduction of Q and Moneypenny, incarnated by Naomie Harris and given an origin story, while Javier Bardem as Silva is the most authentically Bondian Bond villain in decades: outrageously camp, inhabitant of a deserted island and, after an accident involving service-issue cyanide, afflicted by what Amis called the villain’s sine qua non, “extreme physical grotesqueness”.

Not everything works. Adele’s retro theme, though a lyrical catastrophe, is still an improvement on the woeful Chris Cornell and Jack White-Alicia Keys tracks, but there hasn’t been a great Bond score since The Living Daylights (1987), John Barry’s last.

Like its two predecessors, Skyfall ends with a new beginning. Dench’s M has been replaced by Ralph Fiennes’s old-school ex-agent, and HQ has been returned from the eyesore on Vauxhall Bridge to the old offices of Universal Exports. Craig’s Bond has gone from new recruit to near-has-been in three films; but in this case one doesn’t want consistency. The formerly chippy Bond winds up almost chipper, and ought to stay that way. Mendes has blown up Bond’s family home as well as the service’s, and less angst-ridden adventures seem to be in the offing. The Oscar-winning former artistic director of the Donmar Warehouse has proved himself well up to the task.

-

Sight & Sound: the December 2012 issue

Paul Thomas Anderson on The Master, Cristi Puiu on Aurora, Thomas Vinterberg on The Hunt and LFF newcomer Sally El Hosaini on My Brother the Devil ...

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.