from our July 2012 issue

There’s a moment halfway through Alfred Hitchcock’s 1929 film Blackmail (in its silent version) when the heroine Alice (Anny Ondra), still dishevelled from her all-night walk home after murdering a would-be rapist, sits on her bed and racks her weary brains for a way out of the nightmare. We see her looking at herself, expressionless in the dressing-table mirror, then looking up at the wall behind it – and seeing the photograph of her boyfriend Frank (John Longden). We know Frank is a detective (although in the photo he’s a uniformed constable – their relationship goes back a long way) and we also saw them part on bad terms. But from the dawning light in her eyes, we understand that Frank is the only person she can trust to help her.

Alice throws on her clothes as fast as possible, turning before our eyes from night-time diva into daytime dutiful daughter (the second time in 15 minutes that Hitchcock has let us watch her undress). But in solving the immediate problem of where to get help, Alice has also given herself further obstacles to overcome in getting to Frank without her parents getting wind of what has happened. In creating an opportunity for escape, she has let herself in for more suspenseful action.

It’s a beautifully handled sequence, no more than 40 seconds in total, solving so many narrative problems with a couple of looks and a photograph while drawing us seamlessly into the second act of the drama. But it so desperately needs music to help it make its impact. Watching the sequence in silence we will certainly understand the train of thought it evokes, but we will still be outside observers, coolly following Hitchcock’s paper trail to primarily intellectual conclusions, which we as audience members may reach at different speeds.

With the right music, however, we can become Alice, be inside her skin, feel her desperation and share communally the exact moment at which the world changes for her and she glimpses a chink of light down the tunnel. We go from being observers of the action to being willing participants – as is always the intention of Hitchcock’s voyeuristic camera. The sensory gaps left by silent cinema will be filled in with music strong enough to make an impact, but hopefully discreet enough that the audience won’t register the extent to which they are being manipulated.

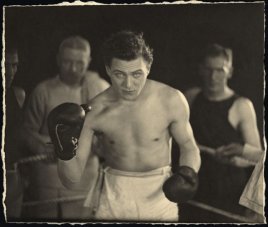

Director Alfred Hitchcock on set with lead actress Anny Ondra directing the now better-known sound version of Blackmail

Hitchcock and Anny Ondra on set of the sound version of Blackmail

In 1933, Hitchcock gave an interview to the distinguished industry publication Cinema Quarterly, specifically dealing with music and film, and related to his discoveries while making Waltzes from Vienna that year. In it he remarked:

“Film music and cutting have a great deal in common. The purpose of both is to create the tempo and mood of the scene. And, just as the ideal cutting is the kind you don’t notice as cutting, so with music… I think cutting has definite limitations. Its best use is in violent subjects. That is why the Russians made such effective use of it, because they were dealing with violence, and they could pile shock on shock by means of cutting… But if I am sitting here with you discussing the Five Year Plan, no amount of cutting can make a film of us dramatic because the scene is not dramatic. You cannot achieve quiet, restrained effects that way. But you might express the mood and tone of our conversation with music that would illuminate or even subtly comment on it.”

It’s an obvious point to make, but in scoring silent films the music is all the sound there is – an enormous luxury for a film composer used to competing dialogue and effects tracks. And there’s guidance to be had from Hitchcock’s words – music as cutting is a good way to look at silent-film scoring. The score will speed up action, slow it down, point up elements of the drama, draw us into the action and make its own statements at the same time as Hitchcock’s, but with subtle differences. The narrative ‘road map’ is the same for visuals and music, but they are not in the same car.

In my own mind, at least, I have ‘worked with Hitchcock’. The Blackmail score I composed in 2008, and which I am performing again in London this month, may have arrived late for the party, but I hope that, in composing it, I have consciously emulated what Hitchcock demanded his art should be – pure cinema. My inspirations were three-fold: first, the film itself, which speaks volumes with every shot; next, such understanding as I could manage of Hitchcock himself from interviews, biographies and his other movies – this, to me, was particularly important; finally, there’s the ‘Hitchcock score’ which – despite the fact that he worked with numerous composers during his sound career – undoubtedly exists as a style in itself.

So often, the modern TV shorthand for Hitchcock is the classic profile accompanied by Bernard Herrmann’s theme from Vertigo (1958) – the director’s entire oeuvre summed up in those menacingly circling arpeggios. Herrmann’s North by Northwest (1959), Psycho (1960) and Marnie (1964), Miklós Rózsa’s Spellbound (1945) – these scores are symphonically planned, orchestrally and harmonically complex, tinged throughout with darkness and dread.

As a young student listening obsessively to records of Hitchcock scores in the 1980s, I heard the unmistakeable sound of 1950s Hollywood: the tightening of the screw in the suspense scenes, the self-referential tension and thrill motifs which soared romantically in the love scenes – but always carried just a hint of warning that there might be no happy ending. In landing the dream commission of tackling the silent Blackmail, I felt I needed all the help I could get to reach the heights attained by the Master. Utilising the musical approaches that Rósza, Herrmann and Franz Waxman (Rebecca, Rear Window) brought to Hitchcock’s work gave me the advantage – I consciously stood on the shoulders of these great Hollywood composers to look Hitch in the eye.

Hitchcock famously shot Blackmail in both silent and sound versions, but I have always preferred the former. By 1929 Hitchcock was a master of the techniques of silent cinema; sound made him a pioneer – albeit a hugely gifted one – enmeshed in the new medium of hissing soundtracks, cut-glass accents and iconic sound illusions (“Knife… KNIFE!!”) which are the opposite of “the music you don’t notice”. The sound Blackmail is ground-breaking, clever, chilling, with a perfectly serviceable score. But the silent version is, for me, the greatest British silent film: a mature and adult drama, swift, deft and complex, all in all a more rewarding experience for a modern audience than its sound counterpart.

In dealing with silent films as a live pianist, my approach to silent film has always been to treat the music as a bridge between the age of the film and the age of the audience. Modern audiences are used to 80 years of film music, synchronised effects, detailed sequential scoring and genre references which have evolved over the lifetime of sound cinema. In bringing these elements to bear on pre-sound cinema, I hope that I am providing an atmosphere in which the audience can relax into the film, secure that at least the sound world they inhabit is familiar.

Blackmail has been in my consciousness for over 20 years. It was one of the first British pictures I accompanied, at a memorable BFI summer school on early British film in Stirling in 1989. It still amazes me to this day that the silent Blackmail is so little known in comparison with its sound counterpart; indeed, in a world in which a badly transferred 16mm dupe of the silent version is offered as an extra on the German DVD of the sound version, I feel that celebrating the silent version with a full orchestral accompaniment ignites the silent/sound debate in a wonderfully immediate way.

Silent film remains the poor relation of its sophisticated offspring for many, particularly those in the media who should realise the difference. Perhaps one day soon silent cinema, to the broad mass of even the culturally aware, will at last come to be recognised for what it is – not sound film with the sound turned down but a theatrically vibrant form of cinema in its own right. As opera is to theatre, silent film is cinema with the emotions musically engaged – not a negation of reality but an emotionally enhanced version of it.

Among the British silent-movie treasures I encountered in Stirling that summer, Blackmail stood out for many reasons. First of all, it’s drenched in the character of London, my home town, and its peculiarly British (specifically English) attitudes, few of them particularly wholesome – all character quirks I grew up with and recognised. Hitchcock’s own character is an amalgam of a good Catholic’s attitude to sin (guilt and retribution) and a good Londoner’s attitude to crime (quiet fascination with those who effortlessly practise it and outright delight at those who stylishly get away with it). Blackmail was, at this point in his career, his most definitive statement of his own character. While accompanying the film I fell in love – like Hitch – with Anny Ondra, and tried to make the music complicit in her seduction; I also tried to mirror Hitchcock’s love of London, its vulgarity and its people (always excepting its policemen).

Then there’s the film’s moral maturity. Unlike so many of the silents I experienced in my early performing career, Blackmail demands no stark choice between good and bad. Hitchcock revelled in the shades of grey in human behaviour. Here he gives us an antiheroine and a credible, shabby, almost sympathetic villain in the shape of her blackmailer Tracy (Donald Calthrop); a flawed knight errant and the cosy, salt-of-the-earth Londoners around them – all at the mercy of the machinery of a rule of law that recognises only the scumbags in its mug-shot books and saunters idly by while sexual violence is taking place three floors above. Hitchcock had never before been as subversive as when he separates his flighty heroine from her boring beau, makes us cheer as she gets the good time she’s after with the exotic artist, then sends her careering back to her besotted detective with the artist’s blood on her hands, infectious with the virus of shared guilt.

Famously, Hitchcock wanted an ending for the film that mirrored the opening – with Alice going through the arrest procedure and Frank departing for an evening alone – but the ending foisted on him is much more chilling. As Frank and Alice walk, stone-faced, down the corridor of Scotland Yard, we can see the burden of complicity that they both now carry, the possibility of their expiation painful and long-lasting. Alice may have avoided the noose we have seen in shadow around her neck, but in doing so she has condemned them both to a lifetime of guilt and shame. Hitch the Catholic inadvertently won the day over Hitch the cynic – and he must have been laughing all the way to the premiere.

Grey areas

When the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna approached me to score Blackmail for the Orchestra of the Teatro Comunale, I found myself in the same privileged position as my Hollywood composition heroes: that of working with the best director in the business towards a classic romantic orchestral score in the old tradition, where tonality seldom enters pure major or minor keys but lurches between the two, matching the characters’ flailing moral choices. As Blackmail delights in the grey areas of human behaviour, my score attempted to embody equally alluring shades of grey.

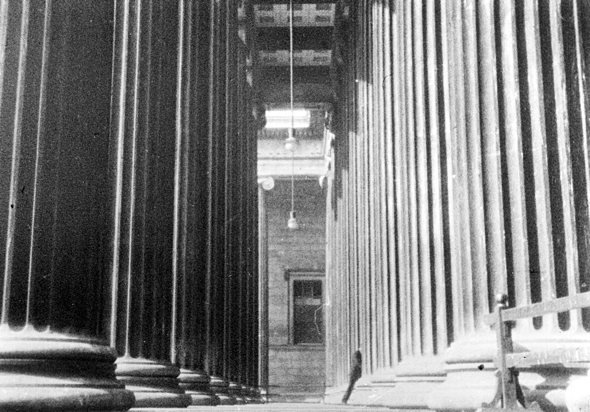

Blackmail: outside the British Museum

My love of the noir scores of Rózsa and Waxman (Double Indemnity, Sunset Blvd. et al) had taught me how their tonality – built on full and mouth-watering seventh, ninth, eleventh, thirteenth chord shapes – could mirror the moral complexity of the dramatic journey. Chords in those teetering towers of notes become neither major nor minor but somehow both, slipping equally easily into sunny major chords or foreboding minor ones. The melody lines, love themes and action motifs that negotiated the shifting tonalities beneath breathed life into Hitchcock’s silent classic – albeit life it could never have known in its time. But then I never pretend to be writing music that is contemporary with silent films themselves. These movies are there to be translated for a modern audience, not embalmed.

Even dead directors – the good ones anyway – can make their musical requirements abundantly clear through superb, unambiguous direction. Blackmail’s opening police-procedural sequence stands alone, unfolding at top speed from the first frame, working the suspense of darkened staircases and corridors, chuckling along with jovial digs at the cops and ending with amusing musical formality as the spyhole in the prison door is slammed shut on a foul-mouthed malefactor. I packed this sequence full of musical ideas (hommage to Herrmann in the chase, bass clarinet under vibes as the police traverse the darkened corridor, slowly drooping strings to match the hunted man’s hand movement towards the gun), culminating in a po-faced ‘march of the CID’ which I’d like to think Hitch would have smiled at.

I hadn’t had the luxury of a symphony orchestra to play with before, but I had heard a lot of film scores and I found the palette it offered solved so many problems. With piano, the statements you wish to make can only be achieved with changes or accents of tempo or tonality; now a small effect could be signalled with a lead instrument, without interfering with the basic structures. I usually introduced my tunes lightly, carried by a solo instrument, to be repeated in full with massed strings or vibrant horns; always I tried to make the transitions from thought to thought as smooth and imperceptible as possible.

But when appropriate, I did consciously break across the music, engineering a complete collapse of all musical tonality immediately after the murder (which of course had to be accompanied by Psycho-style slashes in the strings), preferring instead tightly packed discords of high, legato strings moving slowly and unpredictably under the emergence of a bloodstained Alice – like the ringing in one’s ears after a loud noise. By her actions, the world has irrevocably changed, and so the music either side of that traumatic event is completely unconnected.

Her haunted walk through milling West End theatregoers was the easiest section to score as it was a situation I had seen before countless times in Hitchcock’s films – the loner who has committed a crime that separates them from society walking through that society carrying a burden that only they and we recognise. The pace of her steps even set the tempo.

A similar feeling, as if Hitchcock were telling me how to do it from across the decades, struck me when it came to scoring the film’s climactic chase, as Tracy barrels through the British Museum to his fate high above the Reading Room, and Alice stares unseeingly at her guilt unfolding – like Macbeth’s daggers – before her eyes, finally standing up to receive the shadowy ‘noose’ that she knows now awaits her. Even there, thanks to the precision of his pacing, I felt Hitchcock ‘directing’ the music to its climax, not on Tracy’s despairing cry but on Alice’s symbolic ‘execution’.

Except that the film doesn’t end there. The hardest sequence to score turned out to be Alice and Frank in the superintendent’s office. There’s no way this scene can be anything but an anticlimax, but I brought all the emotional and cathartic weight I could to their final walk down the corridor of Scotland Yard. I had consciously left my big ‘shared guilt’ theme incomplete – hinted at in miniature in the title music, but only finally coming to full maturity in these closing seconds before turning into a thunderous major-key finale over the end titles, as if Hitch were saying: “Goodnight. Don’t have nightmares.”

Frank and Alice walking away at the finale of Blackmail

I scored the music sequentially and chronologically over about two months, and enjoyed the experience more than I thought possible. It is a truly great film, generous in its insights, its pacing, its surprises – not a second of its running time is wasted. How much my score has done to support it is for others to judge, but at least people will know that before there was sound, there was Blackmail – and a hinterland of silent wonders that have been too long ignored.

Parts of this article first appeared in the journal ‘Soundtrack’. Neil Brand’s score will be performed live at an outdoor screening of the restored silent version of ‘Blackmail’ on 6 July at the British Museum, London, as part of the BFI’s major ‘Genius of Hitchcock’ season. He will also be discussing Hitchcock’s use of music on 20 September at BFI Southbank, London.

The BFI’s accompanying compendium ‘39 Steps to the Genius of Hitchcock’, edited by S&S’s James Bell and featuring essays by 39 eminent critics, curators, historians and filmmakers including Charles Barr, Patrick McGilligan, Laura Mulvey, Camille Paglia, David Thomson and Guillermo del Toro, is available now from BFI venues and the online Filmstore.