Festival blog | Web exclusive

No (2012)

Film of the day

You might think that a director is playing with fire by calling his film No, especially in Cannes where critics eagerly embrace any opportunity for a smarmy put-down. Pablo Larraín needn’t worry. Applause and cheers for the final instalment of his trilogy about the Chilean dictatorship lasted well after the lights had gone up here, leaving the filmmakers on stage with nothing to do but clap back.

It was well merited, and makes one wonder why this isn’t in Competition. Larraín has serious form, and his film is at once worthy, skilfully made and hugely entertaining – a rare combination that eludes many a po-faced festival entry.

With Tony Manero, Larraín presented a unique perspective of life in the midst of Pinochet’s dictatorship; in Post Mortem he cast back to the regime’s beginning, and the coup itself; now he looks to its unexpected demise. Coinciding with the obviously more upbeat message, he’s made his closest yet to a crowd-pleasing, mainstream movie.

In 1988, Pinochet was forced by the international community to make some show of democratic reform. His sly concession was to call a referendum on whether or not he should remain in power for a further eight years. For the first time, opposition parties were granted air-time to voice their views. But no-one believed it would make a difference. It was felt that Pinochet could win even without cheating, because of what one character in the film calls the “learnt hopelessness” of the people. They simply wouldn’t bother to vote.

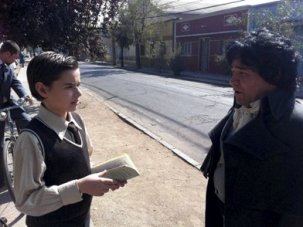

Larraín and writer Pedro Peirano (who scripted the fantastic The Maid) tell the tale of how the No campaign defied those predictions. Their central character, played by Latin cinema’s go-to hero Gael García Bernal, is René Saavedra, an amalgam of two of the men most instrumental in the No campaign. He is a terrific creation, a skateboarding ad man who we first meet presenting his advertisement for a fizzy drink called, with brilliant irony, It’s Free. When he wants to get a kiss out of his ex-wife, a radical campaigner, he simply uses the word ‘Allende’.

The genius of René’s No campaign is to take the frivolous and superficial tropes of advertising and apply them to the referendum. Much to the horror of the opposition parties who have engaged him, he doesn’t want to preach about the disappeared, or the fact that millions live in poverty – the country’s misery, he says, “won’t sell”. He wants to talk about “happiness”.

The comedy in Larraín’s earlier films was pitch black. Now, befitting its more upbeat historical moment and the sheer jolliness of the No campaign, it is much broader. In fact, it’s as if the director is applying René’s maxim, “a little lighter, a little nicer”, to himself. Even Alfredo Castro, the sinister star of the previous films and firmly in the Yes camp, gets to let his hair down. At the same time, we’re left with no doubt what’s at stake. People are constantly speaking in whispers and in public spaces; René, his family and colleagues are stalked by men in unmarked cars. Much of the feel good vibe is due to our witnessing a country coming out of the shadows.

In a stylistic masterstroke, Larraín shot his film with a 1983 U-matic video camera, so that there’s virtually no difference between the copious archive footage and the new. It’s a seamless whole, and an enormously satisfying one.

← Previous: The wrong earlobes: The Imposter | Next: Nuns on the verge of a nervous breakdown – Cristian Mungiu’s Beyond the Hills →