from our November 2012 issue

A Safe Place (1971)

Although most cinephiles fondly recall their earliest visits to the cinema, with its rapt audiences and large screens, my own memories of childhood filmgoing are generally negative: the obligatory Disney features, Saturday mornings spent watching Children’s Film Foundation atrocities and family outings which involved seeing either a James Bond film or, this being the 1970s, a disaster movie (including Jaws, now rarely discussed in terms of its relationship to the disaster cycle).

Needless to say, there were some bright spots: a revival of 2001: A Space Odyssey and a double bill pairing the Terence Hill/Bud Spencer comedy Watch Out, We’re Mad with Paul Bartel’s Cannonball (retitled Carquake). But the films that made the deepest impression were those I saw on the small screen. In part, this was due to my parents’ decision to rent a VCR in 1980, something that totally changed the way I related to moving images. Films, those ephemeral things that moved from beginning to end at their own pace before vanishing into the mists of memory, now became concrete objects – like books – which could be recorded on VHS cassettes, placed on a shelf and referred to at leisure.

Thanks to television and the VCR, I was able to view and re-view films which, at the age of 13, I’d have been ‘protected’ from theatrical exposure to. I was fortunate to be developing a serious interest in cinema at a time when the BBC functioned like an intelligently programmed repertory theatre, with retrospectives dedicated to Orson Welles, Francesco Rosi and Luis Buñuel accompanied by newly commissioned documentaries.

For me, the biggest revelation was ‘The Great American Picture Show’, a season dedicated to US films from 1969 to 1975 that appeared on BBC2 in 1980. The titles, in order of screening, were as follows: Badlands, The Conversation, Thieves Like Us, Five Easy Pieces, The Sugarland Express, Diary of a Mad Housewife, American Graffiti, Smile, The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid, Klute, Scarecrow, Electra Glide in Blue, Night Moves, Love and Death, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, The Last Picture Show, Midnight Cowboy, The Godfather and Nashville.

Play It As It Lays finds common ground between gay male and ‘non-feminine’ female experiences of oppression

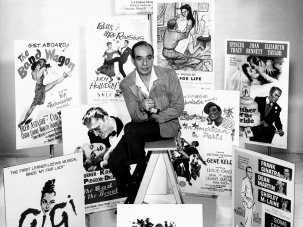

These films were my introduction to an adult world I’d barely been aware of, let alone seen tackled on screen. Though still in my mid-teens, I seem to have intuitively understood that Robert Altman, Alan J. Pakula, Arthur Penn, Martin Scorsese, Terrence Malick and Sam Peckinpah were not only radically opposed to America’s dominant trends but were developing new styles of filmmaking to express this opposition. It was several years before I grasped the debt these ‘new’ styles (particularly Francis Coppola’s) owed to European sources, and came to appreciate that Vincente Minnelli, Alfred Hitchcock and Douglas Sirk were everybit as critical of American society (and usually less complacent in their rejection of it).

What now bothers me about these films is the way in which, with a few significant exceptions, they tend to marginalise women. But I recently had the pleasure of discovering two magnificent works from the early 1970s about female protagonists (played in both cases by Tuesday Weld) attempting to assert their independence in a patriarchal society whose structures are inherently hostile to such a project: Henry Jaglom’s A Safe Place (1971) and Frank Perry’s Play It As It Lays (1972). It is surely significant that these titles fell into distribution limbo at a time when such male-centred films as Five Easy Pieces (in which Jack Nicholson demonstrates his nonconformist individuality by insulting a waitress) and American Graffiti (so uninterested in its female characters that it excludes them from a concluding summary of the protagonists’ later lives) were being hailed as masterpieces.

A Safe Place is now available as part of Columbia’s BBS box set, but Play It As It Lays remains inaccessible, aside from a few screenings on US cable channels. It doesn’t seem to have played theatrically in the UK and has never been released on video or DVD anywhere. Closely adapted from Joan Didion’s novel, the film’s achievement is in no small part due to its casting. The central characters are Maria Wyeth, an actress on the verge of cracking up, played by Tuesday Weld, and bisexual Hollywood producer B.Z., played by Anthony Perkins. After reading the book, I had difficulty imagining Perkins in this role, but he imbues it with a warmth only hinted at on the page.

Whether consciously or not, Perry’s casting decisions seem to have been influenced by his actors’ private lives: Weld might easily have served as the model for Didion’s protagonist (as she later did for a character in Robert Stone’s Children of Light) while, as far as I’m aware, this is the only time the bisexual Perkins was permitted overtly to express his real sexual identity onscreen.

The main concern of the film (though not, I think, the novel) is the way in which the gay male (B.Z. wears feminine cut-off shorts at several points) and the female who resists pressure to behave in an appropriately ‘feminine’ manner (Maria wears jeans or trousers in all but two scenes) form a relationship whose relaxed intimacy is based on a shared experience of oppression – an intimacy Weld and Perkins convey with an apparently effortless ease that may be a consequence of their having already acted together in Noel Black’s Pretty Poison (1968). It has to be admitted that some of the supporting performances are relatively inert: Adam Roarke, for example, is adequate as Maria’s filmmaker husband but lacks the authenticity of the two leads; casting a genuine director such as John Cassavetes or Dennis Hopper in this part might have taken the film onto a whole other level.

But it would be foolish to quibble about a work whose flaws are part of its appeal, leaving it helplessly adrift amidst mainstream American cinema’s more ‘professionally’ manufactured output. We are only just beginning to gain enough hindsight to evaluate this unquestionably remarkable period of filmmaking: if Play It As It Lays were more widely known, it would surely be regarded as a key title in the history of New American Cinema.

-

Sight & Sound: the November 2012 issue

The best of Venice, Toronto and the upcoming London film festivals: Sightseers, Rust and Bone, Ginger and Rosa and On the Road.