The opening scenes of most films intended for commercial distribution tend to ease viewers into their fictional worlds, introducing protagonists, defining the context in which these protagonists exist, hinting at experiences they will subsequently undergo. Bill Gunn’s Ganja and Hess (1973) does precisely the opposite. By the time its opening credits finish playing, we will already have read a series of onscreen texts referring in the past tense to events which have not yet occurred, heard a voiceover narration from a minor character (which also evokes future situations retrospectively), listened to a ballad which outlines the film’s supernatural mythology, encountered novelistic chapter headings, seen close-ups of paintings, watched documentary-style footage of a church service, and been subjected to a barrage of disjointed editing techniques which obscure rather than clarify – at least, that is, if we believe the clear exposition of narrative to be a sine qua non for works ostensibly outside the experimental or avant-garde traditions.

Ganja & Hess screens 29 July 2016 in the Black Atlantic Cinema Club at the Watershed, Bristol and is available on DVD and Blu-ray from Eureka Classics.

This belief was certainly the one subscribed to by Ganja and Hess’ financiers, who were so horrified by Gunn’s 113-minute cut that they hired film doctor F.H. Novikov (aka Fima H. Noveck) to reedit it. Novikov meticulously unpicked Gunn’s structure, reduced the running time to 79 minutes and changed the title to Blood Couple. Gunn disowned the result, leaving Novikov to take the director credit.

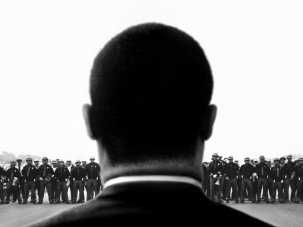

Ganja & Hess (1973)

Although it is not immediately apparent from Gunn’s version (released on DVD and Blu-ray by Eureka), Ganja and Hess’ story is relatively straightforward. Dr. Hess Green (Duane Jones) is an African-American anthropologist whose unstable new assistant, George Meda (Gunn), stabs him with an ancient wooden dagger before committing suicide. Hess finds the dagger has transformed him into an immortal being who is compelled to drink blood (the word vampire is never used). He eventually meets and falls in love with Meda’s wife, Ganja (Marlene Clark), upon whom he decides to bestow the gift of immortality.

One of the most notable aspects of Novikov’s reedit is that it renders this narrative considerably less elliptical by restoring footage Gunn had left on the cutting-room floor. After Ganja angrily announces she has discovered Meda’s corpse in the basement, the scene in which Hess explains why it is there (“I didn’t kill him. Your husband committed suicide. I swear that’s the truth.”) is unique to Novikov’s variant.

The director’s cut substitutes a three-minute sequence shot (entirely missing from Blood Couple) in which Ganja reminisces about a snowball fight she participated in as a child. Although this monologue does not appear in the screenplay, the explanation scene does. The fact that Gunn both wrote and filmed the latter (perhaps to satisfy the demands of his more commercially-minded producers) before rejecting it it in favour of an improvised aside suggests not that he was incapable of telling a straightforward story, but rather that he had something quite different in mind.

Consider this frame grab.

It is taken from an early scene showing Meda eating dinner with Hess. Meda is relating an anecdote about a director friend, an anecdote which has no bearing on either the narrative or the professional relationship of these characters. Even allowing for this, the telling of the anecdote is chaotic. Meda momentarily forgets what he was saying, has to explain in advance that linguistic ambiguity which will provide the punchline, makes a crucial error by substituting one word for another, introduces irrelevant information about a party he attended, and is repeatedly interrupted by Hess’s butler. The film might almost be providing us with a guide as to how it should be read, warning us that nothing will move straightforwardly from A to B, that digressions – even digressions within digressions – will be of greater consequence than the main narrative path.

The shot illustrated above makes use of a similar strategy. For surely the first thing we will notice is how ‘badly’ it has been composed. The two onscreen characters are crammed awkwardly into the bottom part of the image, ‘dead’ space above their heads occupying more than half the screen. It looks oddly like something from an old VHS transfer of a film made in the Super 35 format, where the entire frame of a shot intended to be masked at 2.35:1 has been exposed.

Ganja & Hess (1973)

It is worth recalling that Bill Gunn started out not as a filmmaker but as a novelist, since Ganja and Hess – which incorporates philosophy, music, painting, politics, religion, poetry, geology and anthropology – might easily belong to any mode of discourse except cinema. Judged by Hollywood norms, the shot of Hess and Meda seems almost ferociously uncinematic – which is, of course, the point. Gunn was a black auteur working during a period when American directors were predominantly white, and if we are to perceive this masterpiece’s apparent ‘flaws’ as deliberate strategies, we must view them as part of an oppositional project rooted in the need to reject a language adjudged imperialistic.

Yet Gunn’s ‘careless’ composition makes perfect sense on its own terms, terms which incorporate rather than erase its function as an anarchic gesture. In his autobiographical 1964 novel All the Rest Have Died (whose protagonist, Barney Gifford, shares the author’s initials), Gunn writes:

“I am not concerned with what I am racially. I am nothing and I am everything; I am a part and I am all. I am only concerned with what you think I am, and how it affects you and your approach to me. I do not trust labels, or names. I do not trust people who pass out titles and categories to keep racial order. I am racially disorganized, my blood had been invaded by blood that is also mine. There is no part of me that came first. I am the rapist and the raped. I am victimized and I am responsible. I bear it all and will have nothing to do with any of it. It is you, remember. It is all yours, the guilt and the pity. I am only the excuse.”

Ganja & Hess (1973)

For an artist angered by the way individuals are systematically categorised according to the colour of their skin, the human body is neither an accurate nor reliable indicator of inner states, and thus cannot be positioned at the centre of the visual world. On the contrary, it is simply the sign of another ‘system’ that must be deposed, another ‘language’ that must be rejected. If the rules of composition were created by, and in the name of, ‘white’ interests, it will clearly be necessary to repudiate them before a ‘black’ sensibility can be conveyed. Gunn is determined to overthrow all systems, including those which shape how we think about race, construct images and tell stories. As Ganja and Hess so eloquently demonstrates, before new things can be said, new ways of representing must be found.

-

The Digital Edition and Archive quick link

Log in here to your digital edition and archive subscription, take a look at the packages on offer and buy a subscription.